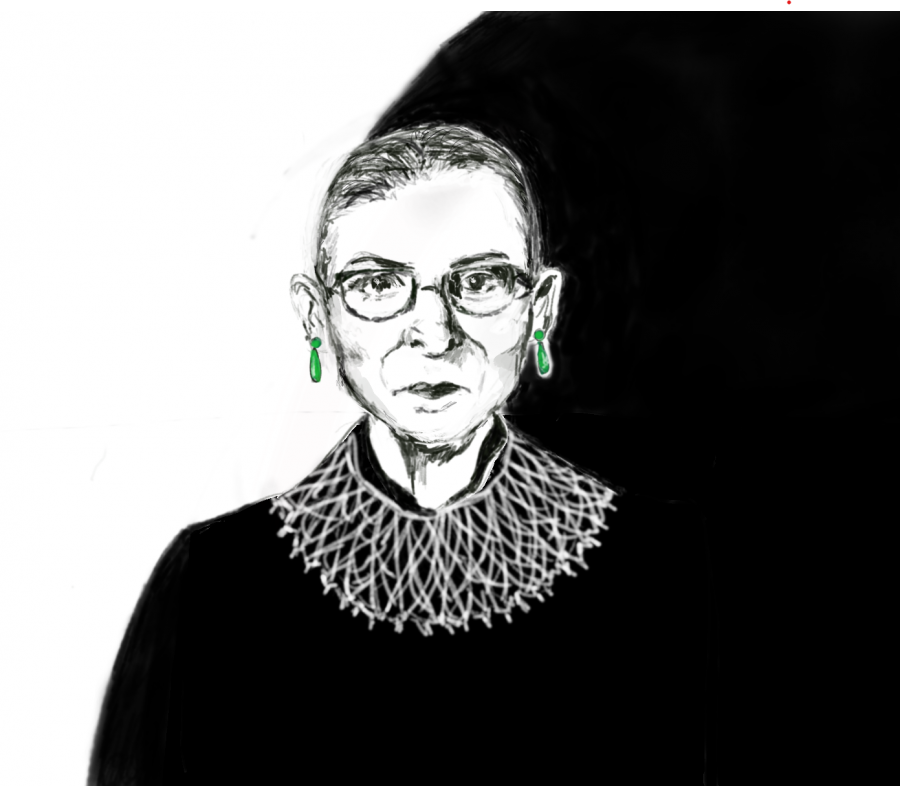

Whitman examines Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s impact

October 1, 2020

Since her passing on Sept. 18, Whitman community members have mourned the loss of Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg and re-examined her influence on American law, politics and the upcoming election. Justice Ginsburg passed at the age of 87 due to complications from pancreatic cancer.

Ginsburg became a lawyer in the 1960s when gender discrimination largely kept women out of law. Jack Jackson, an associate professor of politics, discussed the ways Justice Ginsburg brought about gender equality as a lawyer at the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) and co-founder of its Women’s Rights Project. During the 1970s, Ginsburg won a string of victories at the Supreme Court against laws that discriminated on the basis of gender.

“Ruth Bader Ginsburg played a pivotal role in enshrining gender equality in U.S. constitutional law,” Jackson said. “Prior to this period, the Court was quite deferential to legislative bodies using gender stereotypes in writing laws.”

Kaitlynne Jensen, a sophomore politics major from Milton-Freewater and president of Whitman’s Planned Parenthood Generation Action (PPGA), shared her appreciation for Justice Ginsburg.

“She was one of the only people on the Court that stuck by women’s rights every single time,” Jensen said. “One of the main things that [PPGA] is fighting for is for every woman to be able to choose for themselves whether or not they want to have a baby. RBG always fought for that choice to be left up to women whether that be through a woman’s right to easily accessibly birth control, or a woman’s right to have an abortion.”

As a justice on the Supreme Court, Justice Ginsburg dissented from a July 2020 decision that allowed employers to opt out of the Affordable Care Act’s birth control mandate for religious or moral reasons. This was one of many arguments in which Ginsburg pushed to expand reproductive rights.

Jensen shared how Justice Ginsburg was a role model for her as she grew up in a small rural town.

“Since she was able to overcome all of the obstacles of being only one of nine women in her class at Harvard and a female lawyer at that time, she gave me hope that I could also do great things even though I didn’t have as many of the resources as people from bigger cities,” Jensen said. “She was always a kind of beacon of hope.”

Claire Maurer, a senior politics major from Maine, is especially interested in the relationship between politics and law. Maurer was inspired by the way Justice Ginsburg intertwined these disciplines to make America’s laws more equitable.

“She employed the legitimacy of law and created better conditions for more people — not necessarily through shared beliefs or a system of hope in political rhetoric that you see in more legislative politics,” Maurer said.

While there are shifting power structures in Congress and the Executive Branch, Maurer argues that law provides the institutional backbone for American politics — and Justice Ginsburg advanced a more inclusive interpretation.

“[Ginsburg] simply employed an already existing structure of the law to more people,” Maurer said. “It was already there; she did not create anything.”

Maurer was referring to Ginsburg’s string of of landmark cases in the 1970s, in which Ginsburg successfully argued that the 14th amendment clause in the Constitution didn’t just bar racial discrimination, but discrimination on the basis of sex as well.

But amid the outpouring of love and admiration that followed the news of Justice Ginsburg’s death, questions bubbled up over her record on tribal law and what some of her critics call her history of “White Feminism.”

Notably, Justice Ginsburg wrote a 2005 majority opinion against the Oneida Indian Nation that argued their members’ land was not part of their reservation — and thus not tax-exempt — because it had been sold in the early 1800s and then later reacquired. Matthew Fletcher, Director of the Indigenous Law & Policy Center at Michigan State University and citizen of the Grand Traverse Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians, said Ginsburg’s language in the opinion was “incredibly dismissive of tribal prerogatives.” Fletcher blamed the Court’s collective lack of historical knowledge and its lack of pushback among the justices themselves. But, illustrating her inconsistent record on the issue of tribal law, Ginsburg voted with the majority in a landmark 2015 case that argued much of eastern Oklahoma is tribal land.

Ginsburg reportedly regretted her Oneida Indian Nation decision and had told colleagues she hoped President Trump would nominate a Native American woman to the Court.

The passing of Justice Ginsburg also has huge implications for the upcoming election on Nov. 3 and the weeks leading up to it.

Maurer believes the loss of an influential liberal power in the Court and the race to fill her seat has shifted the stakes of the election.

“When you see something that is as static as the Supreme Court up for a huge change, all of a sudden you’re seeing this discussion at the forefront of politics,” Maurer said. “I think you’re just seeing a total shift in what electoral politics is and an understanding of what electoral politics means.”

Jensen believes Justice Ginsburg’s passing may sway undecided voters to vote for candidate Biden because of the additional loss of liberal influence in the Court.

“I think for some people who were a little iffy on whether or not they were going to vote for Biden — so for people who were going to vote for third-party — I think [Ginsburg’s death] might draw them over,” Jensen said. “It might make them vote for Biden just because they might see how necessary it is to get someone who will actually be able to get Trump out of office into the office of the presidency.”

Last week, President Trump nominated conservative judge Amy Coney Barret to fill Ginsburg’s seat. The Republican-held Senate is expected to vote on her confirmation in mid-October.