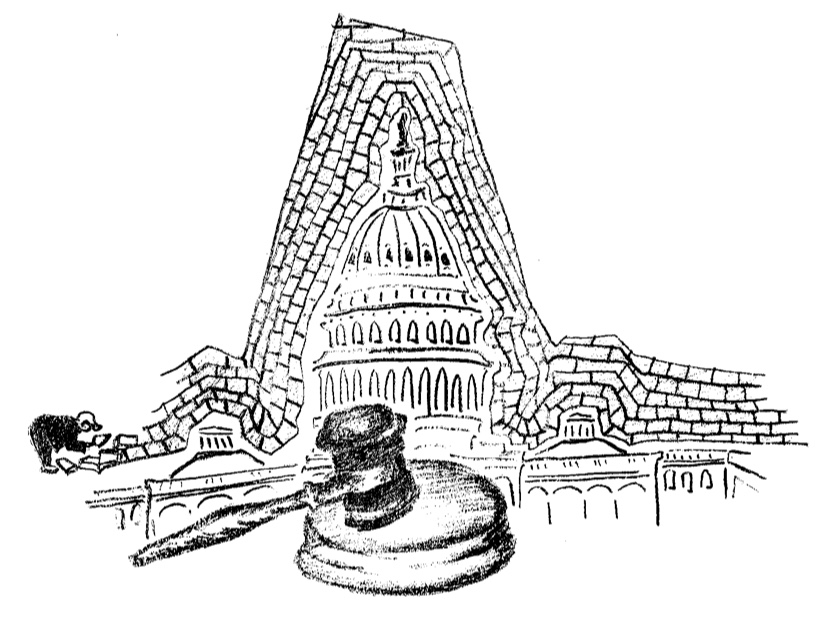

A National Emergency

February 26, 2019

President Trump declared a national emergency over the southern border on Feb. 15th, aiming to divert $6 billion from authorized projects to build his proposed wall. The announcement came after congress’ funding bill denied the president adequate wall money, sparking questions over the separation of powers and expanding executive authorities.

The house voted in favor of blocking the president’s national emergency on Tuesday, passing a resolution of disapproval by wide margin. The resolution will be brought to the senate floor in the coming weeks, where it needs at least four Republican defectors to reach a simple majority. If the resolution passes congress, the president tweeted he will “100 percent” block it with the first veto of his term.

Yet congress can still vote to block the emergency. A two-thirds majority in both chambers would pass a veto-proof overturn, but most Republicans, although uneasy, seem unwilling to sign support for the resolution.

Some Republicans have warned their colleagues to reject their leader’s declaration, fearing a dangerous precedent. Senator Thom Tillis, from North Carolina, bemoaned the declaration in an op-ed in The Washington Post.

“As a U.S. senator, I cannot justify providing the executive with more ways to bypass Congress,” Thillis said. “As a conservative, I cannot endorse a precedent that I know future left-wing presidents will exploit to advance radical policies that will erode economic and individual freedoms.”

The resolution’s backers are framing it as a referendum on the separation of powers, urging congress members to uphold their “exclusive powers of the purse,” as Speaker Pelosi put it, and reject the President’s attempts to circumvent congress to fund his campaign promise.

Some Americans see this as further evidence of the president’s authoritative impulses, worried he is eroding the legislature’s power for his own agenda. One founding father, according to Paul Apostolidis, a politics professor at Whitman, thought the best hedge against authoritarianism is a tricameral government.

“Madison’s contributions to the Federalist Papers stressed the need for there to be separation of powers to avoid the possibility of abusing governmental power, which he argued was more likely to happen if power were concentrated in one branch,” Apostolidis said.

President Trump’s desires are nothing new; many presidents before him tried to expand their influence.

“There has been a long-term trend since around the turn of the last century toward the executive gaining greater power vis-a-vis Congress,” Apostolidis said. This expansion continued with social programs like the New Deal, and military buildups like the World War Two mobilization, Vietnam and other Cold War projects, and post-9/11 initiatives, Apostolidis explained.

The powerful executive branch we know today is not what the founding fathers imagined. They foresaw the legislature’s fiduciary authorities granting it clout over the executive. The president though, acting as the steward of the nation, must be able to act quickly and unimpeded in the case of emergency.

“Hamilton argued emphatically in the Federalist Papers that the executive branch needed to have broadly discretionary authority to meet the imperatives posed by national emergencies, using the logic that those imperatives could never be predicted in advance,” Apostolidis said.

The National Emergencies Act uses similar logic, and gives the president broad discretion over what constitutes an emergency. What matters though, Charlie Savage, a writer for The New York Times, explains, is how the president came to declare this emergency.

“None of the times emergency powers have been invoked since 1976, the year Congress enacted the National Emergencies Act, involved a president making an end run around lawmakers to spend money on a project they had decided against funding,” Savage said in an article. “Mr. Trump, by contrast, is challenging the bedrock principle that the legislative branch controls the government’s purse.”

This is the basis of a lawsuit, filed by a coalition of 16 states, to block the national emergency. It questions whether the president has the power to redirect funds appropriated by Congress, as well as the statutes used and the validity of the emergency.

Many believe in emergency powers when necessary, but feel this emergency is fabricated and dishonest. Nadyieli Gonzalez Ortiz, a second-year politics major from Banderas Bay, Mexico, is one of them.

“I think there’s definitely a need for powerful moves in politics to change real problems,” she said, “but it’s also scary to think those same tools and laws can be used to do something like this wall.”

Congress is not expected to pass a veto-proof resolution, so the onerous is on the courts to block the president’s emergency. The states’ lawsuit will make a slow march through federal courts and might, as the president expects, reach the Supreme Court. There, the president hopes his two judicial picks will help uphold his declaration of emergency.