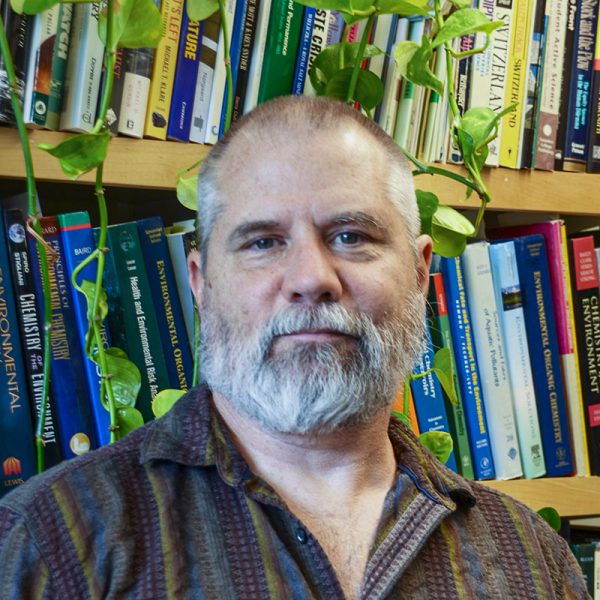

When I enter Frank Dunnivant’s office, I am greeted by a plethora of plants, some towering to the ceiling. He’s wearing a purple tie-dye shirt and sitting criss-cross applesauce in a swivel chair. When I ask him how he’s liking the snow, he simply tells me that it doesn’t stop him from wearing his beloved Birkenstock sandals year-round (no socks).

Frank Dunnivant began teaching chemistry at Whitman College in 1999. He graduated from Auburn University with a bachelor’s degree in Environmental Health. Later, he attended Clemson University, earning his Masters and Ph.D. in Environmental Engineering. An analytical environmental chemist and researcher, Frank has been involved in countless projects, mainly in the study of PCBs and hazardous waste chemicals in the environment. Aside from teaching both lower and upper levels of chemistry, he is a member of the environmental studies committee and a former chemistry department chair.

Wire: Would you mind introducing yourself and talking a little bit about who you are, what you do and what drew you to Whitman?

Frank Dunnivant: This is Frank Dunnivant, I came to Whitman in 1999; I teach chemistry. I was a nomadic scientist and had lived in many states and countries [before coming to Whitman College] but was offered this job here in the Pacific Northwest.

Wire: What appealed to you about the Pacific Northwest?

FD: I came here to see Grateful Dead concerts in the early to mid 90’s, and I decided I needed to be here. I just love this place.

Wire: Why did you choose teaching? What led you to it?

FD: I’ve done everything you can do with a chemistry degree, and this is the best gig ever. I love it. I’m 67 years old, and I do not see retirement on the horizon.

The thing I love the most is working with the incredible inquisitive minds the college has coming in. I see students come in enthusiastic but scared to death; they don’t have a lot of confidence. I watch them for four years and teach them as seniors – it’s amazing to see the character building and the confidence they gain.

Wire: That’s awesome. What interested you about studying chemistry?

FD: I grew up on a farm in Alabama with no educational mentor, and my parents wanted me to go to college. I was the second person in our entire extended family to go to college, but I did not do very well [in high school], and so I had to go to a Community College to get into a four year college.

I went to community college for three years and, looking back, I took just about every course they offered. My parents said ‘ok, you should go to a four year college and get a degree.’ I had two years left of college and they said ‘you need to find a major,’ and there was this thing called environmental health. I was fascinated with every class I took — I wanted to major in everything: psychology, sociology, history. But the science bug hit me because I could do math.

I thought about going back to work on the farm. Gene Wilkes [a mentor], figuratively grabbed me by the throat and said ‘go to graduate school.’

Wire: After that conversation, did you go to graduate school?

FD: I went and got a job in the consulting world. It was the 70’s so the environmental scene was crazy. I learned more working in the consulting world, the real world, than I did in any educational programs because there were no procedures. [At the time] the EPA had not told us how to analyze and do things — we just had to figure it out, it was incredible. But I learned everything I could after three years, and it became repetitive.

I went to graduate school and got my masters and Ph.D. in five years. After that I traveled the world; I would take a job and stay until I had learned everything and then take another job.

Wire: That sounds like it would be exciting.

FD: It’s not a great plan for most students, but it was great for me. I got to live in Switzerland, upstate New York and a bunch of other places. I worked for the U.S. Department of Energy for a little bit, did research and also taught.

Then I got a gig at a small liberal arts college in upstate New York and thought, ‘what have I been doing with my life?’ Teaching is incredible. After that I got this job [at Whitman College], it was in the Pacific Northwest, close to the coast, close to the mountains and a great school — I call it nirvana.

I didn’t know if I would stay here, because I’m nomadic. But no, I will die here.

Wire: That’s some impressive dedication to the job.

You gave a presentation to my Environmental Studies class last semester about chemicals in the environment, and it was very memorable. What are some surprising things about chemistry in relation to health that people might not know about?

FD: Every year I look at the “dirty dozen” fruits and vegetables [list], and strawberries are the worst thing you can eat when they are non-organic. The dirty dozen are the fruits and vegetables that they recommend that you do not eat if you are a child or are pregnant. There also is the “clean fifteen” which are generally [fruits and vegetables] that don’t require pesticides and herbicides to be sprayed on them, or have peels and husks that you can take off.

In one of my senior-level courses, we do an analysis of strawberries; we started this maybe 10 years ago… and in my household we do not eat anything but organic strawberries. You would not believe the chemicals that are put on strawberries.

Wire: Are the dirty dozen among some of the most notorious fruits and vegetables mostly because they are heavily pesticide laden?

FD: Yes, they have tested [the dirty dozen] and pesticides are the problem. In one of my labs we look at Captan. It’s supposedly used because it’s a fungicide and is sprayed on peaches and strawberries. In my opinion, they do this so the fruits can turn red because they know people don’t want to eat green strawberries. Raspberries, on the other hand, turn red naturally and do not usually have Captan sprayed on them.

Don’t eat the dirty dozen if you are young. At my age, it doesn’t really matter. But I don’t feed my kids the dirty dozen, only organic.

Wire: Beside the dirty dozen, are there any other food items people should avoid?

FD: Don’t eat fish that are high on the food chain. There are PCBs and PFAS in them at low concentrations. But these fish can have a lot of mercury. Our wonderful Alaska and Pacific Northwest Salmon are fine, as long as it’s sustainable. Farmed fish have at least an order or magnitude higher pollution than anything else.

Wire: How do high food chain fish ingest or absorb mercury?

FD: There are two sources of mercury. One is volcanoes; a lot of mercury enters into the ocean that way – we can’t do anything about that. The other source is coal power plants, which we have been drastically closing and reducing in the U.S. However, other countries like China and India continue to build them.

The good news is that solar and wind power have become much less expensive than coal fired power plants. 80 to 85% of our energy that we use and generate in Washington state is green – but of course we’ve completely destroyed the Columbia River ecosystem.

Another thing that concerns me, because I have kids, is the age that kids reach puberty in the United States, which has one of the earliest average puberty ages out of many developed countries — especially for people assigned female at birth. We don’t know what it is, some scientists are trying to pin it on one or two compounds, but I don’t believe that. It’s just our modern chemical way of life.

Wire: Are you referring to chemicals in our food?

FD: Chemicals in our food, cosmetics, the air and pretty much everything. We are dosing ourselves to the highest level in Western countries. In terms of cancer rates, the U.S., Europe and Australia have the highest rates.

About 10 to 15 years ago, someone had the sense to start analyzing makeup: lipstick, mascara and other things. Unbelievably high concentrations of toxic metals and phthalates were found. Both are blamed for a lot of health issues.

Wire: I’ve heard about chemicals in microplastics, which apparently are now everywhere. What do you think about this?

FD: Around 15 years ago scientists started testing for microplastics on beaches, finding [microplastics] on almost every single beach they analyzed. Since then, they have been found in the Arctic and just about everywhere, including in our bodies, in most of our organs. They can pass the gut-blood barrier; they have been found in our brains and in our tissues. [Scientists] don’t know if they are doing anything, but the fact that they have even been found in us, bothers me because PFAS and BPA are in these plastics.

One of the biggest sources of PFAS to college students, I think, is microwave popcorn. I banned microwave popcorn from my house about ten years ago. You actually can taste how microwave popcorn is different from regular popcorn.

Wire: Given your chemistry knowledge, are there things that you intentionally choose to eat?

FD: It’s more about what I avoid. We eat very healthy in my household. We are fortunate enough that we can buy organic, which is more expensive.

Wire: Is chemistry a puzzle piece to maintaining health, in the environment and within our own bodies?

FD: I don’t think one discipline can solve anything, it has to be an integration of all the sciences, which is why we have many combined majors [at Whitman].

Wire: Do you have any last words of advice?

Frank: My advice is to stay in school as long as you can, and never stop learning.