Continuing the Conversation: Politics of Material Memory

February 1, 2018

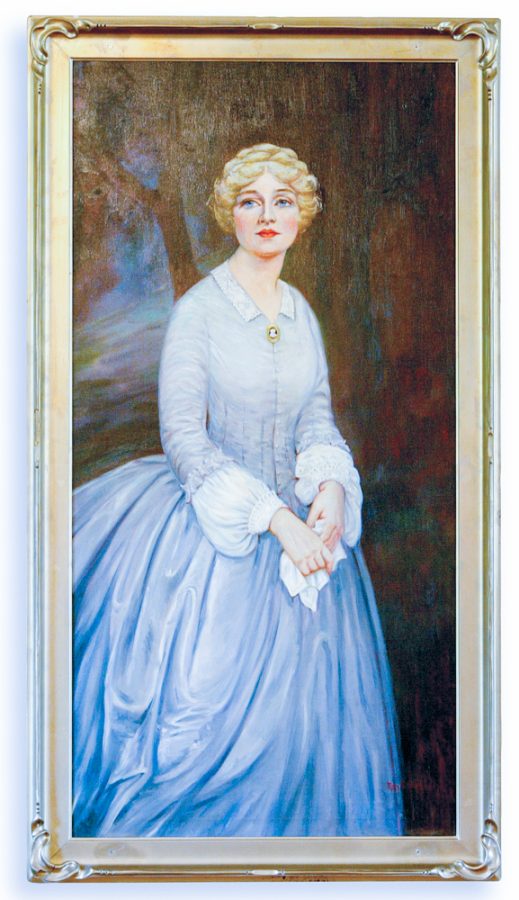

On October 9, 2017, recognized nationally as Columbus Day and unofficially as Indigenous People’s day, the portrait of Narcissa Whitman hanging in the Great Hall of Prentiss was defaced and the hands on the statue of Marcus Whitman were painted red. This past Friday, students, faculty and staff gathered at a “Continuing the Conversation” event to discuss how this act has sparked change in the community.

Professors Libby Miller, of the Art History and Visual Culture department, and Stan Thayne, of the Anthropology department, facilitated the discussion of the defacement under the broader lens of “The Politics of Material Memory.” They examined how our use of memorials can reflect the current political climate. Miller emphasized the importance of how we choose to physically represent our history, exemplified by our treatment of art featuring the Whitmans.

“The ways in which we narrate history and the objects that we choose to narrate that history … often says more about where we are in the present than it does about those past moments that we’re talking about,” Miller said.

Photo by Tywen Kelly

Students and other community members present on Friday discussed the incidents with the Whitman art in the broader context of political protest using art. Thayne brought up an example involving a statue of a controversial political figure in Martinique: Empress Josephine. The statue was beheaded and painted as an act of protest, but no attempts to repair or clean the statue were made by any officials. The anticolonial sentiment behind the beheading of Josephine shows parallels with the defacement of Narcissa/Marcus, but the response at Whitman shows a sharp contrast to the response in Martinique. Whitman staff removed and cleaned the painting and statue immediately following the incident on Columbus Day, keeping the act of protest out of the public eye.

Senior Zuhra Amini felt that keeping the paint on the portrait would have proven beneficial for future discussion of the Whitmans’ position in history.

“For me, it would have been more rich to see the tension between the spray paint and the painting because it opens up dialogue about the relationship between history (Narcissa’s) and response (the person who defaced her),” Amini said. “It frustrates me that the college would spend more money to restore a painting that became more dynamic and complicated after the defacement.”

Prior to the incident on Oct. 9, students were making their feelings about the art featuring the Whitmans known. The housing office received complaints from various student groups about the portrait of Narcissa over the years, but did not inform the members of the Art Advisory Committee, so no action was taken to remove the painting until the defacement.

Kynde Kiefel, Collections Manager for the Sheehan Gallery, along with Daniel Forbes, Director of the Sheehan Gallery, manages almost 3,000 works on campus including the art featuring the Whitmans. Kiefel mentioned her disappointment that the complaints were not made known to her and other members of the Art Advisory Committee sooner.

“After all of this, understanding that there were multiple complaints, it makes me sad that we didn’t know about that,” Kiefel said. “[Narcissa likely] would have just been put in some hanging files until further notice.”

Going forward, Kiefel wants to maintain a proactive and open approach to examining the art located on campus, with a focus on collaborating with interested students on campus. “Any student group that is interested in having this conversation, I am very interested in talking to them,” Kiefel said.

Currently, the portrait of Narcissa has been relegated to storage until further discussion and a decision from administration. The removal of this controversial piece, even for the time being, falls into a pattern of relocation involving art featuring the Whitmans.

Kiefel described a piece titled “The Whitman Legend,” that hung outside the President’s office until recently. When Kiefel and Forbes took the piece down for cleaning, they decided it shouldn’t be returned to a place of such prominence for the institution and it was placed in a classroom in Maxey.

Photo by Tywen Kelly

“We feel a need and an obligation to make sure our objects are treated thoughtfully … and placed where they can perhaps be dissected, but not dictate something as far as the identity of the college,” Kiefel said.

During the discussion on Friday, Miller pointed out that the defacement of Narcissa brings to light a serious question about the ways we represent the troubled beginnings of our institution.

“Moving forward, what should Whitman be doing? How might we want to think about the material remnants or memorials or monuments to Marcus and Narcissa at Whitman?” Miller said. “I think that is a conversation that we need to be having.”

Cassandra Otero, participant in the discussion last Friday, thinks the critique of the art featuring the Whitmans is only the beginning to a long process of repairing the school’s core identity.

“It is important to examine the artifacts which explicitly celebrate the colonial history of this institution. At the same time, we must acknowledge that the institution’s very existence is an act of colonial violence. The buildings on campus honor the legacy of the Whitmans and the college itself occupies the land of the Walla Walla, Cayuse and Umatilla. These tribes were forcefully displaced in the name of manifest destiny,” Otero said in an email to The Wire. “In short, the college benefits from and perpetuates white supremacy.”