Senior Reflection: Glimpses of Greatness

May 17, 2016

Hello. My name is Abby. Three things that might explain my existence are: one, my new favorite flavor of ice cream is miso-cherry, which may sound overwrought but is really a new twist on the classic sweet and salty pairing; two, the most embarrassing thing that has ever happened to me occurred two summers ago when I peed my pants on a date; and three, if I ever get a tattoo, it will be the first word I learned how to read, which was “the.”

This year, in addition to discovering that delicious dessert, I’ve also realized that I am a story teller. I don’t write poetry and I don’t create characters, but I do spin yarns, so to speak. My word nerd tendencies sometimes manifest themselves in weird grammatical hang-ups, but what truly inspires me are those moments when language captures something perfectly. While I’m sure you’re curious about how that date went down, I have a few other anecdotes that I’d like to share.

I’ve studied Spanish since I was five, and somewhere along the line the lessons that my parents made me attend as a child turned into a major. Last year I studied in Granada, Spain, where I made an important discovery about my Spanish-speaking abilities. My vocabulary in English is a well-stocked arsenal—I can choose from a wide range of verbal weaponry and be profane and academic at equal turns, mixing registers with ease. The inspirational quote that I keep on my computer desktop, for instance, reads “I shit eloquence.”

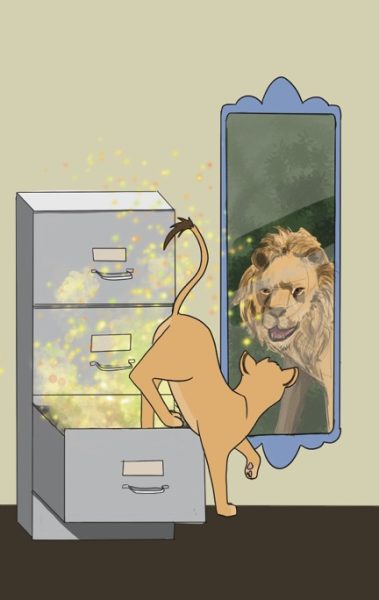

My Spanish vocabulary, though… it’s like that one drawer in the kitchen. Every house has one. The catch-all place with no clear system of organization for all those gadgets that don’t belong anywhere else. The thing about the miscellaneous drawer is that everything in it is useful, like those plastic, pointy sticks for peeling oranges, but specialized (I’m not about to use one of those to skin an apple). The contents of the drawer only help you in certain situations.

This is why I arrived in Spain after 15 years of exposure to the language not knowing how to say “doorknob.” It’s also why my experience reading Foucault in Spanish in a 400-level class about hypertexts did little to aid my understanding of an improv show we attended for my theater course. Turns out I’m better equipped to pretend I know pretentiously dense theory than I am to understand rapid-fire Spanish humor. The show was a barrage of slang I hadn’t heard, idioms that didn’t translate, and cultural context that I lacked. The most overwhelming part was when one of the actors literally sat in my lap for about ten confusing seconds. To this day, I can only report that I think she said something about contractions. I think.

While I was abroad I generally concluded that fluency is an evasive little bastard that I may never catch. One night at a bar with a friend, I was completely stymied by trying to explain “Jell-O” in Spanish, which was like a hellish round of Taboo because he didn’t already know what it was. I settled for “a dessert with fruit flavors that isn’t liquid but isn’t solid.” That’s not wrong, per se, but that description hardly does justice to the bizarre wiggliness that is Jell-O.

One of the greatest regrets of my college career was a moment in which I failed to take advantage of the vocabulary I’ve so carefully curated. One night at a group study session at a basement table in Penrose, a friend started ranting about PC culture at Whitman. He complained about how uptight students can be and said that if he wanted to use the word “retarded,” he would. And there I sat, surrounded by millions of pages of text, unwilling to utter a word.

It is unlikely that I missed an opportunity to dramatically change his perspective. But if we had that same interaction today, I would at least turn that speech into a conversation, because I wish I had said that words have power: that even if someone says “retarded” without intending to demean a whole group of people, that usage still links “messed up” or “broken” with mental illness or disability. Those associations may seem inconsequential, but when they accumulate, like sentences in a paragraph and chapters in a book, they form a narrative that shapes how we think.

I recognize that my privileged lifestyle means that my problems are comparatively petty, that my linguistic issues may seem sheltered and academic. But this is the context in which I am fortunate enough to operate— as a student of literature— and words are microcosms. Have you ever wondered why the word “motherfucker” packs its figurative punch by violating a woman? Why does the squiggly red line appear under “fatherfucker” when I type it on my computer, as if it were a word and by proxy a concept that does not exist? Language does not exist outside of society’s ills—it perpetuates them.

I am not sure if I am religious. But when I do think about the greater force guiding my life, I like to conceive of it as an author, as someone who’s writing my life with a wry sense of humor and a wealth of generosity. Maybe it’s blasphemous to link the power of language with the power of God, but I think it’s beautiful, because in words we can all find the ability to create.

Those glimpses of greatness—when someone articulates exactly what you were meaning to say, when a comparison is so strikingly apt it surpasses what straight description alone would have accomplished—tantalize us because language is an inherently flawed tool. It fails me in pivotal library conversations, eludes me in translation, and renders me culpable of linguistic subjugation. Fortunately, this force that reifies norms also offers the potential to change them.

Hello. My name is Abby. Three things that might explain my existence are: one, my new favorite flavor of ice cream is miso-cherry, a preference that likely links me to limiting labels such as “hipster” or “bourgeois”; two, the most embarrassing thing that has ever happened to me occurred two summers ago when I couldn’t find the syllables to say that I needed a pit stop; and three, if I ever get a tattoo, it will be the word “the,” because despite English’s imperfections, “the” is the article we use as an act of designation, a moment of mastery in an unwieldy medium.