11/8: The Day the World Trumpfed

November 17, 2016

Most of us spent the days following the catastrophe in a daze. You could see it in the eyes: professors, students and administrators gazing vacantly into space, as if they had all just witnessed a plane crash. Whole class periods were spent discussing how to go on—how to recognize the common humanity in the one-fourth of eligible voters who just gave a misogynistic, racist, anti-environmentalist megalomaniac the highest office on our dying planet. But there was always the underlying sense that these discussions were at best an anesthetic and at worst a desperate attempt to adapt. Many of us secretly believed that by trying to empathize with the dark forces that gave rise to Trump, we were really succumbing to them.

And in trying to recognize the common goodness of our fellow citizens, our discussions inevitably turned away from the voters to the systems. Trump lost the popular vote, so clearly there is something wrong with how elections are done. Abolish the electoral college, we all agreed. But what we didn’t realize—or refused to recognize—was that the roots of the Trump victory are more ideological than systematic; they aren’t something that will go away with obscure reforms to the already existing systems—they are too deep-seeded, too human for that. Instead, we must return to the voters—to the veteran that can barely pay his heating bill, to his desperate pro-Trump pleas on Facebook, to his rosy-cheeked 8-year-old daughter shivering under 3 blankets.

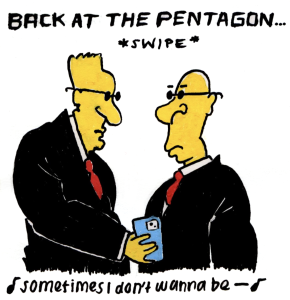

But, of course, his pleas won’t reach most of us. They will only be heard by fellow Trump supporters, just like our pleas for the poverty-stricken immigrant will only be heard by fellow Millennial progressives. The algorithms that underly our interactions see to that. The prospect of crossing the ideological divide is becoming fainter and fainter as time goes on. No longer can a radical progressive compose a protest song that will be heard by people on both sides of the aisle. No longer can a conservative preacher deliver a sermon to secular progressives. Most of the time it’s the filter bubbles that keep us from crossing the divide, but even when the filters break down we find that it’s too easy to turn to self-gratifying media—to media that accords with our preset beliefs.

In my last article I discussed why I think it is important to consume media that makes us feel uncomfortable about ourselves. What I didn’t discuss was that consuming this sort of media doesn’t just widen our own world views, but also makes it easier for people with contrasting ideologies to engage with us. If we avoid forming closely-nit partisan groups and instead interact with people all across the spectrum, we create a messy ideological space where polarization becomes difficult. There’s a reason, after all, that people living in population centers tend to be less racist, misogynistic and xenophobic—that is, less Trumpian—than people living in more isolated places.

Now, I’m not so naive as to believe that polarization will ever go away. No doubt there are some people that are so far gone that any attempt to interact with them will result in fisticuffs, and I’m also aware that Trump’s rhetoric has expanded the Overton window—the sorts of rhetoric that the public will accept—to such a degree that we’ve all become a little more racist and misogynistic just by talking about him, but I think this sort of engagement is the only real hope we have of averting total collapse.

Val • Nov 27, 2016 at 2:52 pm

Thoughtfully and perfectly stated.