All Four Years: Diversity Work at Whitman

January 25, 2018

Despite the fact that the meaning of the word “diversity” has become murky from years of imprecision and overuse, it remains firmly planted in the limelight.

At the closing senate of last semester, ASWC Diversity and Inclusion Director Megumi Rierson was given the go-ahead to develop a new diversity statement within her committee. The current statement, written and approved by the Board of Trustees in 2005, can be found on the Whitman website. Why does the old statement need a revamp?

“It just says the word diversity a bunch of times and never tries to define it,” said Rierson, who is a senior politics major. While word choice specifics have yet to be discussed, as a general goal Rierson intends to make sure student input is evident and that the statement is “by and for the people it’s supposed to empower and acknowledge.”

Since the position of Vice President of Diversity and Inclusion, currently occupied by Kazi Joshua, was created in January of 2015 as well as the formation of the WIDE (Whitman Inclusion, Diversity, and Equity) Council a month later, diversity and inclusion has been somewhat of a hot topic. ASWC and the Whitman Panhellenic Association followed suit during the 2016-17 academic year by creating Diversity and Inclusion positions of their own.

Over the 2017 Fall Alumni Weekend there was a small controversy within ASWC when a networking mixer for Whitman students and alumni of color was dubbed a “diversity event” in an email sent to student listservs. There seemed to be general consensus that the word “diversity” in that context was inapt.

“[‘Diversity’] is one of those words that we can just throw whatever meanings we want onto it and all agree on the fact that we think it’s a good idea and that it should happen,” Rierson said.

She described “diversity” as an ideograph: an abstract word with no clear affixed meaning that is used to express an undefined goal. For such a vague word, its implications are fairly complex.

The question of diversity as we know it began in the 1960s at San Francisco State. Building on the momentum of Bay Area Civil Rights groups and the larger Black Nationalist movement, the University’s Black Student Union led a strike demanding an independent Black Studies department in 1968. This was an early example of the need for a curriculum that reflected the student body.

After the concept of diversity was popularized, students and scholars began to see differences in experiences of students of color, and discussions of diversity expanded to include equity, full participation and intersectionality.

Today, “diversity” is often used to describe what scholars who study diversity, equity and inclusion refer to as compositional or representational diversity–the numerical representation of students in marginalized groups. Kazi Joshua, the college’s Vice President for Diversity and Inclusion, uses the example of simply looking at a picture of the current first-year class at Whitman. Twenty-five percent are historically underrepresented.

Joshua notes that Whitman avoids using “diversity” by itself. “We believe it is an inadequate term standing alone. It can be a shorthand for the kinds of things people are talking about.”

The word “inclusion,” he said, goes beyond compositional diversity to question of whether or not underrepresented students feel like strangers on the Whitman campus. “Equity” asks if everyone at Whitman has the same opportunity to study abroad, go on a Scramble, do research, take music lessons or participate in Greek life.

“I think Whitman as an institution … uses particular rhetoric as euphemisms for more pointed rhetoric such as racism or lack of resources that a college is providing and replace it with ‘diversity,’” rhetoric major and co-founder of the Women of Color Voices club junior Danielle Hirano said.

The pragmatic nature of the word “diversity,” however, can be used strategically.

“If we think about who is part of the institution and who is working within it, there is a lot of whiteness there. ‘Diversity’ is something that we have to use, unfortunately, because it is more palatable and it’s less abrasive in the approach that we need to address this issue of race at the college,” Hirano said.

The Whitman Experience

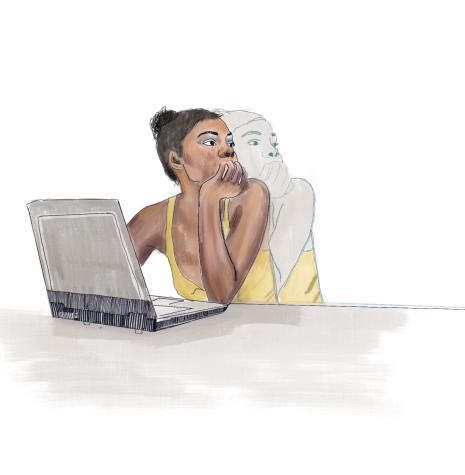

When institutions value diversity but don’t focus on equity, inclusion and empowerment, they often adopt a self-serving “add and stir approach.” This describes when people who are historically marginalized or underrepresented come to a place like Whitman and feel a kind of culture shock–they are suddenly in a world that’s not built for them.

“Whitman is really good at advertising,” Hirano said. She described how the College will use photos of students of color on the website and in brochures for marketing purposes. “I think that’s incredibly misleading,” she said. “It’s not an accurate portrayal of what you’ll come to find here.”

When Hirano took a tour of Whitman during her application process, her tour guide mentioned that Whitman has some of the happiest students, referencing a Princeton Review ranking from 2015. As an explanation, the tour guide highlighted the many resources for students including the health center, the counselling center, the climbing gym and the outdoor program.

Hirano said, “I think those standards of what it means to be happy and what it means to be comfortable in a college setting are very white-centered. It’s like, I’ve never been rock climbing before, I don’t go camping and I think there’s a lot of privilege in marketing in that way.”

When she arrived as a first-year, Hirano realized that the support for students of color was not what she thought it was going to be.

“Having a white professor teach me about intersectionality, or having white students discuss my experiences in classrooms like they are just theories and abstracts … that’s really difficult,” she said.

Tired of Talking

Joshua said that what he has consistently heard from underrepresented students at Whitman is that whatever words the College chooses when talking about diversity and inclusion, they are not translated into sufficient action.

“Now I do think that leadership is important, that diversity is important to Murray, that the Board has said this is important, going back to 2005, it’s important, that helps us. But it’s not enough for us, for the top … to say this, if the experiences of folks down on the ground are not consistent,” Joshua said.

There are varied levels of investment in the discourse on equity and inclusion on the campus. Two years ago, there were a series of incidents on Boyer and Isaacs streets where students, mainly women of color, were yelled at, assaulted and harassed.

“What underrepresented students said to us was: Why is it that we are the only ones who seem to be feeling the pain, but all of our white colleagues are just walking around like this is not happening to anyone?” Joshua said. “Until everyone feels that the question on diversity, inclusion and equity around what kind of community Whitman is going to be is important, until they really feel that they have a stake in everybody and in everybody being included, then we would just be talking.”