The OP kid archetype

September 23, 2021

Nothing could have prepared me for how pervasive Whitman’s outdoors culture is. My first day on campus, I maneuvered through Ankeny’s web of slacklines to meet my Chaco-clad peers, utterly out of my element. Flyers advertised an upcoming kayaking trip. Carabiners dangled from belt loops. Everything lent itself to the idea that I had landed in an REI catalog brought to life.

A certain level of outdoorsiness is to be expected at Whitman; its promotional material boasts its 1:1 student-tree ratio and well-equipped climbing facilities; and its Pacific Northwest location connotes a certain crunchy quality. Still, its ubiquity is hard to anticipate—Whitman College is overwhelmingly outdoorsy.

Take a stroll around campus and you’ll see it: the skis and kayaks strapped to the tops of cars, the Nalgenes and their pine-tree stickers, the masses of Environmental Studies majors. I generally consider myself a vaguely outdoorsy person—I’ve been backpacking! I own a Hydroflask!—but here at Whitman, I am decidedly indoorsy.

When I sit down with senior Lucy Evans-Rippy outside the library, two boisterous lines of Whitties spread across Ankeny fifty feet away from us, tossing Frisbees and exchanging chants. I ask her if she had expected this—Whitman’s zealous outdoorsiness—before she enrolled.

“No,” Evans-Rippy said. “I had no idea. It was the biggest surprise of my life.”

Evans-Rippy describes herself as a generally indoorsy person, though she enjoys the occasional hike or day in the park. Outside of classes, she likes to read, write, drink tea and participate in theatre. When she first got to Whitman, she felt pressure to conform to the campus’s dominant culture, before realizing that she didn’t need to fit into the mold of a “profoundly outdoorsy person.” Now, she’s surprised she ever considered it and muses that she likely wouldn’t have felt the same pressure at most other schools.

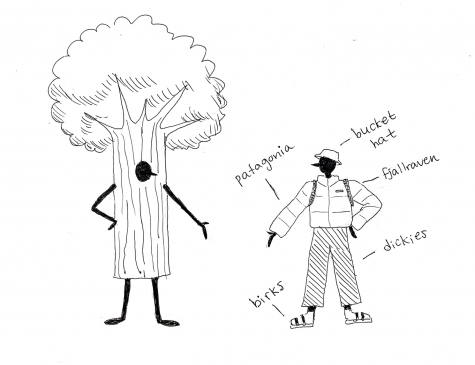

Illustration by Ally Kim

“I never would have suddenly been like, maybe I should take off my shoes and get on this string that’s tied between two trees and, like, try walking on it while everyone else around me watches,” Evans-Rippy said, in reference to Whitman’s affinity for slacklines. “But, here, I did briefly consider it.”

So where have “indoorsy” Whitties found their niches?

“I’m involved in a lot of personal creative pursuits,” Kyle Kim, a senior English major, said. “I can completely lose track of time working to bring those ideas to reality.”

“Being a part of the Women of Color Voices group [has helped me find my place],” junior Nomonde Nyathi said. “Those are people I feel like I closely identify with, and we can all relate to sort of similar situations, you know?”

Nyathi has also found purpose in community engagement, which has helped her get to know Walla Walla and its residents. She currently serves as co-leader of Whitman’s Buddy Program, which pairs students with Walla Walla residents with developmental disabilities.

“I mean, I would say [I’ve found my place] in the theatre building, because that’s where I’ve spent a lot of time,” Evans-Rippy said. “Honestly, maybe in the library.”

For many students, this culture can feel alienating. In addition to simply not appealing to a solid portion of Whitman’s student body, the breadth of knowledge and costly paraphernalia is widely inaccessible.

Whitman prides itself on a down-to-earth lack of pretentiousness, but its woodsy character suggests wealth and privilege in its own right. When I think of the archetypical ‘OP kid,’ a nickname for central-casting frequenters of Whitman’s Outdoor Program, I think of a student with access to expensive gear, childhood skiing lessons and generational wealth. They might sport a Patagonia jacket and Osprey backpack, and they’re probably white.

“Very outdoorsy,” Nyathi said, when asked how she would describe the average Whitman student. “It’s not a bad thing!”

She also called them adventurous, connected and eager to explore the community around them.

Kim said the average Whitman student is passionate and enthusiastic about getting involved on campus.

“In a hammock, no shoes, a lot of Patagonia, probably,” said Evans-Rippy.

Different perceptions arise here. We see one broad impression of an enthusiastic, committed student, and another of the aforementioned ‘OP kid,’ who dominates Whitman’s overarching vibe.

What does this mean for people who don’t fit into the latter category? Nyathi discussed the somewhat myopic perspective that some students seem to have. She explained that, as an international student from Zimbabwe, her experiences often strongly deviate from those of Whitman’s more outdoorsy students, and not everyone is able to recognize that.

“If I told people, like, I don’t go camping, or I don’t own hiking boots, they would be like, what do you mean? Everybody has that stuff.”

Many students feel intimidated by the Outdoor Program, both because of the massive expertise and involvement of some students and because they might perceive themselves as unwelcome. I have never set foot inside the OP rental shop and likely never will, partly because of how daunting it feels.

“I think because there are so many people who are so, so strongly outdoorsy, it removes other people who are just, like, partially outdoorsy from even getting involved, because it feels like you can’t fit the full box of what they’re asking for,” Evans-Rippy said. “I was definitely deterred.”

On the other hand, the Outdoor Program has made strides toward accessibility.

“Considering things like the OP fund, I feel like the program takes an effort to push towards being inclusive at the very least,” Kim said.

The fund in question is the Bob Carson Outdoor Program Fund, or BCOF, which provides every Whitman student with a $150 yearly budget to spend attending OP trips or renting gear. This helps lighten the financial pressure of outdoor excursions and increases access to resources.

When asked if she thinks the Outdoor Program is inclusive, Nyathi said both yes and no. Technically, there are no restrictions on who can or cannot participate, but she said that the OP isn’t always actively inviting toward those with little experience.

“But I can see, since my first year, how Whitman has made the effort to try to involve more members by creating events for clubs and affinities,” Nyathi said.

One example is the BIPOC Outdoors Club, a student-founded organization that seeks to eradicate the barriers preventing students of color from participating in outdoor activities at Whitman. The club provides financial coverage as well as an inviting, low-judgment atmosphere, hosting climbing nights, get-togethers and outdoor excursions exclusively for BIPOC students.

Despite this movement toward inclusivity, the prevalent lifestyle and aesthetic of Whitman, in all of its sustainable, granola, quintessential-Pacific-Northwest glory, remains inaccessible to many, intimidating to some and simply not of interest to others.

In the future, Evans-Rippy hopes that Whitman can move toward a broader, more heterogeneous social culture.

“I don’t know how that would happen,” she said. “Or if it will ever happen here. But, that’s what I would hope for. Social inclusivity outside of one interest or field.”

In some ways, this feels like a lofty goal. I have to question the limits of inclusivity, when the knowledge, lingo and groundwork of outdoors culture are entrenched in something unfamiliar to so many. Perhaps Whitman can work toward a more diverse and inquisitive social culture, celebrating the broad and varied interests of all of its students.