The real victims of homelessness

October 9, 2019

People don’t like seeing homelessness. It makes them uncomfortable. It makes them feel unsafe. It lowers the value of their waterfront properties. Does this make the middle class the true victims of the homelessness epidemic? Absolutely not.

There is a deeply disturbing rhetoric surrounding homelessness in this country, revolving around the idea that, on some level, the problem with homelessness is its visibility. In recent weeks Trump has pushed for a “major crackdown” on homeless encampments, and repeatedly insinuated that the homelessness epidemic tarnishes the “prestige” and aesthetic value of “liberal” cities.

Trump’s statements have been met with swift criticism from Democrats, but is what Trump is arguing actually any different from what Democrats have been saying and doing for years? People are quick to point out when Trump makes disgusting comments, but in this case, “liberal” sentiments aren’t any better. Even at Whitman College, homelessness is discussed with the same dehumanizing stigma, an attitude that reduces the struggles of poverty to an inconvenience for the middle class.

As outlined in The Washington Post, liberal voters continually pass laws that criminalize aspects of homelessness and call for police enforcement. Uprooting encampments, making it illegal to sit or lay on city streets, or fancy new apps that allow citizens to report tents and shelters are just some of the aggressive policies employed by cities like Seattle, San Francisco and LA.

My concern is that people’s outrage surrounding homelessness is tainted and rendered less productive by a deeply skewed sense of the issue. Homelessness does not become a problem when a white middle-class family stumbles upon a tent by their house in Seattle; it was a problem the moment a human being was forced to live on the streets in one of the most “progressive” cities in the world!

I am not going to do what many people wrongly do when talking about homelessness. I am not going to draw a line between the “deserving” homeless person and the “lost cause.” I am not going to argue that we need to focus on the homeless people who don’t do drugs, or attempt in any way to declare who is and is not deserving of our compassion. These sorts of distinctions are part of the problem.

Do many homeless people do drugs? Yes. Does that mean they become less deserving of compassion because they deal with addiction? No. Do many homeless people struggle with mental illness? Yes. Does that make them any less human? No. Why is that so difficult for us to remember? Rich people do drugs. Rich people have mental illnesses. Does that exclude them from deserving empathy? Of course not.

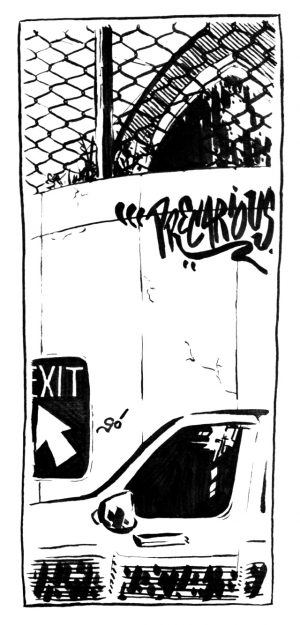

“I don’t want to have to see it!” is the rallying cry surrounding the homelessness issue, a cry Trump has picked up and weaponized against his political opponents. And I get it, we sit in our stylish apartments, in our shining cities on overly watered green hills and tell ourselves that the world is made for us. But homelessness will never be solved if we continue to pander to the middle class’s comfort level. It is time to look this issue directly in the eye, because while we apparently cannot give every man, woman and child a home, the least we can do is give them back their humanity.