OP-ED: Perhaps it’s time to allow Roe v. Wade to be overturned

December 5, 2019

Renewed attacks on women’s reproductive freedoms have impassioned feminists to put much time, energy and resources into ensuring that abortion remains a constitutionally recognized right. Primarily, the focus has been on safeguarding the security provided by Roe v. Wade, a 1973 Supreme Court decision. Roe v. Wade declared it unconstitutional for the state to interfere with a woman’s choice to get an abortion in the first trimester of a pregnancy on the grounds of a woman’s “right to privacy,” but maintained the right to limit her ability to do so in the second trimester, and ban it altogether in the third. This fight to preserve Roe is a losing battle.

Abortion rights are regulated at the state level, and this past year alone 11 states adopted laws that either make abortion illegal under any circumstances (this includes rape and incest), or severely reduce the circumstances in which a woman can seek a legal abortion. Many anti-abortionists hope that multiplication of these anti-abortion laws will in time suffice to persuade the U.S. Supreme Court to overturn Roe v. Wade. Doing so poses a great threat to women’s freedom and safety by stripping them of agency, regulating their bodies and leaving them with no legal leverage to defend themselves against male dominance. Yet fighting this legal battle with “rights” language has proven ineffectual.

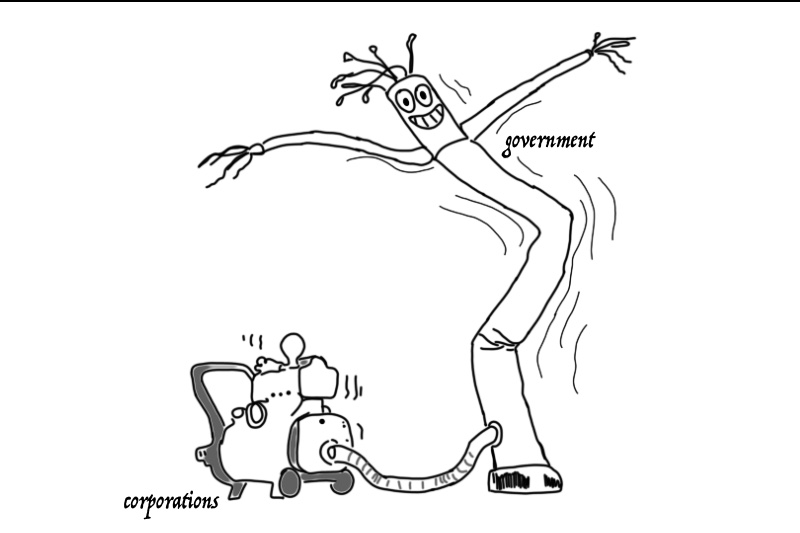

As Wendy Brown states in “Finding the Man in the State,” “the [liberal] state is a specifically problematic instrument or arena of feminist political change,” as it is an entity where “paternalism and institutionalized protection are interdependent.” Women’s dependence on the liberal state to grant them rights mimics what Brown refers to as the “powerlessness marking much of women’s experience across widely diverse cultures and epochs.” Dependence is not new to us. But, if it’s what we’re attempting to escape, we should not look to a masculinist state that is fundamentally compromised in its capacity to secure our freedom to do just that. It will not happen.

Not only does seeking rights from the state act to reinforce male domination, it also moves the burden of responsibility for abortion from the state onto the individual. Take the Hyde Amendment for example, which banned the use of taxpayer dollars for abortions except when the woman’s life is in danger or a pregnancy is the product of rape or incest. Such a law puts the financial burden of getting an abortion on the individual woman. For many women, this lack of funding means the lack of meaningful access to abortion. Without the capacity to exercise her rights, a woman’s “right” to abortion is hollow; it may as well be illegal.

Rights do not guarantee freedom. What they do is disguise the problematic structures that lead to the necessity of abortion to begin with. For a woman, the advent of a pregnancy means the loss of some other aspect of life — whether that be her career, her economic mobility and independence, or her autonomy – as the burden of childbearing and rearing is still made her responsibility. Current political structures will continue to show their true masculinist colors until we achieve equal participation in childbearing and raising.

In “Rights and Losses,” Brown explains that privatization “depoliticizes socially constructed problems and injustices.” It allows the state to shirk the responsibility of providing a context in which rights are meaningful, and instead “leaves the individual to struggle alone in a selfblaming and depoliticized universe.” At first, rights appear appealing to the woman seeking a sense of agency that has been lost in gendered oppression. But, as Brown goes on to explain, “rights may also be one of the cruelest social objects of desire dangled above those who lack them. For in the very same gesture with which they draw a circle around the individual, in the very same act with which they grant her sovereign selfhood, they turn back upon the individual all responsibility.” Rights privatize the political situation of a woman, obscuring the fact that her situation is a result of structural inequities.

Thus, to move a situation in which a woman is seeking an abortion out of the public sphere denies a legal responsibility for the oppression and limitations the law poses in the first place; it denies reparation for the legal injury done. When feminists fight to retain their “right to privacy” within the context of the liberal state, they are doomed to fail.

Thus, we are left with two options: we can continue to seek protection in rights that have extremely limited accessibility, or we can stop trying to protect Roe v. Wade and allow for the possibility that it be overturned. Whether or not it is, our need for freedom and equality cannot wait. We’d be best to put our time, energy and money into fighting against gendered oppression a different way.

Imagine if, instead of diminishing our fight by keeping it within a paternalistic structure, we women were to demand freedom on our own terms? As Audre Lorde so poignantly said, “the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house” — we must invent our own means of demolition and healing. What if instead of pursuing the right to privacy we pursued real substantive equality rather than mere formal equality under the law? Demanding equality would rupture the ineffectual and insubstantial claim to privacy, and necessitate examination of structures that compromise gender equality in liberal governance. Equality demands more than granting women individual rights or the same rights as men. Restructuring systems for equality would mean addressing poverty, racism, education, sexual and reproductive freedom and employment, to make them as beneficial to women as they currently are to men. It would demand societal reckoning.

Switching emancipatory tactics is not without cost. The abolition of Roe v. Wade would see the loss of life, livelihood and agency of women across the nation. Without safe, legal access to abortion, women will perform them by other means — means that are potentially fatal. The existence of abortions has never been contingent on their legality; the only thing contingent on legality is whether the abortions women have will be safe. Yet some mitigation is possible. Women can revive underground abortion service networks. This would itself be an act of refusing dependency. Clearly the liberal state cannot be repurposed under a feminist agenda; a feminist agenda must be the force to engineer a framework that genuinely supports equality.

Thus the question remains: are we willing to take emancipatory risk over the perverse comfort of the state’s protective unfreedom? How much are we willing to sacrifice to gain equality? This is no easy fight, and certainly not a short one, but we only prolong our oppression with the halfhearted feminism of today. Asking the state for freedom will not do. The time for asking is over. Now is the time to demand.