Rock Bottom: Why is Whitman Not Financially Accessible?

This article is the centerpiece of a series of Pioneer articles on Whitman’s financial aid policies published this week. For more, read about the college’s financial and merit aid history, surprising ways Whitman could meet 100 percent of need, and what ‘accessibility’ means.

Rock bottom. That was Whitman’s place for the second year in a row on the Financial Accessibility Index. The index, which measure how well colleges support low-income students, was published by The New York Times in September. Last year, Whitman came in last of the 100 schools on the list. This time around, it was 153 on an expanded list of 179 schools.

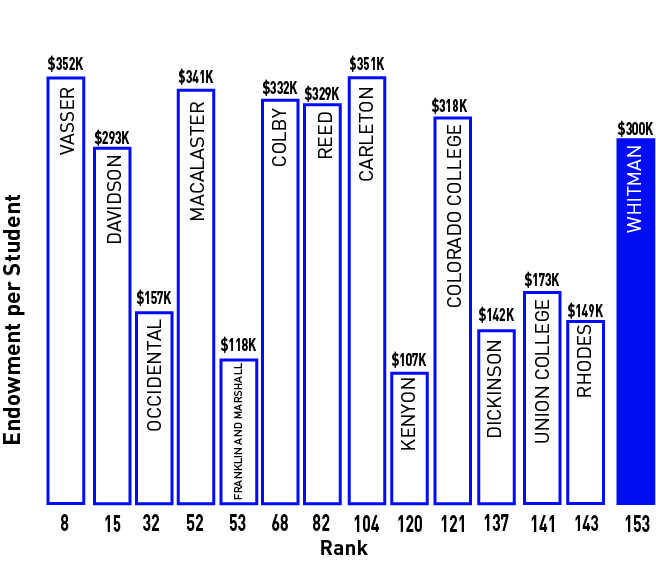

Whitman’s endowment is strong and has grown significantly in recent years. So why does the college continue to struggle to provide access to middle- and low-income students? Despite having over 300k dollars in endowment per student, Whitman performed worse than any of its 12 comparison schools. No school below Whitman on the list has over 200k dollars per student, and 88 schools with smaller endowments per student ranked above Whitman.

While Whitman’s place in the higher education market limits its options, a number of decisions have led it to the point it is now. Merit aid, direct giving from alumni towards the endowment instead of annual costs and the distribution of spending on financial aid and other costs all contribute to the college’s inaccessibility problem.

Financial aid policies

Under its current financial aid policies, Whitman can reject applicants based on their family’s lack of wealth. As opposed to being “need-blind,” this “need-sensitive” position allows the college to evaluate a student’s financial need as part of the process in admitting them.

The other key piece to a college’s financial aid policy is the percentage of demonstrated need met. While Whitman has consistently met between 91 and 96 percent of demonstrated need in the past 10 years, the significant majority of the college’s comparison schools meet 100 percent. For the class that entered in 2013, the most recent publicly available data, Whitman met an average of 92.9 percent of student need.

Why does Whitman spend so much on merit aid?

Whitman gives a greater percentage of its financial aid budget to merit aid than all but one of its peer colleges. In 2013-14, over 17 percent of Whitman’s financial aid went to students who had no demonstrated financial need, while this number was under nine percent for most of its comparison schools. If Whitman were to give a third of its merit aid funding to need-based aid, it could meet 100 percent of need.

Unfortunately, solving Whitman’s accessibility problem isn’t that simple. Tuition from wealthy students who receive merit aid makes up a large portion of Whitman’s budget, and merit aid is often a deciding factor when these students decide which school to attend.

Other liberal arts colleges in Oregon and Washington— including the University of Puget Sound, Willamette and Lewis & Clark— offer large merit packages to attract these same students. According to Dean of Admissions and Financial Aid Tony Cabasco, this competitive aspect, combined with Whitman’s somewhat isolated location, cause the college to offer significant merit scholarships to students who don’t qualify for need-based aid.

“Our overlap Pacific Northwest colleges give more in merit,” he said. “If we did not need to spend the merit-based aid money to get those students to come, we wouldn’t have to. But that’s where we stand.”

Although it continues to spend more than other schools, Whitman has been lowering the percentage of financial aid going to students without need over the last decade. According to Cabasco, as the college’s reputation and “place in the market” of its peer colleges has risen, fewer wealthy students have needed merit aid to entice them.

“How you use merit aid corresponds to your position in the marketplace. Some colleges can draw and enroll students without significant merit aid. Others like Whitman need to use more of that,” he said. “It’s hard to get kids to come to Walla Walla, that’s the reality.”

President Kathy Murray, who was previously the Provost and Dean at Macalester College (which ranked much higher on the New York Times list at 52) said that both colleges operate with similar strategies in mind. Where institutions vary is in the amount they award.

“Macalester and most of our peers use merit aid in very similar ways, and that’s to increase yield of students who can pay a significant portion of the tuition,” she said. “The dollars that come in from those students help us to be able to fund the students with higher need. It’s the reality of the [college] marketplace at this point.”

Merit aid’s gamble: The class of 2019

Does Whitman run the risk of throwing merit awards at students who may not need to be won over? Cabasco said it’s a possibility, and part of the balance his office strives for in making the college accessible.

“That’s one of the challenges we have: to make sure we set the proper amounts. You don’t want to spend too much [on merit aid], and you don’t want to spend too little.”

This challenge came into focus with the class that entered this fall. Whitman did not raise the amount offered in merit scholarships, unlike many other Pacific Northwest colleges. Harvey and Cabasco believe this is the reason the incoming class fell short of its enrollment goal by 30 students, as wealthy students chose to attend other schools.

Though this year’s class has more socioeconomic diversity than previous years with more first-generation and Pell Grant students, the college is currently facing a budget shortfall. As a result, merit aid will likely increase next year, and is unlikely to end in the near future.

“We did better in yielding students who had financial need … But [what happened this year] is not sustainable,” said Cabasco, referring to the budget deficit. “You either need to increase revenue or cut expenditures to make it work.”

How does percentage of need-met fit in? Cabasco said the college’s current gap would be the first priority if more money was made available to need-based aid.

“It would take about 1.2 million dollars, today, to meet the demonstrated need of everyone who is here at Whitman,” he said. “My sense would be, given that our approach has been ‘let’s do a better job of taking care of our students who are already here,’ [we would meet 100 percent of need] before we expand the socio-economic numbers.”

Where are the gifts going?

Redistributing funding is not the only way the college could find the funds needed to meet 100 percent of demonstrated. If the college were able to increase its overall income by two percent, it could also reach its goal. Funding comes primarily from three places: program service revenue, the endowment and annual gifts from alumni.

Program service revenue includes net tuition, room & board and bookstore profits; in other words, what students and their families pay every year. At Whitman, these costs usually pay for about 78 percent of total expenses, compared to 70 percent of total expenses at schools with similar endowments. Because Whitman has the same policy regarding its endowment as these schools, the difference likely comes from the amount of annual giving.

According to John Bogley, Whitman’s Vice President for Development & Alumni Relations, Whitman receives a similar amount in gifts from alumni every year as its comparison schools. It is difficult to determine how each of these schools spends their gifts. However, according to Harvey, other schools generally have two to three times as much unrestricted giving, money that is not donated for a specific purpose and the college can spend however it feels best.

While direct statistics are not available, evidence suggests Whitman differs from other schools in that more gifts from alumni tend to go into the endowment or be contributed for specific purposes, and fewer are available for unrestricted use in the year they are given.

“That’s a strategy we consider at times: should we try to raise the amount of gifts coming in? There’s a balancing act between how much you spend immediately, and how much you invest in the endowment to have long-term sustainability,” said Whitman’s Treasurer and Chief Financial Officer Peter Harvey.

Giving is influenced both by what the college requests and what alumni are predisposed to give to. If it choses, the college could ask alumni to contribute gifts to use for meeting 100 percent of need in the year it is given. This would make meeting 100 percent need easier, but slow the rate of growth of the college’s endowment.

Why can’t the endowment help?

Whitman’s endowment provides for the long-term financial stability of the college. In the last five years, it has grown rapidly due to successful investments and the concentration of alumni donations.

Most colleges, including Whitman, take five percent of their endowment every year to pay for annual costs. To keep the endowment steady, Whitman calculates the endowment’s average value in the last three years. It then spends five percent of this number on the budget, and assumes there will be two percent inflation. For the last decade, the average college endowment grown seven percent a year.

“In theory you can [spend more every year], but I don’t recommend it. The purpose of the endowment is to exist in perpetuity, it’s to make sure it provides the same level of support to students today as it is to students in ten years from now, twenty years from now, fifty years from now,” said Harvey.

To meet 100 percent of need, Whitman would need to spend less than half a percentage more each year. However, administrators are reluctant to do this as it could risk the college’s financial future.

Whitman cannot spend all revenue from its endowment as it likes. Oftentimes, donors specify a use when they give to the college. One third of the revenue from the endowment is specifically committed to financial aid. Another third is unrestricted; right now, this is entirely committed to financial aid as well. The last third was donated for instruction, academic support, the physical plants and other uses.

Whitman recently raised 165 million dollars for the endowment and other projects through the Now is the Time campaign. Not all this money is available today, as a portion is in the form of pledges which will be paid over five years, and in estates which will be given to the college when alumni pass away. However, of the 50 million dollars raised for financial aid, 35 million dollars are in use today, and much more is available from unrestricted funds raised by Now is the Time.

In the most recent year, it would have taken only 1.2 million dollars to meet 100 percent of financial need for students. If the endowment had 24 million more dollars committed to financial aid last year, the revenue from this addition could have covered this difference. Despite the endowment’s rapid growth, it has not been able to meet 100 percent need in recent years. However, depending on its financial decisions in the future, it may one day reach this goal.

The future of financial aid

Data from colleges is usually released two years after the year it refers to. Changes Whitman made following its poor performance on the College Accessibility Index last year will only begin to be seen next year. It is likely that Whitman’s rank will improve, though this is not guaranteed as other colleges may have improved accessibility as well.

However, no permanent policy changes have taken place. Most of Whitman’s peer schools meet 100 percent of need for the students they admit; while everything has a trade-off, there are a number of areas where Whitman could divert or raise funds to apply this policy. It could trim merit-aid and other areas of the budget, raise tuition, redirect alumni giving or take advantage of the larger endowment.

Financial accessibility is likely to be one of the topics discussed when President Murray heads a committee to form a Strategic Action Plan next year.

“I am a product of significant financial aid as an undergraduate. I was given access as a student who could not possibly afford to go to the institution I went to, so for me this is a really important piece. But I also have a responsibility to make sure the budget balances,” said Murray. “We will absolutely be thinking about this during the strategic planning process.”

This article is the centerpiece of a series of Pioneer articles on Whitman’s financial aid policies published this week. For more, read about the college’s financial and merit aid history, surprising ways Whitman could meet 100 percent of need, and what ‘accessibility’ means.

Noah • Oct 28, 2015 at 5:20 pm

You should check out the public tax returns for whitman college. It is pretty astounding how much money the school generates yet still argues in favor of putting a focus on admitting wealthy students. There seem to be many places the school could pool money together from in order to open access to more financially diverse students and not just the financially elite. One example is the amount of money given to the board of trustees for compensation. The board members are given over $100,000 a year for “1 hour/week”. Many, if not all, of the board members are already hugely wealthy from running large businesses. Their combined salary alone could have easily made up the $1.2 million gap to meet all need last year.

Steve • Nov 3, 2015 at 12:32 pm

The board members aren’t paid a penny – they even pay their own travel costs to attend meetings and functions. And in fact, they are some of the largest current donors to the college. Where did you get your $100k number? Look at Whitman’s 990 – it’s on their website. It clearly shows zero compensation for board members.