Review: “Isle of Dogs” is Beautiful but Disappointing

May 3, 2018

Wes Anderson’s “Isle of Dogs” is a visual spectacle that never quite escapes the stereotypes of a large-budget Hollywood release. Set in a near-future Japan, an authoritarian leader banishes all canines from Megasaki City to Trash Island after a vicious virus spreads through the population. These dogs, many of them afflicted by the virus, are left to fend for themselves in a post-apocalyptic landscape complete with ruined amusement and industrial parks. Atari, a young boy under the guardianship of Japan’s leader, steals away one night in search of his lost dog, Spots. He crash lands on Trash Island and is rescued by five alpha-male dogs: Rex, King, Duke, Boss, and Chief.

The film that follows divides its attention between Atari and his rescuers, Mayor Kobayashi (the leader of Megasaki City), a team of scientists aiming to cure the virus and a student protest group headed by an American foreign exchange student. While “Isle of Dogs” may seem interested in following the activities of a human ensemble, it instead relies on the dogs to bring personality to this film with a mix of personal tragedy and abuse, along with joyous and absurd character traits.

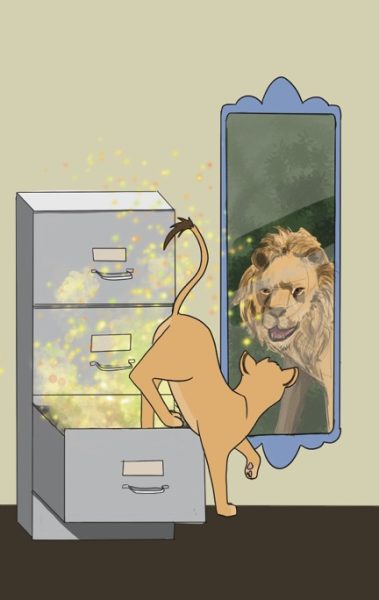

This is particularly evident in Chief (Bryan Cranston) who, as his name might imply, takes front and center stage in the film. Anderson has dedicated much of his budget to the outstanding stop-motion visuals of “Isle of Dogs.” Chief is a mangy stray, but the movements rendered in the frame-by-frame motion suggest a history of living tooth-and-nail where he has always come out on top, but never without scars. Cranston further explores the character with his wide vocal range from the gruff street brawler to pampered hound. While the other dogs are all lovable, they act more as a mirror with which to further explore the solitary Chief.

The visual splendor of “Isle of Dogs” must also be applauded. It is an artistic celebration not only of Japanese art, but also of Wes Anderson’s own unique distortion of stop-motion. The origins of this can be seen in Anderson’s 2009 masterpiece, “Fantastic Mr. Fox,” which shares a similar character aesthetic. “Isle of Dogs” also uses stop-motion to subvert audience expectations. In the character introductions, one of the dogs bites off another’s ear. While it is not needlessly graphic, there is blood spilled, and later the ear is seen being dragged off by rats. These images are startlingly out of place in an animation, that it immediately draws viewers in. Indeed, “Isle of Dogs” is not a children’s film; it deals with adult themes including depression, suicide, sex, commitment and even genocide.

However, “Isle of Dogs” is not without noticeable flaws, the greatest being the characterization of the American foreign exchange student, Tracy Walker (Greta Gerwig). The film may concentrate on the dogs, but when it is examining politics, it does so through the vocal Japanese student protest group which, for some unknown reason, is led by Walker. While her fellow students play key roles in the final plan to overthrow Kobayashi, Walker is ultimately the savior of the day–a white savior character. There is no reason why she needed to be non-Japanese to see through the veil of propaganda, and yet it is Walker, of all the human characters, that gains the most personality.

This problem is further confounded by Anderson’s sparse use of subtitles or translators. Only when it is absolutely necessary to further the plot does the film offer some form of translation. This leads to Atari, at least to non-Japanese speakers, appearing to be a character of little to no characteristics. Without dialogue to suggest intent, Atari never evolves from the commanding little brat he is first introduced as.

“Isle of Dogs” is easy to be visually amazed by, but a non-linear plot and over-reliance on Tracy Walker makes the film a disappointing addition to the repertoire of a stunning filmmaker.