Struggles in STEM

October 27, 2016

Whitman faculty members are becoming increasingly concerned that the playing field is not level for all of the college’s students.

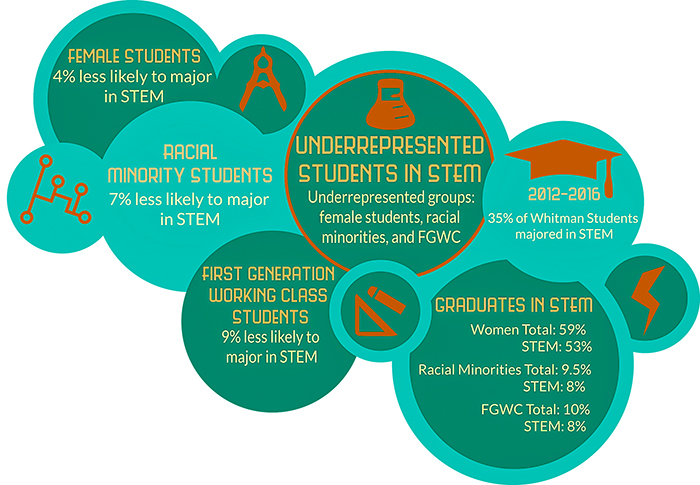

At Whitman, a large number STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Math) graduates are white, male and have college-educated parents. Most colleges across the United States also struggle with higher attrition and lower graduation rates of students from underrepresented groups in STEM. While universities and organizations like the National Science Foundation differ in their exact definitions of students from underrepresented groups, all of them agree that students who have historically faced barriers to success including females, racial minorities and first generation working class (FGWC) students.

Statistically speaking, Whitman has reason to be concerned about all these groups of students.

Between 2012-2016, 35 percent of the general Whitman student population majored in a STEM field. Compared with the general population, female students were 4 percent less likely to major in STEM, racial minority students were 7 percent less likely and FGWC students were 9 percent less likely.

Though Whitman’s graduation rate for students from underrepresented groups in STEM majors is near the national college and university average, many faculty members and administrators are still concerned. Whether underrepresented students are choosing not to continue or if they completely avoid STEM majors, many around the college believe it is because they lack the proper support. What is Whitman doing to change this?

Cultivating Confidence

The STEM majors offer a variety of support systems for students who need additional help outside of class. However, students from these backgrounds often lack the confidence to utilize them. Some STEM professors recognized that being a minority within a classroom setting can make some students feel insecure. It becomes difficult for underrepresented groups to overcome challenges when they cannot picture themselves succeeding.

“Every student struggles at one point or another, in one place or another, but the manner in which they struggle and the way they learn from those experiences can vary quite a bit. It’s been my experience that students who don’t feel confident or comfortable…are less inclined to believe that they can overcome those hurdles,” Associate Professor of Biology Leena Knight said.

For senior chemistry major, FGWC woman of color Megan Rocha, confidence is indeed one of the key issues.

“One of the biggest challenges I’ve had to overcome was a lack of self confidence. The majority of the chemistry majors had seen chemistry before they came to college, whereas I switched schools so often in high school that even though I was certain I would be pursuing a STEM college education, I was never encouraged to take chemistry,” Rocha wrote in an email to The Whitman Wire. “I have consistently felt behind my peers and fearful that I don’t have the capacity to be competitive in my field.”

Senior Physics-Astronomy major Hallie Barker agrees that it can be difficult to have confidence when being the minority in a class. Though Barker does not feel as though she has experienced any significant challenges from being an underrepresented student in STEM, she often finds herself in male-dominated physics courses.

“I think I’ve… definitely experienced imposter syndrome before, where I think that everyone else must be smarter than me or having an easier time with the material, and feeling like I don’t belong in physics,” Barker wrote in an email to The Whitman Wire. “This isn’t because of anything that other people are doing specifically, it’s just a societal norm that physics is thought of as a male field, and it’s hard even for me to fully escape from that.”

Rocha also believes that one of the other difficulties in increasing diversity in STEM is the lack of conversations about it in the departments.

“Whitman has resources technically, but none that would ever reach a student like me. I’m a science major which takes me out of the realm of all the politically active people of color who seem to act as the voice of all of the underrepresented groups. I’m not in any politics classes, I’m not in a rhetoric class, I’m just not in the classes that actively talk about race and all of the upsetting topics that are sweeping the nation,” Rocha wrote.

College Solutions

Because many of the inequalities in STEM come from disparities in high school STEM education, Knight and others have worked to better support Walla Walla High School students studying science. During the 2012-2013 academic year, Knight worked with former Science Outreach Coordinator Mary Burt to create an evening science and math tutoring program for Walla Walla High School students in the Whitman College Hall of Science. This program has worked to help WaHi students become more confident and develop study skills.

However, Whitman is still in the process of developing programs to help bridge the gap for its own students. Over the short term, the College could give students from underrepresented groups more chances to practice difficult STEM concepts.

“The difference to level the playing field between privileged versus underprivileged is to practice…It’s all you really need to do…The only thing you really have to do is to create opportunities for students to practice that concept and…they are back at the same level,” Knight said.

Having more students available to be math and science tutors would be another way to address the issues students from underrepresented groups face. As part of the strategic planning process, Vice President for Diversity and Inclusion Kazi Joshua and Associate Dean for Faculty Development Lisa Perfetti are guiding STEM faculty through the process of creating a Quantitative Reasoning Skills (QRL) Center that would be like the Center for Speaking and Writing (COWS) in the humanities.

“We proposed that the college should establish a QRL center, so for instance, on this campus, you have COWS…but you do not have an equivalent support structure for Division III…We also think that appropriate mentoring, whether it is peer-mentoring or what not is important,” Joshua said.

Hiring more diverse faculty who can relate to the struggles that students from underrepresented groups face is also part of the strategic planning process. Joshua and Whitman’s current faculty are working together to keep the applicant pool open so faculty from diverse backgrounds can be hired.

Although the faculty have many ideas for solutions, more funding would also help them explore a variety of options. STEM faculty have been working together to apply for the Howard Hughes Grant, which would give the college dollars for that purpose.

“[The Howard Hughes Grant] is exactly what we are talking about, making sure all your programs and your networks support students who struggle,”Assistant Professor of Chemistry Nate Boland said.

One reform that may have the capacity to benefit the most underrepresented students in STEM is the restructure of STEM courses. STEM courses could be changed to meet the individual needs of the students in the class. However, this reform may be one of the most difficult to implement.

“It’s not in our 200 or 300 level classes where we see the most variation. It’s in our 100 level classes. And yet those are the classes with the most regimented structure in terms of the syllabus,” Knight said, noting that these courses are the hardest to change.

Senior chemistry major Laura Rea has felt pressures at Whitman as a female in STEM. She has been one of a handful of women in some of her upper-level chemistry courses. “I guess I felt more pressure to try harder and succeed, knowing that I was the minority, maybe subconsciously,” Rea said.

Rea also agrees that introductory courses often lose the most underrepresented students. “General chemistry really weeds a lot of people out, and I don’t know if it is based on gender, but I feel like if professors cared more about teaching gen. chem. we would have more chemistry majors,” Rea said.

Both Rocha and Barker also commented that the difficulty of some introductory level science courses is often very discouraging for underrepresented students who are struggling.

“You have to realize that people are coming in with vastly different internalized experiences that influence their perception of their own abilities, and this has a big effect on confidence performance in the intro classes,” Barker wrote. “For someone who doesn’t feel like they belong in the first place, a bad grade can confirm that suspicion, whereas it might just be a bump in the road for another student.”

Rocha also noted that these bad grades can make students feel pessimistic about their futures in STEM.

“Students who want to pursue sciences are constantly demoralized by their grades and need to be able to get through it anyway. It’s particularly discouraging when there isn’t anyone else from a similar background to discuss the challenges with. It only builds on the feeling of discomfort within the major,” Rocha wrote.

Not Stemming The Flow

While statistically speaking, students from underrepresented groups tend to struggle in STEM fields, many individuals within these groups often defy these trends.

“Statistics are a really good way of analyzing groups, but they do not apply to individuals. They are not predictors for individuals,” Boland said.

Knight agreed that these trends should not cause individual students from underrepresented groups to be discouraged from studying in the STEM field.

“Again, these are correlations. They are not absolutes. I am not saying that if you are here, you are going to be this. There is no causative relationship. It’s the likelihood,” Knight said.

Rea has noted that she actually receives special support from some of her professors who want her to succeed in STEM.

“When men tell people that they are a chemistry major people don’t acknowledge it, but when I tell people that I am a chemistry major they’re like, ‘Good for you!’” Rea said. “People are more supportive about you being a chemistry major when you are in the minority.”

However, Barker believes that professors could still do a better job of bridging the gap of support for underrepresented students.

“I think that the faculty could be [more] cognizant of the fact that people are coming in with different backgrounds and levels of encouragement that have nothing to do with actual ability or work ethic, and to be willing to provide that nudge of encouragement–that could make all the difference for someone,” Barker wrote.

Despite the school’s ongoing efforts, some students are dissatisfied with the response to the current situation.

“I’m not really sure what the college would do, but something must be done. I think a lot of people are discouraged for the same reason I was so fearful of my major–they don’t believe they can do it,” Rocha wrote.