The Pursuit of Authenticity

October 4, 2017

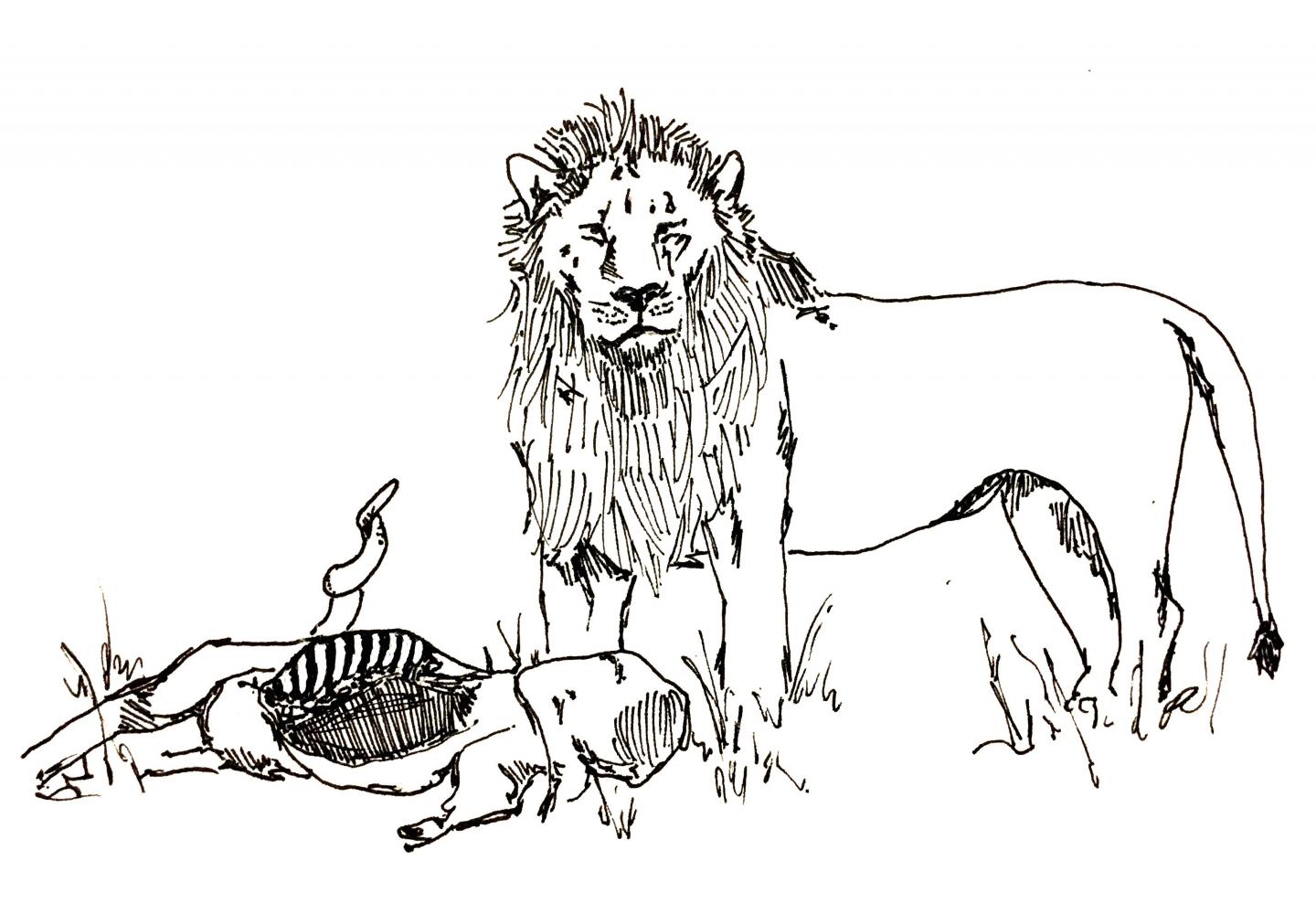

We humans crave the anxieties of the Savanna. To engage in a standoff with a hungry lion over an antelope carcass is a dream many of us secretly harbor. The rush of leading a life on the edge, where only the essentials matter, is shared almost universally by those who play boardgames, watch TV shows and engage in extreme sports. Replace the antelope with a digital recreation, a little red flag or the words “you win,” and the desire becomes apparent. Once you’ve started paying attention, the craving begins to pop up everywhere: it appears in pharmaceutical commercials, where an anxiety is induced and then relieved; it pops up in video games, where monsters must be defeated in order to achieve a gold star; and it even shows up in academics, where a test begins to take on the form of a ravenous carnivore.

In the short term, these surrogate activities appear to give our lives meaning, but over time their power begins to decline. Sooner or later, we find that in order to really be fulfilled, our activities should serve an essential purpose. These essential purposes are diverse, but they all relate in some way to our basic needs: food, water, shelter, sanitation, healthcare. The problem, of course, is that none of the activities that lead to these needs are direct enough. In order to acquire food, we must sit in front of a computer screen for a set amount of time; in order to acquire healthcare, we need to vote properly in an election that happens every four years; and in order to have proper sanitation, we need to pay taxes.

This sort of indirectness would seem inconsequential were it not for the ubiquity of surrogate activities; we sit in houses bought with funds acquired from office work playing video games that simulate building houses. There’s clearly something slightly off about this, especially when the surrogate activities involve closing oneself off to the world. It’s actually an interesting aside—discussed perhaps by figures like Durkheim—that as social cooperation becomes the norm, people begin to feel more and more alienated from one another, ultimately retreating into solitary surrogate activities.

The alternative, of course, is equally problematic. If living an authentic life means building my own house, growing my own food and managing my own sanitation, does that leave any room for social cooperation? Further, how am I to engage in creative pursuits if I’m constantly tied down by my self-imposed obligations? The answer here really should be simple: Try to live an authentic life within reasonable boundaries. Just as retreating into surrogate activities can be unhealthy, completely retreating into authentic activities can be. The goal really should be to find a healthy mean between the two, where social cooperation is maintained but the fruits of one’s labor are clear.