Op-Ed: What Whitties should know about Standing Rock

November 17, 2016

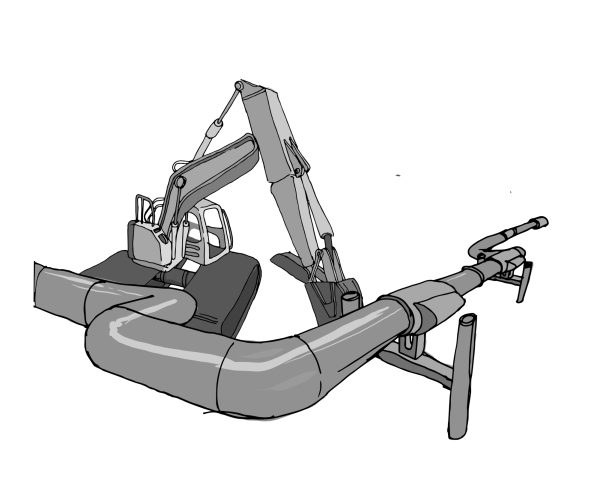

Last week, five Whitman students loaded our pepper spray goggles, canned beans and sleeping bags into a car and drove 17 hours to Cannonball, North Dakota to join water protectors there in halting the construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline. Here are some things I learned:

1. This issue is first and foremost about indigenous sovereignty. We cannot engage with Standing Rock only to the extent that it aligns with our own environmental, human rights or anti-corporation goals. We must recognize indigenous sovereignty as worthy in and of itself.

2. Colonization is not in the past. It is strong and alive in the construction of this pipeline. We witnessed 24-hour helicopter and drone surveillance of camp life and sacred ceremonies. We saw the effects of police raids on peaceful camps. We saw DAPL workers constructing all night on stolen native land, and the National Guard putting up razor wire on the banks of the Cannonball River to stop native people from praying there. If you are enraged by previous acts of colonial violence, now is the time to act.

3. Every action at Standing Rock is rooted in prayer, ceremony and spirituality. We attended more ceremonies than rallies, said more prayers than chants and took our direction from elders, not activists. I found myself secularizing the movement by explaining its methods in terms of “strategy” instead of spirituality. What I was really doing was legitimizing action only to the extent it aligned with my colonial values of rationality and tactics. In reality, Standing Rock’s guiding principle is a prophecy from the Spirits: “If you remain peaceful and prayerful, you will win.”

4. The difference between protesters and water protectors is not just a technicality. It is a fundamental distinction. “Protester” describes a group of people who only mobilize as a group in opposition to something. “Protector” acknowledges that our human unity runs far deeper than any government action. Protectors are not fighting for a concept: we know that water is sacred. Protectors are enacting our duty to physically defend that water.

5. Contrary to the framework used by many non-native environmental organizations, this movement is not about “protecting natural resources.” Indigenous knowledge holds that water, land and animals are not valuable only in terms of their usefulness to humans. They are not our resources, but our relatives.

6. Showing up to a march, a teach-in or even to North Dakota with good intentions is not enough. How you engage in allyship is as important as showing up itself. At the camps, we witnessed non-native people offering suggestions for action before listening to the plans of native organizers, taking songs from sacred ceremony to use in their own lives without permission and showing up with little understanding of their position as guests on Lakota land. Some of these mistakes were made by us. It became clear that self-reflection, awareness of the space you take up and intentional action are vital to allyship.

Since Tuesday’s election, there is a very real, rational and visceral fear in our collective body. However, indigenous lives, culture and land have been trampled on under every form of American government. To many native people, this kind of justice is neither surprising nor anomalous. This should not instill fear or doubt in us, but hope: a bigger vision for unity and action is needed. I will be taking my direction from the protectors at Standing Rock, whose action runs deeper and longer than the next four years, much like the powerful flow of the Missouri River.