Every night, millions of protectors watch over gardens of lettuce and turnips. Without them, our crops would be overrun by pestilence and drought; and yet, we don’t offer them a word of thanks. Most of us don’t even spare them a single thought, despite our rich history with their species. I am, of course, referring to lawn gnomes.

Gnomes were domesticated somewhere between 40,000 B.C. and the 1800s. Before we took them in and gave them little hats, they were foragers. They survived on an insect and fruit diet and lived in groups of three or more. Their natural inclination towards assuming cute poses and staring at vegetable patches made them ideal for domestication.

We bred them for softer beards, better plant identification and higher prey drives. Gnomes were also highly adaptable; some could even be kept as indoor pets for European nobility. If dogs are man’s best friend, lawn gnomes must be considered man’s friendly acquaintance.

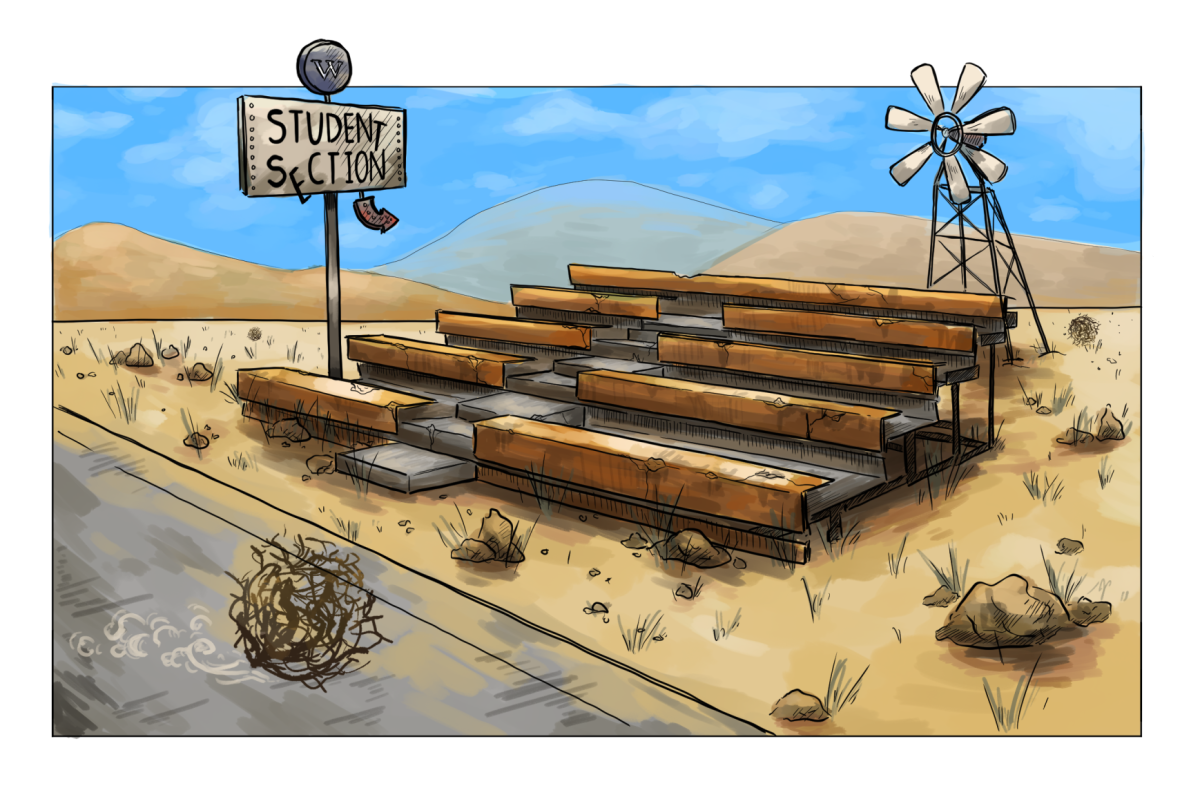

Sadly, this golden period for gnome-rearing didn’t last. The invention of homeowners’ associations and strong lawn pesticides has halved the gnome population. Those that survived have been relegated to the back of the yard … forgotten by all. A few more enterprising gnomes have sought work in the North Pole. Nobody told them that Santa wasn’t real, so presumably, they’re still wandering in the cold and calling themselves elves.

A few Whitman students have attempted gnome revivals, such as running around campus dressed as lawn gnomes to raise awareness, but it’s not enough. A bolder approach is needed. There are millions of fields and grass patches on Whitman campus that could foster a family of gnomes. It’s only a matter of acquiring them. Dean Juli Dunn has yet to comment, so take her silence as permission to put lawn gnomes on Ankeny.