Examining the Past through Whitman’s Own “Scenes and Types”

May 17, 2016

While listening to a RadioLab podcast the other day I learned something startling: every single memory we have has been, to varying degrees, embellished, altered, and and reconstructed. There is no such thing as an wholly honest memory, and, ironically, the more we recall something the further it diverges from the truth as we reinterpret it over and over again, tweaking a detail here, changing an impression there. The culminating paradox of memory, presented by Israeli scientist Yadin Dudai twenty minutes into the podcast, is this: “The safest memories are in the brains of the people can’t remember.”

What does that mean for those of us who do remember–who, if given the choice, would choose to keep on remembering, even while knowing our most private recollections will grow increasingly dishonest? Our first kiss, family holidays, the most beautiful sunset, the best day of our lives– none of these things are safe from the forces of memory.

The collective memory of a nation, a region, or an institution like Whitman College is subject to the same sorts of dishonesties and distortions as the individual mind. Because those in a position of power gain a monopoly on storytelling, they imprint the collective memory with their own interpretations, biases, and false memories, leaving little room for the perspectives of subordinate groups.

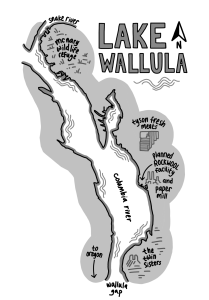

At Whitman, such storytellers include settlers who referred to “that region lying west of the Rocky Mountains and between Mexican California and Russian Alaska” as “No Man’s Land” in one breath and yet spoke about the “wild tribes of Indians” who inhabited the area in the next. Waiilatpu, where the Whitmans founded their mission, was “the cradle of Pacific Northwest history.” Yet the Cayuse, Nez Perce, and other tribes had been living there and creating history long before white people arrived. The narratives created by the colonialist writers of Walla Walla and Whitman history remind us that it is too easy to fall into the trap of explaining away one’s actions with spiritual conviction, charitable intentions, and lofty concepts like “Manifest Destiny.”

Recent developments reflect the desire for a more critical examination of Whitman’s history. The campus newspaper “The Pioneer” un-named itself in order to find a moniker that better reflect its goals and values as a student newspaper, and several weeks ago President Murray announced the removal of Whitman’s mascot, the missionary, a change that comes after decades of dispute and with the support of a majority of current students and faculty. The Indigenous People’s Education and Culture Club (IPECC) circulated a petition to modify first-year orientation to include a visit to the historic Whitman Mission as well as the Tamástslikt Cultural Institute to broaden students’ understanding of Whitman’s history.

Too often the past is reduced to a cast of “good” versus “bad” characters, whether it’s the savage Indians v. the virtuous God-sent pioneers or the evil colonialists v. the infallible Native Americans. This is not to excuse or minimize the blatant wrongness of violent acts of colonialism committed by white people. It is only to remind us that such black-and-white views of history ignore the more nuanced realities and complicated motives of groups of people. When one reduces the oppressor or the oppressed into a single “type,” one loses an opportunity to gain a richer understanding of the past that may help prevent such violent acts in the future. So how do we achieve a more nuanced understanding? One way is through visual objects. That’s where the photography of Adnan Charara (and of Whitman’s own archives) comes in.

From January 29-April 14 Whitman’s Sheehan gallery hosted the exhibit “Scenes and Types: Photography from the Collection of Adnan Charara.” The exhibit revolved around the concept of ‘Orientalism,’ defined as the typecasting of people from Asia, Africa, and the Middle East by western photographers (and in some cases by indigenous photographers themselves) in the 19th century. Highly staged photographs crammed people into narrow roles in order to satisfy Western notions of ‘the Orient,’ including “types” such as the erotic slave girl, the demure and sensual dancer, the mystical sage, etc.

One of my favorite components of the exhibit were the stacks of postcard-like reproductions of the same ‘Orientalist’ photographs that hung on the walls of the exhibit. From among the piles of images (free for the taking) one could choose the bare-breasted young woman, her chest and wrists adorned with jewelry, a coy smile playing across her face; if one had more modest tastes one could choose the woman veiled in black, covered head-to-toe except for one hand that is pulling closed the head covering, out of which a single eye peers at the viewer.

As I set out to take several images for myself, I had a sudden and unsettling question. How does one go about selecting postcards of racist depictions of people? Well, one feels uncomfortable, though certainly that is (part of) the point. My choices were based on striking colors, poses, or especially intriguing facial expressions of the subjects–probably some of the very same aspects that would influence a nineteenth century collector. What does one do with a stack of racist postcards? One sticks them in one’s desk drawer for about two months because, as it happens, one doesn’t know one should do with them.

Clearly these postcards were meant to prompt questioning about our position as viewers. How are we in the twenty first century any different than the European and American audiences in the nineteenth century who also viewed and collected these same images? Do our more enlightened intentions in viewing the photos make our viewing any more excusable? I believe Whitman student Margaret Rockey put it best in her note to Mr. Charara on the back of one of the postcards, a portion of which is reproduced here:

“Yes, Orientalist photographers intended to order, know and dominate the Other when they set out in the “Orient,” but perhaps there was also a sincere, if misguided, effort to form genuine cross-cultural connections and understanding, goals not so dissimilar from the liberal arts’ curriculum. These “bad” and “good” intentions are not mutually exclusive, just as my enjoyment of the photos occurred simultaneously with my abhorrence of their racism. Perhaps this exhibition is an opportunity not only to critique nineteenth-century Orientalists’ unflinching certainty in their own knowledge of other people and places, but to reconsider our own trust in our intentions and knowledge.”

How does Whitman’s history reflect the same tendencies to “order, know and dominate the Other”? For Whitman to critically examine its past requires confronting the names, symbols, images and stories handed down by the past. In the spirit of examination, uncertainty, and honest self-questioning, I present a few photographs, Whitman’s own ‘Scenes and Types.’ These photos were pulled from Whitman’s archives, a receptacle much closer to home than Asia, Africa, or the Middle East. They depict Native Americans, probably from the Walla Walla area, though even that is uncertain.

I submit these photos as reminders. They are articles of re-memory that, like Charara’s photos, contain many more questions than answers. They invite us to not just look passively but rather to ‘re-remember’ them with a critical mindset. As the RadioLab podcast says, memory is a tricky thing. While it is inevitable that we distort the past, let us try to combat the opposite of memory–forgetting–with the visual reminders left by those who came before. We do this not to glorify or disparage those people, but to remind us that the past still exists– in our archives, in our memories, and in the stories that live all around us. What did I end up doing with that stack of racist postcards from the Charara exhibit? I took them out of my drawer and looked at them. We need to critique and engage these objects of re-memory so that we take more care to be honest in crafting our own stories, the memories of future generations.