Language learning, language loss

October 27, 2022

“Am I allowed to swear in this interview?” asked first-year Aubrey Nickle. My finger hovered over the voice memo record button.

Regardless of my answer, she continued buzzing around her room, blurting German phrases and answering questions — all while folding her laundry. As a German heritage speaker, Nickle perfectly demonstrates the findings of a 2012 study where the National Institute of Health concluded that bilingual individuals are more able to focus and multitask in distracting environments. Unintentionally, Nickle’s interview setting became a real world example of these findings.

A heritage speaker refers to somebody who has learned a second language in an informal setting, such as within their family. The number of heritage speakers in Washington State alone tripled between the years 1980 and 2010, speaking to the modern trends in globalization. As technology further connects the world, we’ve seen an uptick in multilingual backgrounds. However, the way that heritage speakers learn language stands in stark contrast to the language instruction that students experience at Whitman.

An anonymous first-year Japanese heritage speaker explained to me how he learned the language.

“My mom spoke to [my younger brother and me] in Japanese, so I picked up on it. My mom’s not a great English speaker, so we mostly speak Japanese when we’re together.”

Despite growing up in a Japanese household and being able to use conversational Japanese with his family, the anonymous student is currently enrolled in an introductory Japanese class at Whitman, which he hopes will help him read and write in Japanese.

While he’s still learning, the anonymous student explained the difficulties he’s had in maintaining his Japanese.

“The older I’ve gotten, the less and less Japanese I use. It has kind of fallen off for me, but I definitely try to keep it up.”

Language classes are more than a potential cultural pluralism credit: they offer students an opportunity to reconnect with their heritage in the absence of family. Still, it’s not always easy to connect to non-English languages, as English is widely considered the world’s “most powerful” language. Even outside of English-speaking countries, English proficiency is often a gateway to business and higher education. This poses a particular problem for heritage speakers: the higher someone climbs on the socioeconomic ladder, the greater the alienation they may experience from their language and ancestry.

Nickle experienced this exact phenomenon, beginning at a young age.

“I actually spoke German first before English,” Nickle said, still folding her laundry. “Once I started going to American schools, I just lost it.”

While Nickel is a heritage speaker, language loss has disrupted this heritage. Nickle still has family in Germany today and explained the shame she often feels in their presence, especially when they asked if she could speak German.

“When I said no to them, I felt embarrassed, like I should be able to,” Nickle said.

Nickle isn’t alone in this embarrassment. It’s a common theme, even for her mother. Her mother speaks German fluently, but she struggles with grammatical rules.

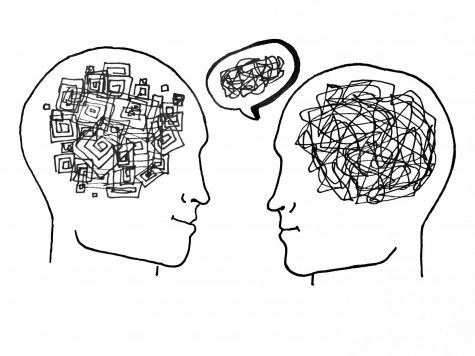

Most language experts would agree that immersion is the best language learning method. Classroom instruction, despite its shortcomings, is the next best thing. However, sometimes the formalization of language can trigger confusion in heritage speakers: many begin to wonder if they’re speaking their own languages “correctly.”

We can credit Nickle’s feelings of shame and fraudulence partially to a form of bilingual-specific imposter syndrome. Imposter syndrome refers to a psychological phenomenon where one feels like an “imposter” in their own body, as if the accomplishments that they’ve made aren’t really theirs.

For bilingual individuals and heritage speakers, imposter syndrome can manifest in several ways. A common one is the feeling of unworthiness in claiming one’s ancestral identity. Nickle expressed the frustration she feels towards her imperfect grades in German class.

“Even if I do okay on a quiz, I feel like I should’ve done better — it just gives me this embarrassment,” Nickle said. “I feel like I can’t fail, like there’s no excuse for this.”

The anonymous first-year student has begun to feel less pressure about being the “perfect” language speaker. He sees his Japanese family regularly, giving him ample opportunity to speak Japanese in a casual setting.

An emphasis on this casual speaking seems to be important. Kristine Valencia is a visiting student and Spanish heritage speaker who didn’t learn Spanish until later in life. She agreed with this sentiment.

“I grew up with an American foster family, so I didn’t speak any Spanish,” Valencia said. “After a while of watching shows and listening to [Spanish] music, I started to build the foundation.”

This informal approach is sometimes the best that heritage speakers can achieve when life gets in the way of family and passing on languages. Heritage speakers’ immigrant parents must often contend with sets of financial and social barriers. Nickle explained some of the factors that stopped her from continuing to learn German.

“[During my childhood], my mom worked at a job that treated her really badly, and that was a pretty low point in her life. I think she probably didn’t think about teaching me German,” Nickle said.

The complications of linguistic and grammatical rules can complicate the process of learning language in a formalized setting. An even greater issue may be seen in the lack of representation for languages with a historically smaller population of speakers, such as Indigenous languages and languages simply not recognized from a Western perspective, like various African dialects.

As language classes can become such an important tool for heritage speakers to continue learning and practicing their language, I believe it’s appropriate to ask more of Whitman’s language curriculum to reflect the school’s student body. The decisions of curriculum, after all, are decisions of whose presence we acknowledge and celebrate in this world, the priority being the students who temporarily call Walla Walla home.