Penmanship Lost

Our modern relationship with long-form handwriting

December 5, 2017

Doctor’s handwriting is famously difficult to understand. Deepraj Pawar (‘19) is in the middle of interviewing for medical school, and she says that, “I’ve had some internships/volunteer positions where the hardest part is reading their writing, which is tough when you’re entering a patient’s medication into their charts or something because you want to make sure you’re being accurate.” Given the importance of clearly understanding a doctor’s instructions, the messiness of their handwriting is surprising. To a doctor, the ultimate function of writing is the effective communication of raw information. Expression of sentiment, or personal feeling is minimized. Says Pawar, “In medicine I think handwriting’s role in conveying emotion is minimal.” Pawar raises an important point, explaining that writing, or information on paper, should only serve to introduce a more important one-on-one encounter. She explains, “I think the ratio of time the patient spends talking to the physician vs the amount of time they spend looking at the physician’s handwriting makes it so the physician-patient encounter will set the emotional tone for an encounter, rather than their handwriting.”

Not so long ago, handwriting was an extremely intimate form of communication, used almost universally to express emotion. Autograph books, instead of yearbooks were popular in high schools up until the early 20th century. Students would trade autograph books, and write long, beautifully expressive notes to one another in their best cursive. This same principle resonates today: receiving a handwritten letter in the mail is a special feeling. It shows that the sender of the letter made time and put in effort to write a more heartfelt message.

For the first time, the 2009 Common Core standards, adopted by most states, do not require that cursive be taught to elementary school students. Given the growing prominence of computers in the education system, this trend is hardly surprising. As of 2012, computers are used in 95% of US educational institutions, and the number of computers found in schools has increased by 71% since 1999.

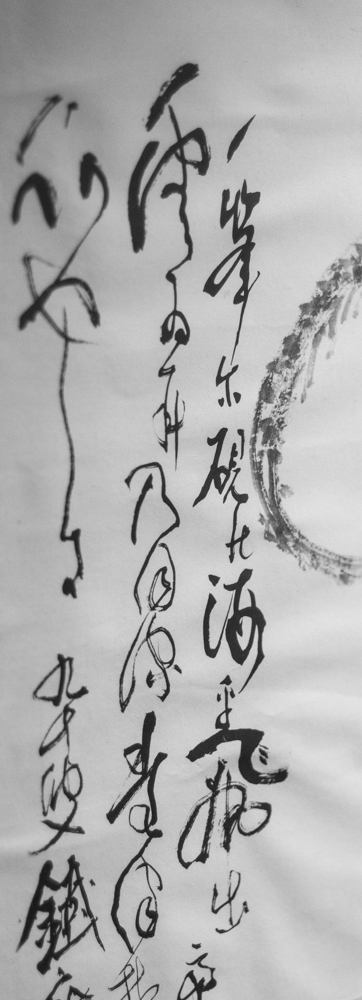

Prof. Akira Takemoto, Japanese Language and Culture instructor at Whitman, as well as calligraphy practitioner, says that writing should be a creative process. One style doesn’t suit everybody. “Writing,” he says, “should be about the journey, rather than the destination.”

To some, writing by hand is a more natural form of communication. Prof. David Schmitz, History Department Chair at Whitman says that he prefers writing by hand to computers, because the process is much more natural and comfortable. When he’s writing out lecture outlines, or even manuscripts for his books, there is no pause between his thoughts, and his ability to express those thoughts with a pen and paper. Schmitz explains, “To me, the reason I still handwrite so much is that it allows me to think and concentrate better than looking at a computer screen, maybe because I’ve been doing it my whole life. Having the pen and paper in my hand, I don’t think about the process it’s so natural to me.” Computers, on the other hand, require an additional step in the writing process. Typing on a computer requires conformity to a certain set of parameters. It is not easy to quickly switch between locations on the page, write quick notes in the margins, or write with different sizes while typing. Schmitz says, “When I’m typing, even though I type hundreds of words a day, there’s still a mechanical part of it that’s not as natural. Writing’s a form of thinking, and you know, if I concentrate your mind I can just move the pen anywhere I want or make a sidebar, reach over and grab a piece of scrap paper and jot something down. There’s a continuity to the process that works for me.”

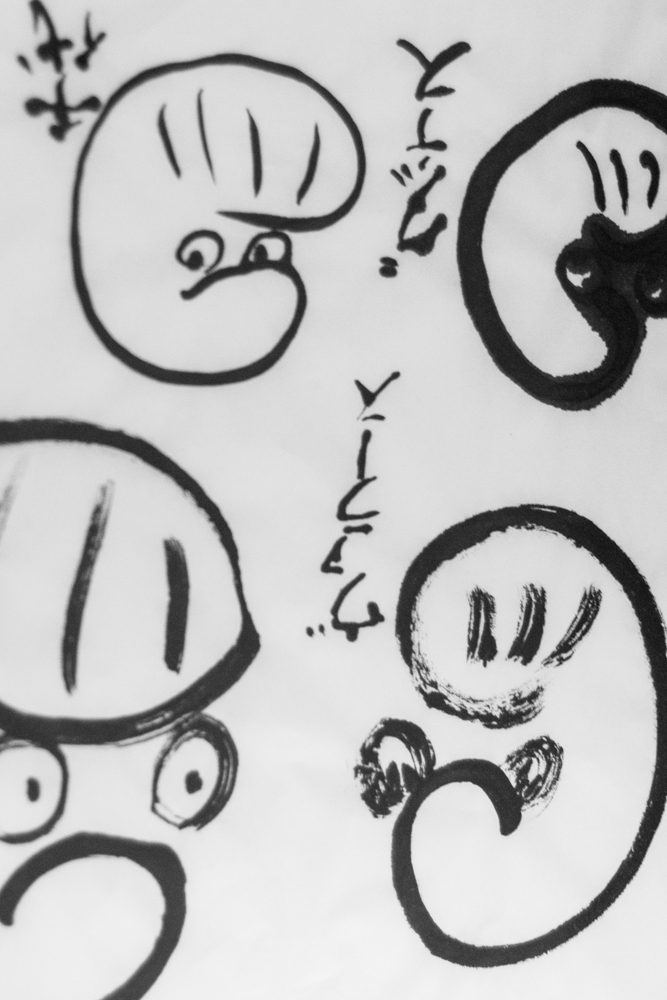

Writing can also take the form of a creative, constructive exercise. Amy Zhang (‘19) spent most of her early years in China, until age 14. As a child, she learned to write both English and Chinese characters. Writing in Chinese, she explains, is a much more creative process than English. She shows me the character for ‘apple.’ She points to different symbols in the character, each one representing a related concept, a constituent part of ‘apple’ as a higher level concept. Says Zhang, “Each character means something. It’s kind of like a puzzle. Each word has a character that means something, and you add on with another word or character and it means something different. There can be a story behind a word.”