Leaving Afghanistan for Whitman

September 16, 2021

Angela Eliacy is a first year Whitman student, an undeclared intended economics-math major. She was born and raised in Afghanistan—first in the countryside, then in Kabul—before spending three years of high school in Japan. She enjoys boxing and is pretty good at it, or so she said. And, she left for the US from Afghanistan just two days before the Taliban took over her country. Her parents and nine of her ten siblings remain in Afghanistan, laboring through visa applications.

Afghanistan spent the 1980s engulfed in a war with the Soviet Union, and at its conclusion were left without a central government. Civil war ensued. The Taliban took over in 1996 and held power until 2001. “Those [five years] were some of the darkest days in Afghanistan, especially for women,” Eliacy said.

The US arrived in October 2001, nearly two decades ago, bringing about a trillion-dollar war along with a dollop of improved living standards: particularly for Afghan youth. “Women could study,” Eliacy said. “I could go to school, I could go study abroad.” Her generation could afford to live differently, and more modernly—outside the narrow scope of the ‘traditional’ Afghan child.

However, Professor of History Elyse Semerdjian says that the US installed in Afghanistan “one of the most corrupt governments on the planet.”

Semerdjian also noted that the War in Afghanistan could have concluded in two or three years. In 2003, the Taliban were offering to hand over Osama bin Laden to the US. But the US refused, because they wanted “blood” and “vengeance.” “Although [the US] said they were not into state-building, there was clearly a larger design of what they wanted to do in Afghanistan,” she said.

Eliacy was born in 2003, and the following year, Afghanistan held its very first direct democratic elections.

Nevertheless, Eliacy grew up fearing the Taliban and their frequent attacks.

She graduated from high school in Japan this past spring but was unsure of whether to return to Kabul or not. Her family was scared, aware that the Taliban could come at any moment. Missing her family, she decided to fly home. Once there, her parents kept her inside, as the Taliban were known for attacking public areas.

“No one goes out of their house without thinking about whether they will be alive when they come back,” Eliacy said. “Wives are worried about their husbands when they go out; parents are worried about their children when they go out. I don’t remember a week where I didn’t hear the word ‘Taliban’ or ‘suicide attacks.’ That’s pretty much how everyone lives there.”

Eliacy ultimately left for Whitman on Aug. 13. In Seattle, on Aug. 15, she received a text from her sister stating that the Taliban had arrived.

“I was crying; even my sister was crying. We were so scared. We thought that they would just start killing everyone. That’s how scared everyone is of them,” she said.

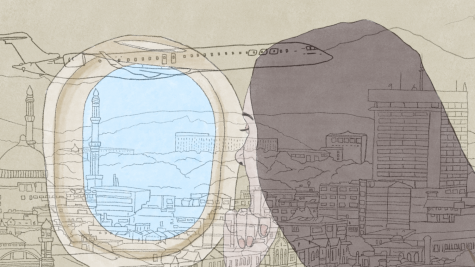

“When the flight took off from Kabul, I kind of had the feeling that I wouldn’t be able to come back home,” she said. “I sat beside the window, and I was looking down, and I was crying. I felt like everyone in Kabul was saying bye to me. I was looking at every mountain there, everything, like ‘this is gonna be my last time.’ With how I grew up, I would think the Taliban wouldn’t allow me to go in the country anymore.”

Although the Taliban claim that they’ve changed their ways, Afghans are doubtful. “No one is happy when we don’t trust them,” she said. Women are forced to wear burqas once again, hiding their faces and bodies. “You’re in your prison—they just tie you in clothes.”

Her brother’s restaurant is shut because people don’t dine out anymore. Her two sisters, ages 13 and 17, are stuck at home, unable to attend school. Their family shares one burqa, and they take turns wearing it.

Semerdjian laments Eliacy’s generation of Afghan youths, who had opportunities to get educated and participate, but are now being closed out of society or running for their lives.

“I feel horrible for all these Afghans whose lives were built up, through occupation and through the installment of a US-allied government. Now, we are responsible for taking care of those people,” she said. Xenophobia, a brutal immigration system, and Biden’s unwillingness to undo some of Trump’s foreign policies were listed by Semerdjian as barriers for embracing refugees.

Eliacy revealed that in some provinces, women and girls—some as young as 12—have been taken as sex slaves. “It’s just too much to take,” Eliacy says. “Anytime something can happen, and I don’t want to receive a call from my family saying something horrible happened to them.”

Fears that the Taliban would overtake the airport circulated among their household. Though the New York Times reported on Aug. 12 that the US expected Kabul to withstand pressure for at least another month, that month became three days. Eliacy’s family is under additional threat because her brother works for the UN, several of her siblings are associated with the US, and they identify as Hazaras, as well as Shia Muslims: ethnic and religious minorities, respectively, that have historically been oppressed by the Pashtun/Sunni majority.

Semerdjian explains that the Taliban’s particular brand of Islam is called ‘Pashtunwali.’ “It’s actually a Pashtun tribal law, and it’s informed as much by tribal conceptions as it is by Islam,” she said. “It’s a puritanical movement.”

Despite the ample criticism directed toward the US’s twenty-year occupation, Eliacy still views their actions positively. “That’s when human rights came to Afghanistan; women’s rights came to Afghanistan,” she said. “And I could get to go to school. My brother got a job. When my brother got a job, that’s when everything changed for our family.” Eliacy recalls taking care of cows and sheep when she was just 7 years old. Living in the village, she would spend two hours every morning walking to school. They were able to move to Kabul, where school was a comfortable five minutes away. “I had so much of a better chance to study.”

But going with public opinion, she agrees that America’s exit was unacceptable.

Semerdjian cites that, of the two-plus trillion American dollars poured into the war in Afghanistan, only two percent had even reached the Afghan people. “They were still living in poverty … I know some people saw improvement, but 98 percent of the money we had given was just staying within the Afghan and US militaries, but not trickling down to the people,” she said.

Eliacy’s family has applied for Indian, Pakistani, and even American visas. “Any option that can take them out of Afghanistan,” she said.

Eliacy is doubtful that she will return to Afghanistan for the time being. “That’s why I’m trying to somehow at least get part of my family out, especially those who are endangered now, so I can go visit them somewhere else. I’m sure I can’t go if the Taliban are there,” she said.

Eliacy explained how touched she was by all of the fundraising donors, mentioning one specific comment left for her: a Japanese woman had recounted how Eliacy and her classmates helped her in 2019, following a typhoon in their region. Eliacy called this a great lesson, and said with confidence—“that if you help people, you will receive their help.”