The role of salmon in the Pacific Northwest cannot be understated. They are a keystone species in both coastal and inland ecological systems and they generate billions in economic activity through recreational fishing. To the Indigenous tribes of the region, salmon are a vital part of spiritual and cultural identity.

“Salmon hold a sacred place in the heart of our community,” sophomore Lindsey Pasena-Littlesky, a member of the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation (CTUIR) youth council, said. “[Their] importance transcends mere sustenance.”

She described the creation story she grew up with, in which humans were brought to Earth by the Creator. The Creator asked if any of the animals and roots would sacrifice themselves to feed the humans.

“Salmon were the first to offer their bodies, and other animals and roots soon followed,” Pasena-Littlesky said.

These species became known as the “first foods,” and are honored for the sacrifice they made to humans.

Salmon sustained tribes of the Pacific Northwest for thousands of years. Prior to colonization, an estimated 10 to 16 million salmon passed through the Columbia River Basin annually. However, commercial overfishing by European settlers caused a significant decline in salmon populations. The 23 Columbia Basin dams built between 1889 and 1920 only furthered the decimation of historical salmon runs.

The United States Constitution states that treaties are “the supreme law of the land,” yet today, tribal fishing is severely limited due to dwindling salmon populations. Pasena-Littlesky became passionate about salmon conservation at a young age after seeing how her family and community were not able to fish for salmon on their ancestral lands.

“We [tribal youth] understood that climate change was already taking a toll on our waters, but we soon learned that the hydropower system, primarily the dams, was having profoundly detrimental effects on the rivers, causing a decline in the salmon population,” she said.

“[The Snake River salmon] have experienced some of the most substantial declines,” junior Henry Roller said.

Roller became involved in Snake River activism in 2020. Since then, he has planned rallies and marches in Seattle and Olympia, as well as informational sessions and postcard writing events on campus.

“[Prior to colonization] the annual historical sockeye return to Idaho’s high mountain lakes via the Snake River was 100,000 plus, and this year we had 31,” Roller said.

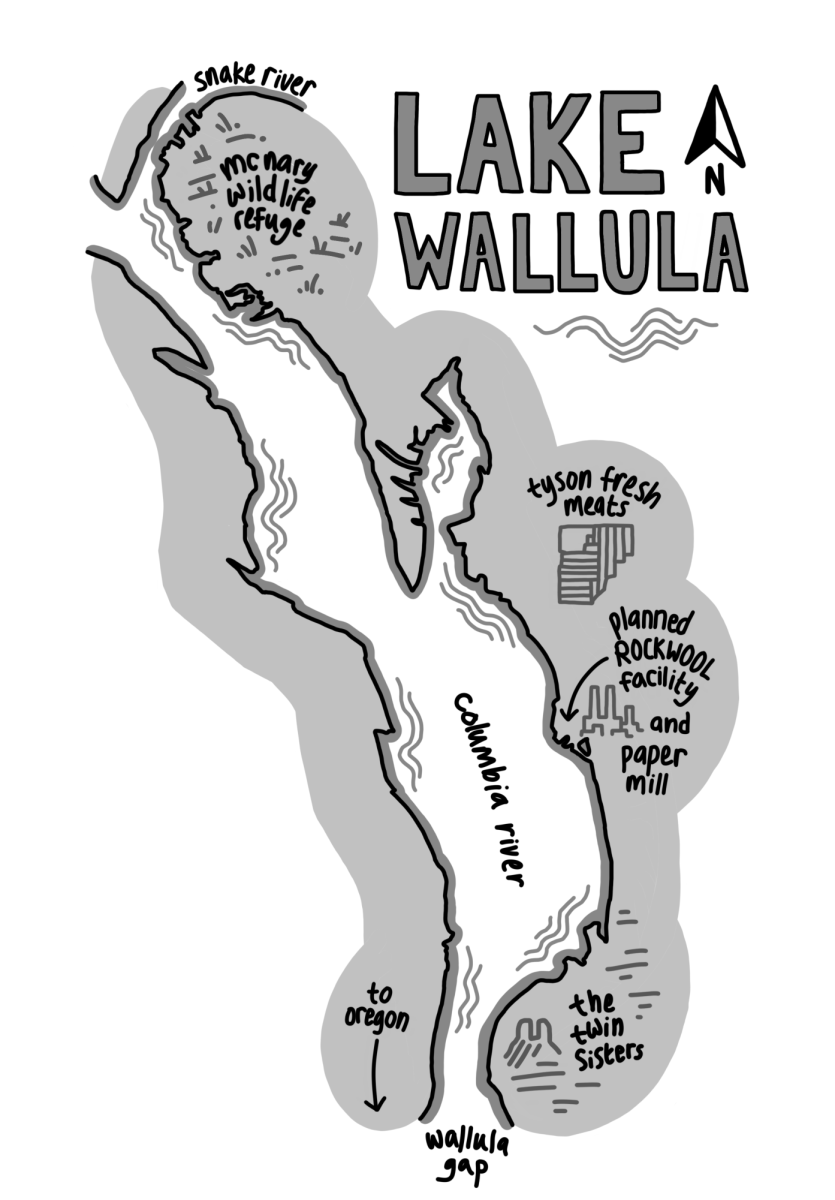

From the beginning, state fishery agencies knew the Snake River dams would have detrimental effects on salmon. However, they reluctantly agreed to the four dams, which they determined were better than the six to 10 dams proposed for the Lower Snake. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ Walla Walla District completed the Ice Harbor dam in 1962, which was followed by Lower Monumental, Little Goose and finally Lower Granite, which was completed in 1975.

Since the dams’ construction, there have been numerous agreements, reviews, action plans, initiatives and orders put forth by various groups with the aim of recovering Snake River salmon populations. In fact, government agencies have spent more than 17 billion dollars (adjusted for inflation) on Snake River salmon recovery in the last 40 years, yet the effects on wild salmon have been negligible.

Last month, President Biden released a memorandum aimed at restoring healthy wild salmon populations to the Columbia River Basin. The memorandum specifically acknowledges the work being done by tribes to restore salmon and the importance of protecting tribal fishing rights.

“This memorandum serves as a symbolic signal for industries to recognize the harm they may be inflicting on the natural ecosystem,” Pasena-Littlesky said. “[It] provides a platform for us [Indigenous people] to educate society on the principles of coexistence and how they can be applied to restore our natural ecosystem.”

Roller was also encouraged by the memorandum.

“It directs federal agencies that are relevant to this issue to take the actions necessary to recover salmon throughout the Columbia Basin,” he said.

However, he noted that Bonneville Power Administration (BPA), who markets and distributes the power generated by the Snake River dams, will likely propose improved fish ladders or other dam workarounds rather than breaching.

“BPA likes to drag their feet. They’re probably not going to have a great response,” Roller said.

Assistant Professor of Anthropology and Religion Stan Thayne had a somewhat pessimistic outlook on Biden’s memorandum.

“It just reiterates things that are kind of already there,” Thayne said.

Thayne pointed out that the statement never specifically mentions dam breaching. He argues that most statements released by government offices are crafted to seem like they support breaching, without making any sort of firm commitment.

The Snake River salmon don’t have much time to wait. The Nez Perce Tribe Department of Fisheries Resource Management predicted that more than three-quarters of wild Chinook populations in the Snake River will be functionally extinct by 2025 without dam removal.

“If these dams stay in place much longer it’s going to be too late,” Roller said.

So why does breaching continue to be put off? Roller argues that a lack of political will is the biggest barrier to removing the Snake River dams. He identifies irrigation, energy and transportation of grain as the biggest benefits provided by the dams that people are afraid to lose.

“All the services they provide can be replaced and the salmon can’t be replaced,” Roller said.

In addition to economic concerns regarding the breaching of the Lower Snake River dams, Thayne acknowledges the fear of some that if these four dams are breached, it is only a matter of time before other dams become targets. These notions aren’t entirely unfounded.

“There are plenty of other dams that are very problematic,” Thayne said.

However, the Snake River is uniquely positioned as a target of environmental activism for multiple reasons. First, the amount of energy produced by the four dams is much easier to replace than other dams in the Northwest.

“[Washington’s] Grand Coulee dam alone produces about 2.5 times more [electricity] than all four Snake River dams combined,” Roller said.

Only about 5% of hydroelectricity sold by Bonneville Power comes from the Lower Snake River dams.

Additionally, the segment of the river behind the Snake River dams that meanders up into the mountains of Idaho provides critical cold water for salmon.

“[Behind the dams] is 5,000 miles of high quality salmon habitat,” Roller said.

As climate change continues to warm rivers and streams to temperatures that may soon be inhospitable to salmon, this cold water mountain habitat is crucial for Northwest salmon’s future survival.

Snake River salmon still have an uphill battle toward recovery, but they also have numerous dedicated supporters who will not let these essential populations die off without a fight. Roller has been heavily involved with numerous activist groups, including the Youth Salmon Protectors, an Idaho-based coalition of young people advocating for Lower Snake River dam removal.

“[Youth Salmon Protectors] are very effective, very well organized and very motivated,” Roller said.

However, he gives the tribes the majority of the credit.

“They have been extremely dedicated and very, I think, effective,” Roller said.

Indigenous tribes around the Northwest have been working to restore damaged habitat and revitalize salmon populations for generations.

“Our relationship with the salmon is rooted in tradition and we, as the youth, are dedicated to preserving and protecting our rivers and salmon because our ancestors made a promise to our Creator, a promise we must continue to uphold,” said Pasena-Littlesky.

She explained how humans were endowed with the gift of speech by the Creator.

“It is this voice that we now use to protect those beings who have protected us for generations,” she said. “The salmon’s life cycle is a sacred promise with our people and it is our duty to safeguard our rivers so that the salmon can continue to return to the lands of our ancestors.”