Dunnivant Releases New Book

“Environmental Success Stories” latest in faculty publishing

April 6, 2017

This March, Whitman chemistry professor Frank Dunnivant published a book on success stories in the environmental movement since the 1970s. It is the most recent book published by a Whitman faculty member, and the second in 2017.

“Environmental Success Stories: Solving Major Ecological Problems and Confronting Climate Change” looks into a number of cases in which an environmental problem, such as anthropogenic lead or unsafe drinking water, was identified and addressed. One common denominator: governmental regulation.

Dunnivant recalled a hallways conversation in 2004 about the failures of the Bush administration in attempts to truly dismantle the environmental regulatory structure. He was struck by the distance the environmental movement has come, the battles it has won, despite the “doom and gloom” rhetoric that pervades the contemporary environmental movement in regards to major challenges like climate change.

Dunnivant said the original plan was to emulate the structure of “The Botany of Desire,” by Michael Pollan, that tells its story via the cases of four plants. But as his research developed, Dunnivant said he “was amazed at how many more chapters there were. How many more stories there were to tell … it turned into six or eight really quickly. And there’s more.”

The book is intended both for the classroom and the popular science reader. The introduction says that the “book shows, case by case, what can be accomplished when citizens, governments and industry work together.” “Environmental Success Stories” is, of course, rooted in scientific research, but the emerging message is political: “if your politicians cannot be educated or do not believe in science, then vote them out of office.”

Despite the uplifting title, the idea, said Dunnivant, is not that the rhetoric of “doom and gloom” is wrong, but that it’s unproductively fatalistic despite the fact that we have a tries and true method of success.

“The only way we’re gonna solve climate change,” Dunnivant said, “is global regulation, which everybody in the world agrees with except us, except our GOP politicians … The GOP doesn’t like to believe in science. And the reason is, if you believe in science you have to regulate. If the free market solves this, all of those doom and gloom books are gonna come true.”

Dunnivant has been outlining this book since that hallways conversation, and he began writing in earnest four years ago. His last sabbatical was largely dedicated to the writing of the book.

Dean of Faculty Alzada Tipton wrote in an email to The Wire that Whitman’s unusually generous sabbatical program (faculty at Whitman may go on sabbatical every two and a half years) allows for a “higher degree of scholarly activity here than at many liberal arts colleges … I would say that one hallmark of Whitman faculty’s emphasis on scholarship is how much they involve students in their scholarship.”

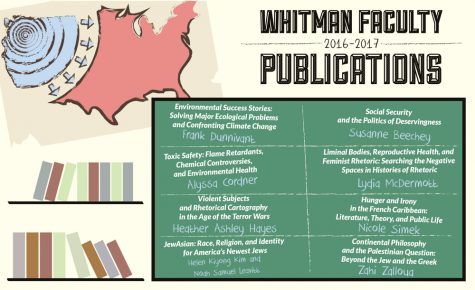

Numerous faculty books have been published in the last year. Heather Hayes wrote “Violent Subjects and Rhetorical Cartography in the Age of the Terror.” Alyssa Cordner wrote “Toxic Safety: Flame Retardants, Chemical Controversies, and Environmental Health.” Nicole Simek wrote “Hunger and Irony in the French Caribbean: Literature, Theory, and Public Life.” In all eight, Whitman faculty have published books between the beginning of 2016 and now. French Literature professor Zahi Zalloua’s “Continental Philosophy and the Palestinian Question: Beyond the Jew and the Greek,” was the first of 2017 (scholarly articles are not counted).

The academy, particularly in the scientific realm, is notorious for its distance from public life.

“Scientists sit in their lab and do their research,and you know I think my most prominent paper, 150 people read,” Dunnivant said. “We don’t touch a lot of people with our research in our lab. The people that influenced me to be a scientist were Rachel Carson, [Louis] Leakey, as a child reading this and thinking, ‘Wow I would love to do something like that.’

“And that,” Dunnivant continued, “is a … void right now in popular science. Scientists need to be more involved with the population. Otherwise we’re these geeks in our ivory towers that nobody can understand.”