A Proper Monument? Narcissa Whitman Exhibit

April 19, 2018

Avisual exploration of the discourse surrounding the Whitman family makes its home in Maxey Museum’s newest exhibit, “A Proper Monument?”, which opened on April 11 and will remain up until May 5.

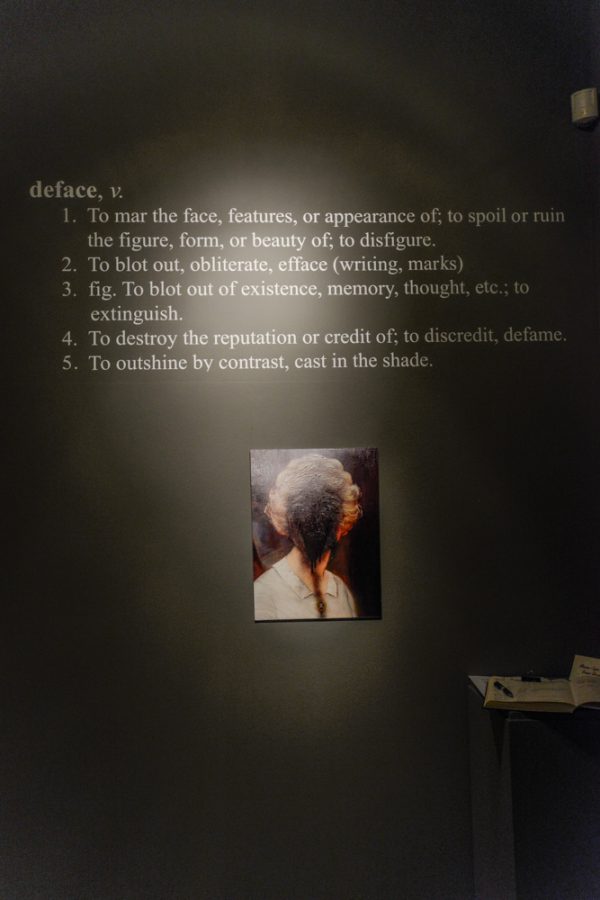

The exhibit features a wall-mounted timeline of the Whitmans and the monuments that they left behind, beginning with the establishment of the Whitman Mission in 1863 and ending with the vandalism of the Marcus Whitman statue and Narcissa Whitman painting in 2017. Various historical artifacts accompany the timeline. The exhibit also includes a section on colonial monuments in post-colonial Africa, a section on Whitman monuments around the United States, a reflection on the stories surrounding the Whitmans and the original portrait of Narcissa Whitman, now turned upside-down, along with a lock of her hair.

The exhibit was created after the defacement of the statue and painting. Professor of Anthropology and Religion Stan Thayne, who was one of the curators, believes the exhibit is an important addition to the current conversations occurring on campus about the Whitmans.

“Those … interventions that took place … are just kind of crying out for a response,” Thayne said. “And I think a lot of students on campus wanted to know how to think about this, how to respond to it. Some people were troubled by the institution’s response to it, and I found a lot of students just didn’t seem to know what they thought of it. So it seemed like a great opportunity to have this conversation, that was already underway, but maybe not to the degree it merits.”

Professor of Art History and Maxey Museum Curator Libby Miller agreed that the exhibit is important to have now because of its timeliness in response to the defacements, as well as the greater national focus on monuments.

“In the same way that someone spray painting a monument or doing something to it makes it become noticeable, this discourse in our more general public sphere on a national level, and not just on a local level, makes monuments suddenly visible in a way they weren’t before,” Miller said. “We see the Marcus Whitman statue more now that confederate monuments have been taken down.”

Miller expanded why it is interesting to look at the Whitmans’ monuments.

“Monuments…lend stability to historical ideas that are by their very nature unstable,” Miller said. “It’s almost because the ways we attribute meanings to history are so unstable that we need monuments to create an aura of stability around them.”

The ways in which the exhibit examines these monuments range in style and scope. Student curator Aidan Nuttall ‘19 examined the different monuments to the Whitmans around the country, creating a map of the U.S. with corresponding photos and quotes discussing monuments in various regions.

“I think that we are in a pretty unique geographic location for the Whitmans in that we come into contact every single day with the Whitman name as well as representations of the Whitmans, just because we live here, we eat here, we go to school here,” Nuttall said. “I was interested in how places where the Whitman legacy is confined to an elementary school or in some cases as little as an engraved rock…interact with the Whitman legacy.”

Another student curator, Spencer Christian ‘20, hung a mirror in the space, challenging viewers to critique the stories told about the Whitmans.

Equally interesting is Narcissa Whitman’s hair on display. Kynde Kiefel, Exhibitions and Collections Manager for the the director of the Sheehan Gallery, reflected on the meaning behind it, as it was delivered to President Polk along with the news of the “Whitman Massacre.”

“[Narcissa’s hair] was sort of weaponized…we infuse objects with life as soon as we talk about [them],” Kiefel said.

Student curator Eli Cohen ‘19 created a slideshow focusing on other places in the world including Namibia, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Kenya, and how those countries deal with objects from their colonial past.

“I was looking at how different aspects of each of those, like the defacement, the history of the settlers in that area, and the different aspects of all three of those countries can inform us about different aspects of the Whitmans’ legacy here in Walla Walla,” Cohen said.

Lisa Uddin, Professor of Art History & Visual Culture Studies, described the benefits of grappling with the question of the Whitmans through the medium of the museum space.

“You get the authority of the museum space, which does a lot of work to legitimate the conversation…It is a space of institutional visibility and community visibility,” Uddin said.

Although the exhibit offers many different angles to consider the Whitmans from, it is not necessarily there to provide answers.

“I always hope that people come away with more questions than answers and that it complicates whatever you think coming in,” Miller said.

Uddin also hopes that the exhibit is not the end of the conversations about the Whitmans on campus.

“I think there is a kind of momentum for the conversation, and I don’t want people to forget,” said Uddin. “My hope is that we can continue…to keep asking about “Where are we?” and “How did we get here?” You need historical markers for that, but they’re not neutral, and we need to talk about that.”