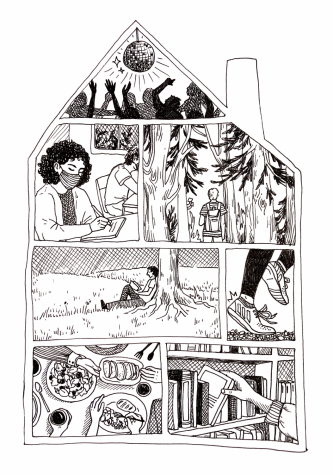

Reflections on place

September 30, 2021

I arrived at Whitman and quickly dedicated myself to the library’s quiet room. Us quiet room regulars toiled away together night after night, sharing a space but never speaking. When campus reopened last spring, I immediately signed up for a study slot, selected “Allen Reading Room – Tables” as my destination, swiped into the library, wiped down a chair and made a triumphant return to my favorite place. I felt a calming sense of familiarity.

Now that campus is fully open for the first time in over a year, sharing a place once again defines what it means to go to Whitman. Everyone steadily figures out what spaces feel comfortable or uncomfortable. I have a friend who wouldn’t be caught dead hanging out on Ankeny but can be found in the tucked-away corners of campus, by the duck pond, or that bench by the stream in front of Douglas. We’re directed to spend time in certain places, thanks to class schedules and residence hall assignments, but much of where we exist on campus is up to us. So how do we decide where we’ll be? And how do we explain our affinities for and aversions to certain places?

I think it involves multiple layers, as we consider both the physical features of an area and its purpose in our lives. For instance, senior Christian Wallace-Bailey’s favorite building on campus is Hunter Conservatory. He enjoys its aesthetics, and he has fond memories of performing with his a-cappella group there. Day-to-day, though, you can find him studying in Reid, seeking out “a very specific kind of vibe.”

“It’s so nice to be just sitting there, at like 10 p.m., staring at the sculpture being lit up as there’s like four other people in there, trying to get their work done,” he said, referring to the glass sculpture that hangs from the ceiling, within sight of certain cafe seats.

Wallace-Bailey used to prefer studying in his room—that is, until he had no other choice.

“When I went online, I could only study in my room, and so I think now I really treasure being able to study wherever I want,” he said.

He says he’s rarely in his house nowadays because of his freedom to utilize other spaces on campus.

“Especially having been here pre-Covid, I’m trying to make use of as much of the space as I can before I’m not here anymore,” he said. “Because I treasure it now … I think I didn’t treasure it the same before Covid.”

Senior Sofia Solares’s relationship to campus has also changed since COVID-19. Solares returned this fall for the first time since being sent home in March of 2020, and while she is grateful to be back, it’s “weird,” too—to feel like a stranger as an upperclassman. Especially at Whitman, a place that values community, a space is made meaningful through our relationships to the people who share it with us.

“I recognize some of the juniors, none of the first-years, and maybe some of the sophomores … I can recognize their face from being in Zoom class,” Solares said. “And when I do, it’s like, do I really recognize them? Do they remember me? Because I’ve been gone so long.”

People undeniably shape our relationship to a place. I find delight in being able to simply say hi to people when I pass them on campus—as more and more people become familiar, I feel more “at home” on campus. First-year Sonia Xu’s favorite place on campus is her residence hall’s main lounge because she can always find company there.

“I don’t really pay attention to what the place looks like; it’s more about how the people are interacting with each other,” Xu said.

There is a joy in simply being able to be in close proximity to others, especially so for Xu. She appreciates people talking in the background of wherever she studies because it makes her feel more relaxed and happy than she would be working on her own. In fact, everyone I interviewed for this article expressed a similar sentiment: they all enjoy working by themselves while around others. This sentiment is reminiscent of my fondness for the quiet room, a space in which occupants are on their own, together.

While people are important for Xu, she is also drawn toward environmental factors. In particular, she looks for sunlight.

“We are right next to Ankeny, and I feel it’s just the perfect spot for living, and it’s just really nice when the weather’s getting cold but the sunlight’s still warm and I can just spend some time lying on the grass,” she said.

Solares can also be found outside, people-watching on her hammock. Other spots that hold meaning for Solares are her house’s front porch, a space she was lacking when she lived in an apartment last year; the music building’s practice rooms, where she has spent “many, many hours;” and any kitchen—she loves to cook.

“A stove makes me feel good,” she said.

Wallace-Bailey has been thinking big-picture about his relationship to place as he prepares to leave Walla Walla, where he grew up.

“College students are somewhat transient by nature, but I, too, will leave this space soon,” he said. “And I think that is somewhat terrifying, ’cause it’s like, what does it really mean to leave Walla Walla?”

I had neither been to the West Coast nor lived in a small town before I came to Whitman. This substantial change in place shaped me: what did it mean for me to plop down in eastern Washington after growing up in Massachusetts? What does it mean for us to come from all over the world to share 117 acres’ worth of space?

We think about place as we choose to attend Whitman and as we confront the history of the land we now occupy. Even if it’s not on our minds every day, context shapes place. Wallace-Bailey notes that he is “a descendant of settler-colonialists, and [is] thinking of place in terms of who a place belongs to.”

I sometimes think of the quiet room as “my” place. I’m there often. I like its big windows and long tables. I’ve soaked up countless books and written many essays there. It has shaped me, yet it is not mine. Whitman is in several ways not “ours”: the land it stands on is not ours to claim, and we are passers-by in the history of the college. Yet, we develop profound relationships to this place, and perhaps just as meaningful as what we choose to do while we’re here, is where we do it.