Whitman’s Asian-American community reflects on Atlanta shooting, discrimination and identity

April 1, 2021

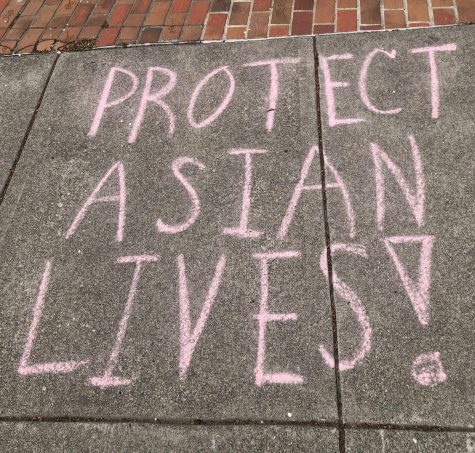

Heartbroken, frustrated, helpless, exhausted, overwhelmed, stressed. These are the words Asian-Americans at Whitman have used to describe how they are feeling after a swell in anti-Asian hate crimes across the nation.

COVID-19 + Atlanta Shooting

On Tuesday, March 16, six Asian-American women and two white individuals were murdered in a shooting in Atlanta. Since the shooting, awareness around anti-Asian hate crimes and recognition of the Asian-American experience has grown.

Assistant Professor of Psychology Chanel Meyers, who has researched anti-Asian hate speech, spoke on the combination of the pandemic and the recent events in Atlanta as related to the understanding of this growth of anti-Asian sentiments.

“Unfortunately, it feels like the Atlanta shooting served as some sort of confirmation of Anti-Asian sentiments in the country…it has existed for a really long time, probably under the surface or in ways people perceive as subtle…” Meyers said. “It shouldn’t take a mass shooting to legitimize a group of people’s experiences with discrimination and hate and exclusion in our country.”

Anti-Asian remarks like “China virus” and “Kung flu” that former President Trump championed, Meyers added, exacerbated the issue by giving people license to express these hateful beliefs.

Asian-American Identity + Experience at Whitman

Jenny Kim, junior and co-president of Whitman’s Pan-Asian Club (PAC), believes this moment is a wake-up call to Asians who haven’t processed what it really means to be Asian in America. She spoke about her experience at Whitman as an Asian-American woman.

“I have experienced a lot of microaggressions at Whitman,” Kim said. “Sometimes I just feel crazy because you think that it’s in your head and that you’re overreacting but when you experience them for your entire life, it just has a huge impact on your mental health and the way you perceive yourself.”

Reading headlines of grandparents being pushed into the street and hollow excuses from law enforcement for these acts of hate provoke deeply personal feelings for Asian-Americans.

“I’m just thinking about my family a lot,” Kim said. “They’re older, they immigrated here, they don’t speak English very well and they work so hard all their life to provide for me and then to think that they could be attacked while going grocery shopping or be verbally abused and called names and not know how to react, just thinking about those moments just makes me cry all the time. It’s not that they’re not strong, they’re the strongest people I know, but they’re in a foreign country trying to get by. I know a lot of other Asian friends I have are feeling similar ways.”

PAC’s other co-president, junior Jacob Nam, also spoke about his difficulty adjusting to the predominantly white make-up of Whitman’s campus and how he came to navigate his Asian-American identity.

“Coming to Whitman…it’s very hard to find your Asian peers and find your Asian identity,” Nam said. “I would always think, ‘Do I have to change myself to fit into Whitman? Do I have to become ‘white’?’ But I realized that I don’t have to change my identity, instead I need to embrace it more.”

Kim shared similar sentiments about confronting her identity. She realized that her upbringing in a predominantly white area has translated well to experience at Whitman.

“I feel like I grappled with my Asian identity all of my life trying to still be connected to my Korean culture and be proud of that identity while also experiencing so much racism. Just feeling like nobody really sees me and if they do it’s always me being Asian and what stereotypes are associated with that that comes first,” Kim said. “I feel like Whitman tries to have this color-blind approach and that just neglects all of the incredible identities and experiences people have here.”

Model Minority Myth + Invisibility

To Meyers, this theme of invisibility is rooted in the Model Minority Myth. This is the idea that certain minority groups that typically achieve a higher socioeconomic status lose some of their minority statuses. A Whitman So White podcast episode features student voices on this topic.

Meyers reflected upon the ways in which the Model Minority Myth affects how Asian-Americans are expected to come to terms with race.

“As an Asian-American, you’ve probably had these experiences where you’ve been invalidated based on your race, you’ve been judged to have certain characteristics based on your race, you’ve been slighted in some way, exoticized, fetishized — we’ve all had those experiences as Asian-Americans but it’s really hard to talk about those experiences without seeming like you’re trying to make things all about you now,” Meyers said.

“The Asian-American experience,” Meyers continued, “is largely defined by invisibility and now we’re finally visible in some sense. Which is good because we can talk about this without it seeming like we’re fighting in the ‘Oppression Olympics’ because that’s often how it feels.”

Pan-Asian Club + Community

The anti-Asian events of the past year have fostered a sense of connection among the Asian-American community.

On Sunday, March 21, PAC hosted an event in the amphitheater for American-Asian Pacific Islander (AAPI) students to be in each other’s company and reflect upon their experiences.

Meyers commented on the significance of this community and allyship.

“It’s nice because now I’m able to connect and solidify my connections with other Asian-Americans but also other allies who have been very vocal in their support and have been there for me. And the big one is intraminority allyship,” Meyers said. “It’s been really prevalent to me that the people who reach out to me asking if I’m okay are those of other minoritized backgrounds.”

On Friday, March 26, the Office of Diversity and Inclusion and several other AAPI-based identity clubs and affinity groups hosted a solidarity event focusing on bringing an end to Asian hate. Dean of Students Kazi Joshua considered this a space to recognize the lives that have been lost, and to bring AAPI together, but also to introduce one another to the real-life experiences of this complex topic.

“If we are silent we are complicit and so that’s an invitation for the community to be awakened to the suffering of those among us,” Joshua said.

President Murray’s Email

In addition to a video message condemning violence against AAPIs, President Kathy Murray shared an email with the campus community titled in support of Whitman’s Asian community.

“I wanted to take a moment to directly address the students, faculty and staff who are of Asian descent. We are with you,” Murray wrote. “Whitman would not be the college it is today without you as a part of our community.”

President Murray’s message left the AAPI community with more to be desired.

“I appreciate the intent,” Nam said. “But after reading that letter I didn’t feel a sense of comfort or consolation.”

Meyers echoed her disappointment at the belated response from the college.

“It’s okay to not know and be ignorant, that’s the first step… I know change is hard and I’d rather people just be very transparent about… what their intentions are rather than glossing over it,” Meyers said. “Blanket statements do read as those kinds of covers and I think that’s why a lot of minoritized people feel skeptical and distrusting of those kinds of statements.”

Call to Action

From an administrative standpoint, Joshua is working with several different campus offices to reinforce the college’s bias incident reporting and response system. He calls for the members of the Whitman community who experience targeted hate to be in communication with himself and campus security.

“We can enhance our own safety and security and communication mechanisms,” Joshua said. “It’s important to understand that if any member of our community is targeted, it puts everybody at risk.”

Joshua echoed the call for straightforward responses and integration of anti-racist work in every sphere of one’s life, especially the classroom.

PAC leader Kim spoke to the meaningful impact of reaching out to and empathizing with the Asian community around you.

“A lot of white people are just scared to overstep boundaries or to say the wrong thing and so they just don’t say anything at all. I think that that silence is actually worse,” Kim said. “Attempting to learn about another person’s experience and their perspective, even if you get it wrong, means that you’re putting in that effort and really trying to understand and that goes such a long way.”

Meyers added that the call to educate oneself and recognize prejudices is paired with the notion that there is work to be done beyond passive education. Her academic research focuses on racist comments made about Asian-Americans and the solution she found was simple: directly confront racism when you see it.

“What we find is that if people confront racism and they’re direct about it — so saying things like ‘Hey, that’s not okay, that’s really racist, you need to cut it out,’ anything that’s really direct, that is really the most effective way to combat those kinds of things,” Meyers said.