Madison Park Center Exposes Divisions in Approaches to Homelessness

September 24, 2015

The Walla Walla Alliance for the Homeless expects to move forward with controversial plans to build a day center for Walla Walla’s homeless on Pine Street. Plans for the site, known as Madison Park, have angered some neighbors and received a lukewarm reception from others working to address homelessness in Walla Walla.

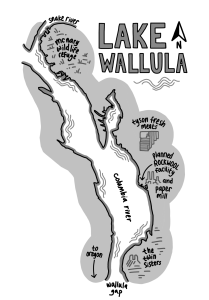

The Alliance formed early this year with the express purpose of creating the proposed center, which would sit on a disused lot directly south of Highway 12. They intend to provide shelter and showers for homeless in the area, and chose the location because of its adherence to zoning ordinances for both campgrounds and homeless shelters, as well as its proximity to downtown services. While early plans for the center included camping and RV hookups, the Alliance has since decided to make all housing there fixed, allaying concerns about a tent city on the site. Whitman alumnus and Alliance founder, Dan Clark ‘65, believes that the center could meet the need for accessible shelter with fewer strings attached than other area homelessness programs.

“Our primary objective is to provide a safe, legal place for people who are unhoused to be,” said Clark. “It’s a place to have your belongings, a place to sleep without fear of attack or of being rousted because it’s illegal. And it’s also a place for people to shower, to wash their clothes, to get mail.”

The Alliance met with roadblocks this summer when the Walla Walla City Council declined to grant an exemption from state energy standards for the one existing building on the property, a disused auto shop. The Alliance has already begun to refurbish the building to provide shelter and showers, but this repurposing means that the center would need to comply with updated energy standards in order to meet code, which could potentially delay the project and increase expenses. The exemption, which the city council would be authorized to create under a 1992 law, was requested at a July 13 work session but ultimately did not pass.

“It’s going to cost us more,” Clark said of the decision. “On the other hand, operating costs will be lower, so it’s not the worst thing in the world. It’s bad for the community – the community ought to have that kind of provision in its building code for this or any other building to help the community accomplish its goals.”

While most public debates on the proposed center have focused on the Alliance’s relationship with its new neighbors, the Madison Park project has also drawn criticism from other prominent figures and organizations in the fight against homelessness in Walla Walla. The last several months have seen the Alliance struggle to find a place alongside efforts from other organizations as well as the city and county governments to combat homelessness in the area. Several homelessness advocates cited a lack of collaboration between neighbors and other organizations in the early stages of planning as the chief roadblock to the project.

“I think there was a lack of communication between the Alliance and the neighborhood,” said Walla Walla County Director of Community Health Harvey Crowder. “I think they’re working hard now to take a look at what’s going on in the neighborhood and try to figure out where to go from there.”

This sentiment was echoed by Walla Walla Housing Authority Director Renee Rooker.

“Everything that we’ve done prior, we’ve always had community involvement,” said Rooker. “This idea was going through and the group that’s doing it didn’t contact any of the other housing providers. [They were] just kind of charging forward and not being inclusive in the conversation, and not sitting at the table with other providers of housing.”

In particular, the Alliance’s plan runs counter to the philosophy of “Housing First,” which guides Walla Walla County’s 5-year plan intended to end homelessness in the county by the end of its span. Housing First, as its name suggests, focuses on providing affordable housing to homeless persons in order to provide the stability they need to deal with any other issues they may face. The philosophy gained national attention after a dramatic success in the state of Utah, where chronic homelessness declined by 72 percent between 2005 and 2014, according to the state’s Department of Workforce Services.

Walla Walla County has an estimated 35 chronically homeless people, a category distinguished by being homeless for a year or more or during four or more episodes over three years due to some disabling condition. The 5-year plan seeks to put these 35 into housing by the end of 2016 and use the funding freed up by reducing stress on shelters and transitional housing to put other homeless persons into homes. These homes would be privately rented with assistance from the county.

“We believe that with our changes in resource allocation… if people are homeless and need shelter, we can quickly move them into shelter and then move them… back into permanent housing rather quickly,” Crowder said. “Some of that will require the reallocation of resources and changing people’s approach… and then looking for some additional resources.”

The Walla Walla Housing Authority has already done some work in this vein in the neighborhood surrounding Madison Park, where it has its headquarters. A large bloc of housing that the Housing Authority worked to make accessible to low-income populations sits near the lot, and many neighbors believe that the proposed center would set back the neighborhood’s development. Among these are the Housing Authority itself and Rooker, who lives in the area.

“We… are all about sustainability, and meeting the needs of all income populations with dignity and respect,” Rooker said. “We… have worked hard in that particular neighborhood to provide a variety of housing choices.”

The code requirements could be a major setback for Madison Park, the cost of which have yet to be determined. The Alliance’s original plan was to complete the center by winter, a goal now jeopardized by time and funding constraints. Whether or not that goal is met, Clark anticipates that the site will be ready for operation sometime next year.

With opposition still strong, members of the Alliance have begun meeting with neighbors and other housing-centric groups in hopes of easing tensions surrounding the Madison Park project. The Alliance held meetings with the neighborhood and community leaders throughout the summer in order to allay fears that the Madison Park site would be a tent city, as early critics feared. While the site would still include tents and RV’s, Clark emphasizes that the Alliance intends to focus on more permanent structures.

“Our goal… is to build out, to have them nearly all… be tiny cottages,” Clark said. “We hope to provide good information and allay some people’s fears about this, that or the other thing.”

Among the various groups fighting homelessness in Walla Walla, the conversation is turning toward coexistence and collaboration. Clark is skeptical that the County’s plan will achieve its ambitious goals, but he and the Alliance laid out a parallel plan promising to work alongside the county and other organizations rather than against them.

“We have a five-year lease on this property, and we’re adopting our own Walla Walla Alliance for the Homeless five-year plan, and that calls for us to cooperate with [the County], to help achieve those ambitious goals, so that we end homelessness entirely in five years… We have a five-year lease, and we’ll close down in five years if it’s no longer needed,” Clark said. “On the other hand, we will continue to deal with immediate human needs between now and such time as [the county] achieves those goals.”

Rooker is skeptical but hopeful.

“Can we get to a better place, and can we not have this kind of friction going on?” she said. “I think time will tell.”

Erich Shepherd • Sep 28, 2015 at 1:50 pm

This article seems to be missing the Housing Alliance’s response to allegations that the Housing Alliance is not communicating and that Housing Alliance plans run counter to the philosophy of “Housing First”.