Divestment: An Economic Perspective

November 9, 2018

During the height of the U.S. anti-apartheid movement in the 1980s, college students all across the nation protested university investment in companies that traded with or owned operations in South Africa. Due to increasing pressure from these students, many institutions divested from these companies independent of any regulations sanctioned by the federal government. This rise in divestment, motivated by young, passionate protestors, combined with the many outcries of American citizens, eventually led to nationwide, federally enforced divestment. Young people had helped change the world, but of the many that did aid the movement, one university that never chose to divest was Whitman College.

Since the 1980s, new systems have been put in place to make it easier for students at Whitman to appeal for financial divestment from morally unjust organizations. In order for Whitman’s Board of Trustees to consider divestment there must be a proposal submitted that explains exactly why this specific divestment should occur. The ultimate goal of this proposal is to prove to the Board that the effects of monetary investment in this resource, industry, etc., are what they could consider to be “conscience shocking,” an admittedly vaguely worded subjective approach to the idea of financial divestment.

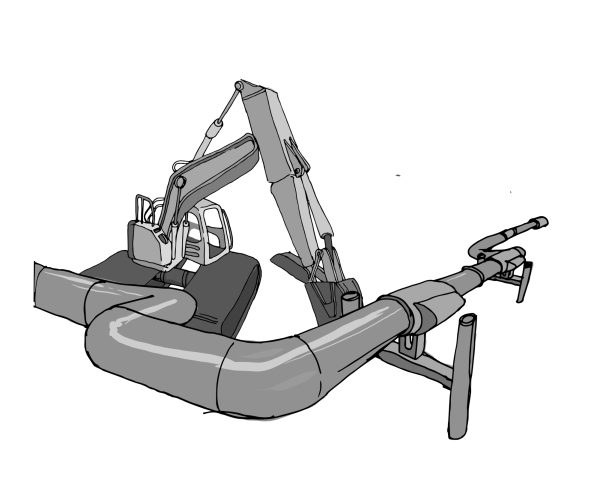

The “Divest” movement has also changed since the 1980s; where Whitman alumni once camped out to protest South Africa, current students now protest environmental destruction by the fossil fuel industries. Their goal is to urge Whitman to lead the new movement, the movement against the anthropogenic warming of our climate, starting with divestment from the coal industry. They construct their protests and the divestment proposal on a foundation of facts and objective reasoning, as well as an understanding of the human costs of climate change. But when these facts aren’t enough, when the Board won’t react to years of devastating climate change, environmental racism and classism enacted by our government, and the continual gradual degradation of our environment, Whitman students must instead … shock the Board’s collective conscience?

Personally, I’m frustrated that the Board won’t engage in the fight against an immoral system that hurts all communities, both human and non-human, and especially the most marginalized in our society. But from an economics perspective, the Board could actually consider the science of climate change objectively, especially because divestment from anything is a financial matter and does not necessarily have to be an ethics-based decision. Objectively, coal industries are declining – according to a 2017 policy brief from the Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research, this is not due to environmental regulation by the government, but instead rapid replacement with natural gas and other, more environmentally sustainable energy sources. In short, the coal industry is becoming less profitable every year, and ultimately the less money Whitman makes, the less financial aid it can offer.

Maybe your conscience isn’t shocked by the detrimental medical effects of coal on communities, by the pillaging of the Earth, or by the deaths already resulting from freak weather patterns and the injustices perpetrated by fossil fuel industry. But if we follow the Board’s example, this issue isn’t really about shocking the conscience or they would have already divested. This is about money, and if the problem needs to be dehumanized for the Board to fully address it, then we as students can come to understand the real privilege of our trustees: that they are morally willing to reduce a complex decision currently affecting human lives into an argument about monetary investment in an industry that is already on its way out.