Out of balance together: Faculty juggle teaching and parenting

October 8, 2020

When asked how she is balancing teaching with parenting young kids, Associate Professor of English Kisha Lewellyn Schlegel’s response was simple: “There is no balance.”

“As I type this email, my daughter is barking like a dog,” she said. “In a bit, I’ll switch off with my husband, the poet Rob Schlegel, who also teaches at Whitman. We have repurposed the glassed-in front porch of our house to be our shared office (of sorts). I walk in as he walks out, and we ‘switch’ taking care of the kids, and, in passing, quickly ask: did you make lunch; did the teacher get back to you; do you still have that meeting; who’s on dinner?”

However, Schlegel is also aware of her family’s relatively privileged position.

“We are fortunate. It’s hard to work from home etc, but we have a home. We are working. We are not sick.”

Schlegel has a ten-year-old in fifth grade, a six-year-old in first grade, and a kitten who “attends no grade and refuses all teachers.” Her family’s experience captures a sense of frenzy shared by many Whitman faculty who are also parenting young kids.

Associate Professor of Politics Susanne Beechey described a similar parenting strategy. Her two boys are attending elementary school via synchronous Zoom sessions and asynchronous work times.

“The effect in our household has been one of a revolving door. My partner and I have set up a schedule for the fall semester that starts at 7:30 in the morning, and we basically just tag-team all day,” Beechey said. “The whole family is on this whirlwind schedule, everyone doing exactly the thing they need to do at the time they need to do it so that we can accomplish everything.”

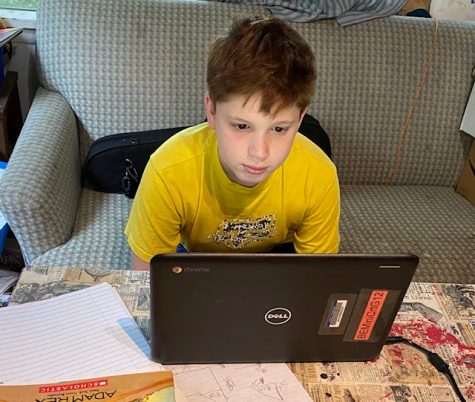

Professor of English Scott Elliott and Jenna Terry, Senior Adjunct Assistant Professor of English and General Studies, have sons in seventh and fifth grades. Even with teaching schedules that don’t significantly overlap, Elliott says there are sometimes three people streaming synchronous meetings at the same time, straining the Wi-Fi.

“We’ve learned the hard way not to use the microwave while anyone is in a class because it tends to crash our internet connection. I think students in one of my classes may have heard me yelling for one of the boys to stop using the microwave because the Zoom session had crashed,” Elliott said. “The helplessness of relying on Wi-Fi for a tenuous connection creates a low hum of anxiety that ends up taking a toll over time. Still, I’m impressed that it all works as well as it does, even as in every Zoom session there’s at least two or three times when someone’s sound cuts out or someone freezes when making their most important point, or simply disappears. I’ve never seen that happen in a classroom.”

“Even for these frustrating glitches, we’re all hungry for connections with others, and meeting online together to honor important subjects and to learn and figure out what we think through discussion is providing an energizing lifeline,” Elliott said.

For many, a strong community is a necessity for working and parenting during a pandemic.

“In this moment in which patterns and systems have been disrupted, our community has an opportunity to ask what is ‘community’? What does support look like? And what are the possibilities? So, this is a great time to read and address the 2019 Manifesta,” Schlegel said, referring to the document written by a group of Whitman’s women of color faculty last year.

Elliott mentioned informal faculty groups where parents can share their experiences and find support.

“The main strategy I would suggest,” he said, “is to cultivate a sense of humor and forgiveness in every direction.”

This theme of compassion was echoed by each of the professors interviewed. In particular, Schlegel disputed the existence of any sort of balance.

“At this point, the very concept of ‘balance’ seems so pre-pandemic. Like so many other tricks, it has been exposed as a false, unreachable concept, based on the notion that if we believe — if we just try! Hard enough, schedule! Hard enough — we too will FIND the BALANCE. It’s our fault if we don’t. Our failure is the only thing keeping us from getting there. It is another thing to achieve with excellence. It’s absurd,” Schlegel said. “But we are out of balance together.”

Beechey, who teaches gender studies classes, emphasized the gendered effects of the pandemic on working women with families.

“There is a disproportionate effect on female academics … in terms of juggling what we bizarrely call work-family balance in a moment where there is no balance,” Beechey said. “There is all kinds of evidence out there of steep drop-offs of women scholars being able to submit scholarship because they just simply don’t have the time.”

These national and international trends, according to Beechey, also cause concern about questions of tenure and promotion of faculty. Whitman has enacted some policies addressing this concern (such as allowing faculty to delay going up for tenure). However, these actions don’t address gendered societal expectations of an elusive work-family balance.

Compassion, frustration and humor all abound in the hectic lives of Whitman’s faculty parents. When asked about her kids’ school experiences, Schlegel reflected on the many lessons her kids are learning at home.

“Yes, [the kids] have a desk in their rooms, with a little lamp and pencils, where they sit and Zoom into class for 3 hours a day. But what are they learning from home? From this moment? We tried to teach them how to cook and empty the dishwasher but mostly they’ve learned how to use the remote. They’ve learned how much they love Avatar: The Last Airbender. They talk about it over dinner, while the adults sigh with ignorance,” Schlegel said. “We have no idea what’s going on. And they are learning that too. It’s great. They are learning how to be patient with adults. And each other. And with themselves. More than anything, I hope that they are learning what it means to be loved and to love and be present with each other in times of intense grief and disruption — a time that points us to the necessity of really being with each other. I’m learning with them.”