Capital Punishment on Trial

A bill in Olympia aims to ban the death penalty in Washington State, once and for all.

February 16, 2017

In January 2017, Washington State Governor Jay Inslee and Attorney General Bob Ferguson introduced Senate Bill 5354 to end the death penalty in Washington State. In a press conference, Inslee said, “the evidence is absolutely clear that death penalty sentences are unequally applied, they are frequently overturned, and they are always costly.”

The Senate Bill comes three years after Governor Inslee ordered a statewide moratorium on the death penalty. The moratorium suspended the executions of all individuals on death row and served to call attention to what Inslee called an “imperfect system.”

Twelve state senators have pledged their support for the bipartisan bill, including Representative Maureen Walsh-R of Walla Walla’s 16th District. The local Washington State Penitentiary in Walsh’s district is the only facility in the state with an execution chamber and one of two facilities in the US with an active gallows.

“As a means of effective punishment, the death penalty is outdated,” Representative Walsh said.

Republican State Senator Mike Padden, who is opposed to the bill, told one Seattle Times reporter, “I’m not a zealot for the death penalty … but I do think there are some heinous crimes where it should be on the table.”

The debate over capital punishment has deep roots in the state. Washington’s death penalty has been abolished–and restored–twice in state history: first in 1913, when a Seattle representative named Frank P. Goss passed a bill to eliminate it, and again after a U.S. Supreme Court ruling in 1972 maintained that capital punishment was unconstitutional. Washington reinstated the death penalty in 1976 after amending its sentencing procedures to include a bifurcated trial process in which the same jury determines guilt first and punishment second. To be a juror in a murder trial in Washington, a person must tell the court that he or she is comfortable imposing the death penalty. Though this arrangement attempts to ensure that juries across the state will be consistent in their decisions, it necessarily excludes citizens who cannot condone capital punishment.

“You create a system that is self-fulfilling if you won’t let people sit on juries who don’t believe in the death penalty,” Heather Hayes, Chair and Assistant Professor of Rhetoric Studies at Whitman College, said.

—

Around ten o’clock on the night of January 4, 1993, Timothy Kaufman-Osborn stood outside the Washington State Penitentiary in Walla Walla. A little after midnight on January 5, Westley Allan Dodd would face the death penalty on three counts of aggravated first-degree murder. Not only would Dodd’s execution be the first in Washington State in 27 years, but it would also be the first legal hanging in the United States since 1965.

Kaufman-Osborn, the Baker Ferguson Professor of Politics and Leadership at Whitman College, was one of 12 people to show up in opposition to the death penalty on the night of Dodd’s execution. Over 200 people were present to support it. Kaufman-Osborn remembers seeing a sign saying, “What the Heck, Stretch His Neck.”

Some people brought miniature nooses. At midnight, somebody in the crowd popped the cork of a champagne bottle.

“On the one hand I was horrified by the spectacle,” Professor Kaufman-Osborn said. “On the other hand, as a good academic, I was fascinated by it. I had never studied capital punishment as an academic area of inquiry.”

Dodd’s execution threw Kaufman-Osborn into activism. While teaching at Whitman, he published a book on the politics of the death penalty titled From Noose To Needle: Capital Punishment and the Late Liberal State. He also became a vocal member of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), an organization which advocates for the abolition of the death penalty nationwide. Washington is one of 31 states in the country that implements the death penalty, but 2017 just may be the year the state abolishes death row.

—

Timothy Kaufman-Osborn has focused most of his research on the unequal application of death sentences in Washington state. Kaufman-Osborn likened capital punishment to “a rigged lottery”–not all offenders are treated equally. As an example, in 2003, Gary Ridgway (often called the “Green River Killer”) pled guilty to 48 counts of aggravated first-degree murder. Despite being the most prolific serial murderer in state history, Ridgway struck a plea deal with the King County prosecutor and was spared a death sentence in exchange for helping law enforcement officers locate the bodies of 41 missing victims. “So you’ve got arguably the most heinous murderer in Washington State…who will live out the rest of his life in a cell,” Kaufman-Osborn said, “whereas if you look at the number of victims of those who remain on death row now…the body count is considerably lower.”

—

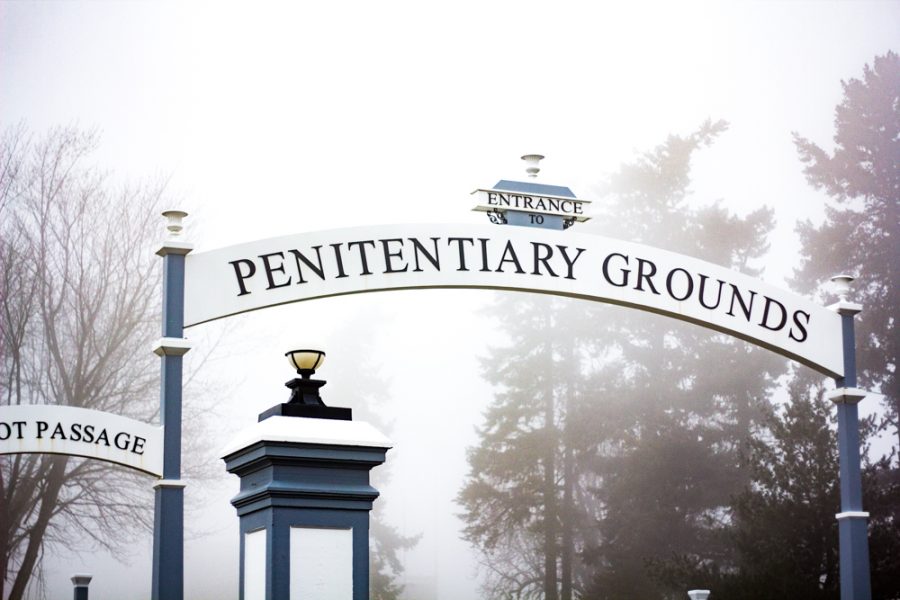

A glimpse into the grounds of the Penitentiary.

The exorbitant cost of death sentencing compounds the issue of unequal application. A 2015 Seattle University study found that, on average, a death penalty sentence costs the state $1 million more than a sentence to life without parole.

“Capital cases are tremendously expensive to conduct, especially as you go through the whole appeals process,” Kaufman-Osborn said.

He noted that, because of the high expense, prosecutors in eastern counties are less likely to pursue capital punishment than their wealthier Western counterparts, “not because they think it should not be sought but because they realize it is going to gut the coffers of county governments.”

Of the 78 men executed in the state of Washington since 1904, only 22 have come from counties east of the Cascades.

Data also suggests that in interracial homicides nationwide, black offenders with white victims are ten times more likely to be sentenced to death than white offenders whose victims are black. “If we can demonstrate the system is classist, racist–for which there are just reams of evidence–how can that possibly be just?” Kaufman-Osborn said.

—

Scott Odem worked as a law enforcement officer in Walla Walla for 25 years. He is now a Classifications Officer working with minimum security inmates at the Washington State Penitentiary.

“I’ve seen personally what human beings can do to one another,” he said.

Odem understands why many people believe the death penalty is fair punishment for heinous crimes.

“I’ve seen the victims in that condition and … [there are] a lot of emotions that start swirling around,” Odem said.

Professor Hayes agreed that the main argument for the death penalty is retributive.

“People that support the death penalty…[use] purely a punitive rhetoric,” she said.

According to Hayes, the prevailing sentiment among death penalty defenders is that the crimes committed by inmates on death row are “so awful they don’t deserve to continue to live among us.”

—

“The anti-death-penalty sentiment now is greater than it has been,” said Keith Farrington, Professor of Sociology and The Laura and Carl Peterson Endowed Chair of Social Science at Whitman College.

But, Farrington wrote in an email, “it is still the case that the majority of Americans nationally support the use of the death penalty capital as an appropriate penalty for certain kinds of criminal murder conviction.” Bill 5354 is currently in Senate committee. It has a long way to go.