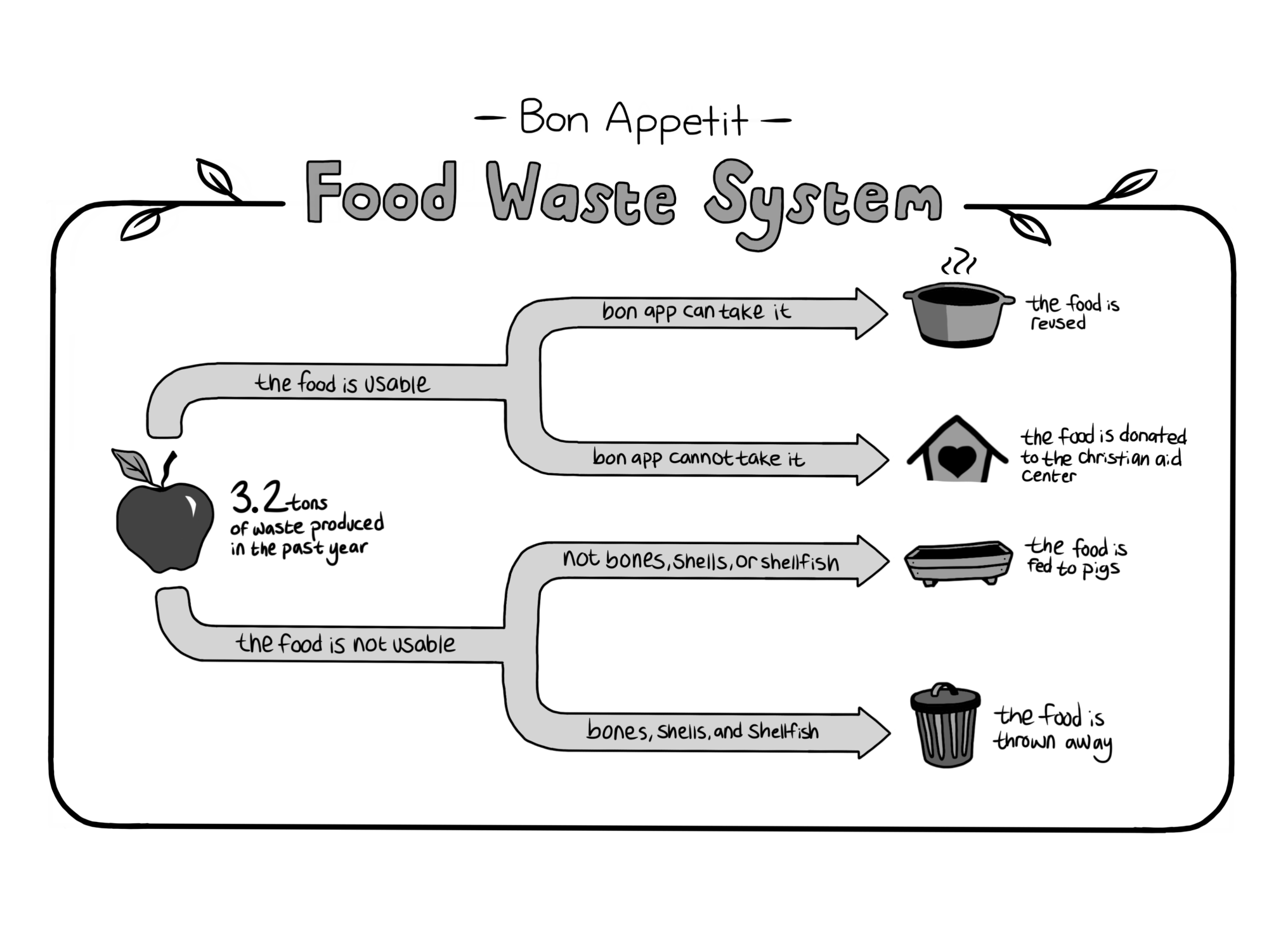

In 2019, a waste audit conducted by Bon Appétit and the Whitman Sustainability Office revealed 2,000 pounds of weekly food waste. A little more than four years later, food waste has plummeted by nearly 90 percent. From approximately 30 tons of food waste in 2019, Bon Appétit now boasts a yearly waste figure of 3.2 tons, according to the company’s internal waste measurement software. Considering the fact that Bon Appétit does not have access to commercial composting facilities, the staggering waste reduction is a mind-boggling achievement.

According to Shannon Null, the General Manager of Bon Appétit at Whitman, waste reduction is a huge point of emphasis both for her personally and for the wider Bon Appétit network. At Seattle University where Null worked before coming to Whitman, waste issues were less glaring because of the composting services available in Seattle. At Whitman however, Null became much more interested in creative waste management solutions because of the lack of robust compost and recycling systems available in Walla Walla.

“I’m a little bit beyond the deep end with it … We’re on our own, it’s almost like a little mini city. We can create our own things that work, and we’ve been recognized by Bon Appétit for doing more than other places,” said Null.

Since neither Walla Walla nor Whitman have composting capabilities, Null and Bon Appétit have worked hard to find creative alternatives for the food waste the company produces. The first step of the waste reduction journey was transitioning away from an “all-you-care-to-eat” buffet-style model to the current flex-dollar model when Cleveland Commons first opened.

Chef Tommy Whitehorn has been making food for Whitman students for almost 15 years, and he emphasizes just how significant the transition away from the “all-you-care-to-eat” model to the current flex dollars system has been for waste reduction.

“We used to have quite a bit of waste. I remember times where we would have buckets next to the dish pit and we would weigh it up. We could let the students know how much we were wasting,” Whitehorn said. “Now we’re ‘batch cooking,’ so we’re not cooking huge amounts of food at one time. [The old system] made it difficult to project how much food to cook. It’s great now.”

While the system transition made a significant reduction in Bon Appétit’s waste production, a commercial kitchen feeding hundreds of people daily inevitably produces compostable waste at a steady clip. When searching for an alternative to the landfill for the mountain of vegetable scraps and occasional moldy pieces of produce, Null found a solution via the local farmers Bon Appétit sources many of its ingredients from.

Over the last five years, Null and the Bon Appétit team have developed friendships with many farmers in the area, which have opened creative avenues for diverting waste from the landfill. The vegetable waste that comes out of the Cleveland Commons kitchen is dropped off at local farms, where it is promptly eaten by pigs. Over the last 12 months, local pigs have consumed about half of Bon Appétit’s organic waste, equal to 3,200 pounds.

However, local farmers are not just interested in food scraps to feed their pigs. Null described how farmers will ask for things she wouldn’t have thought to offer them: tofu containers become plant pots, old pallets are repurposed, cardboard transports new produce and banana boxes gain new life.

“We save all of that for them and put it outside [for local farmers to collect],” Null said.

Bon Appétit’s creativity with waste reduction also extends to the kitchen. Cooks are taught to use a “stem to root” philosophy, where every piece of a vegetable (or other ingredient) is used.

For example, parts of a vegetable that don’t make it to the salad bar or into a recipe like the root or the stem are used to make vegetable stock for the soups of the week. The philosophy is not limited to vegetables, as all kinds of usable leftover ingredients are saved and repurposed into another dish in the following weeks.

Chef Nimal Amarasinghe has been working at Whitman for over 13 years, and is a big proponent of the “stem to root” philosophy. Growing up, Amarsinghe said he ate 99.9 percent of the things available to him. His plate was always clean, he would never have to scrape anything into the bin. He draws on that mentality when he creates his menus today.

“When I started at Bon Appétit 13 years ago, I wrote the menus and I didn’t have a soup menu pre-decided. All of the leftovers are going to be my creative soup list,” said Amarasinghe.

Leftovers are especially a problem when a menu item that is expected to be popular does not sell as much as anticipated. Factors outside of Bon Appétit’s control can drastically alter the amount of food it sells, like the cold snap that recently hit Walla Walla. After several days of sub-freezing weather, Amarasinghe was left with an abundance of sausage that didn’t sell because fewer students (and community members) walked to the dining hall through the snow.

“A week ago we had sausage for the weekend [that didn’t sell],” Amarasinghe said. “Next week you will see Italian sausage and vegetable soup [on the menu]. So I’m not throwing it away. I cut down my waste as much as possible. My sous chefs help me a lot.”

Collaboration between chefs drives the leftover-repurposing process.

“We talk to each other and say ‘hey, I have extra chicken this week, can you use it for something this weekend?’ He has extra beans I can use, so we talk to each other,” Whitehorn added.

While Amarasinghe takes particular care to disguise the reimagined leftovers he includes in his dishes, some students are excited that the food they are served is made in a creative and earth-conscious way.

Sophomore Jorgie Hampilos is a regular Cleveland Commons diner, but wasn’t aware of many of the waste reduction practices the kitchen staff employ. Learning more about how Bon Appétit is working to reduce its food waste makes her more excited about eating at the dining hall.

“I’m a really big fan of leftovers. And I don’t really think you can tell [some food is repurposed] either,” said Hampilos. “It’s more efficient, I feel like they’re headed in a good direction.”

Bon Appétit might be headed in a good direction — and the numbers prove it — but there is still more work to be done. Null has a laundry list of project ideas and initiatives planned for further reduction of waste, including an overhaul of the company’s catering system, reusable takeout containers, an on-campus herb garden and a month-long waste awareness campaign.

One potential project rises above them all when Null discusses her future hopes.

“I want compost. That’s the dream. I think Whitman has it in them. I think we could manage it here, and it would make a huge indent if we just did it here, and I would be more than happy to manage something like that. It fits with what we’re doing, and not [composting] feels weird. I don’t like throwing food in the trash, period. I think students would feel better about eating here and dining in general. That would be the dream, and I don’t think it’s far off,” said Null.