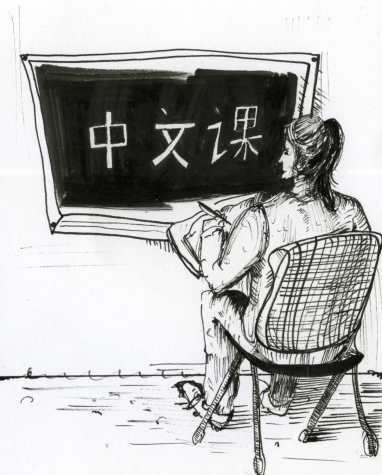

Learning in another Language

February 9, 2017

Seeing that Whitman has a cultural pluralism/language requirement and many students do in fact speak one or more languages other than their first language, I thought it would be interesting to give another perspective on how to think differently on the importance of languages not just intellectually, but also emotionally or psychologically. As a multilingual, I always wondered what it meant to know other languages. I often tell my friends in college that they don’t really know ‘the real me’ because I feel like a ‘different’ person in English. I only feel at my best when I speak and interact in my Native language and this is not related to fluency or vocabulary. People usually think that if they learn grammar perfectly and learn as much vocabulary as possible, the closer they are to mastering the language.

Is it enough to know the vocabulary and grammar and have fluency? Would the mission be accomplished after a couple of years of a certain number of classes per week and very hard work in learning the written and spoken aspects of the language? And would for example, a trip to Spain or Mexico finalize all your efforts and crown you as a legitimate speaker of the language?

There is no doubt that to learn how to speak a language properly you have to learn its structure and vocabulary, but this is not what gives beauty and uniqueness to a language. To really know another language, you have to immerse yourself and understand the culture associated with it. People often underestimate how languages have the power to convey important insights about the country they are spoken in and the people of the country.

A language’s idioms, phrases, jokes, daily slangs or even the voice tone that is used for each of them, has told me a lot about the people who speak it as their first language. I have learned something of the values their culture holds as important and what kind of perspective they have on daily interactions and personal relationships. I have learned about the way these interactions differ : what kind of vocabulary is used when talking with their parents or their friends. You start to notice differences with your own language and even reflect on what it can say about your society and your culture. You might even start wondering why in English the phrase ‘I love you’ is a standard phrase that you use to express this feeling towards anyone, while in another language there are different ways to say ‘I love you’ depending on the person you want to say it to.

A language is a feeling. Unless you ‘understand’ this feeling, you can’t really know the language. There is a reason why you should roll your Rs in Spanish or prolong the last syllable in Italian. There is a reason why they say French is the language of love or why German is considered to be such a strong language. Languages become an emotional experience and a journey that enriches the heart as much as the mind. Eventually, we become different people in different language that we speak. There have been studies made by psychologists, which provide evidence to this claim. We embody ‘different personalities’ and act differently as well. Even our voices change and we have no control over that. We find our new place in that language, we start thinking in it and eventually words come out of our mouths easier. Our brains don’t translate from our first language to the other one. Everytime we have to speak in another language, it is like we put on new clothes. And sometimes these clothes really fit us well.