Why so many Americans are quitting their jobs

February 10, 2022

In April of 2020, as COVID-19 spread across the U.S., the unemployment rate skyrocketed to 16.3 percent, something the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics had never seen before in its reporting history. 20.7 million jobs were lost in a single month. The Omicron variant is once again challenging this number, leaving many employers short staffed—including Whitman College and Bon Appétit.

In Washington State, the unemployment rate was 4.5 percent at the end of 2021, compared to 5.3 percent in March 2020, just before COVID-19 reduced the income of millions of Americans. The Omicron variant’s effect on the job market pales in comparison with that of the initial coronavirus wave. But it’s still taking its toll.

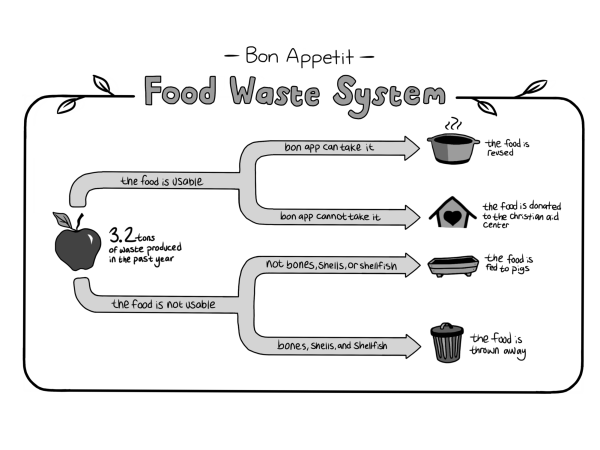

Shannon Null, general manager of Bon Appétit at Whitman, said in an email sent to The Wire that the company has “experienced intermittent labor shortages due to COVID-19 exposures that resulted from community spread in Walla Walla.”

In January of 2022, Walla Walla had the highest positivity rate seen yet, preventing infected people from working.

Employees are required to be vaccinated to work for Bon Appétit at Whitman, and over a third of Walla Walla residents have yet to receive the COVID-19 vaccination. Required vaccination can deter some residents from applying.

In an email sent to The Wire, Telara McCullough, Whitman’s director of human resources, noted an increased number of “retirements and resignations which is not consistent with past trends” at Whitman and “is causing a higher number of vacancies.” She credits these vacancies between “new job[s], retirement, general dissatisfaction and relocation.”

McCullough described the phenomenon as the “Great Resignation,” a term being used by economists to account for 2021 having the highest resignation rate in U.S. history.

These mass resignations can be attributed to the financial cushion offered by government stimulus packages and employees seeking better paying jobs with different hours or conditions.

Employees end up picking up the slack, taking on responsibilities outside of their job description, potentially slowing down work.

To attract applicants to vacant positions, Whitman’s Board of Trustees approved an increase to the salary pool for the next fiscal budget and “introduced a hybrid work policy and enhanced benefits,” McCullough said.

Although labor shortages are causing upheaval for employers, it could be an opportunity for better working conditions and better pay. Employers might be more inclined to cater the position to their workers and be motivated to meet the preferences and needs of their employees. Minimum wage has long been regulated by federal and state governments, and now that it’s in the best interest of many companies to raise their baseline pay and offer more benefits, legal wage requirements could be an issue of the past.

As the “Great Resignation” takes its course, unpredictable employment necessitates patience with Bon Appétit and Whitman faculty and staff, as well as with service providers in the community at large.