It’s in your face, it’s powerful and, most importantly, it comes in affordable, portable containers — with so many colors it makes ROYGBIV look like a Charlie Chaplin film. Since my freshman year, chalk — the colorful scraping rock — has become a significant form of expression on Whitman’s campus.

My first experience was seeing “ramp” written all over campus, particularly in inaccessible spaces, as a call for better accessibility options — the powerful simplicity of the moniker informing people of a serious issue on campus without much fanfare.

Students for Justice in Palestine (SJP) has utilized chalk as a means of mass communication, organizing events in front of Memorial Building and around Ankeny Field to coat the campus sidewalk in a vibrant collage of the student body’s outrage.

These chalk movements — in no small way — represent the voice of the student body. Chalk is a powerful way to let everyone going to class (which seems to be an unfortunately low number of us) know about serious issues on campus.

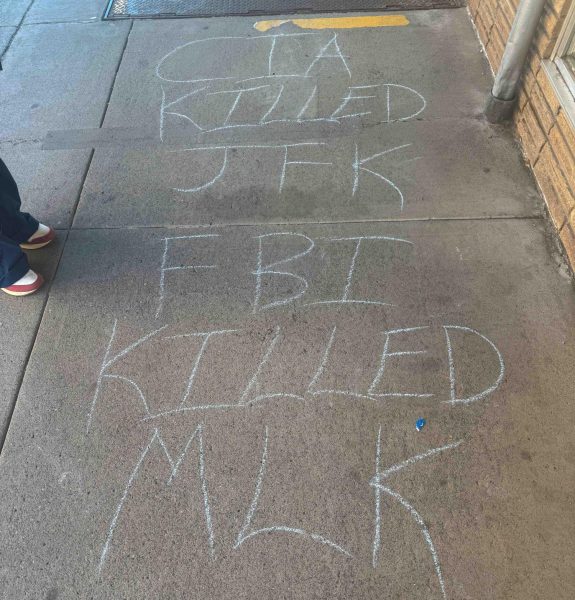

However, one chalk purveyor has become a staple in the news cycle and has been the center of discourse in the broader Walla Walla and Whitman canvas: a man adorned with the almost cryptid-esque moniker of “Chalk Guy.” Throughout the last two or three years, “Chalk Guy” has been driving around Walla Walla and writing various messages in sidewalk chalk – from conservative messaging such as “trans kids don’t exist” to more conspiratorial messages calling into question the existence of COVID-19 or claims that the vaccines include more insidious side effects than the FDA lets on. While he has mostly stuck to downtown Walla Walla, on multiple occasions, he has brought his chalking to Whitman campus. Many worry that his inflammatory chalking will muddy the idyllic image that downtown Walla Walla tries to maintain. Despite outcry from both Walla Walla residents as well as Whitman students, the city has been hesitant to take action against him or similar actors.

In a 2024 message, the City of Walla Walla announced that it would not seek legal enforcement against “chalk guy.” City Manager Elizabeth Chamberlain stated, “While the city does not endorse or support this type of speech — evidenced by staff washing the sidewalks — local government is bound by case law and the First Amendment,” conceding, “While we would love to do something about the sidewalk chalking, we really can’t.”

In response to the city’s inaction, many have decided to “fight fire with fire.” There have been initiatives— especially on our campus — advocating for people to carry chalk with them in order to vandalize his messages, transform them into works of art, or change the wording to convey opposing messages to what he initially wrote. People on both sides seemingly have entered a city-wide game of Splatoon.

Recently, however, a significant development occurred in the saga of Chalk Guy. The City of Walla Walla approved Ordinance 2025-01, which requires anyone chalking in downtown Walla Walla to clean up what they write by 12 a.m. the following day. Failure to do so could result in fines of up to $500. Notably this ordinance doesn’t make any distinction in regard to the content of the markings, stating that “any person who writes, draws, marks, or inscribes words, figures, images, or symbols on a downtown sidewalk.” This means the ordinance would apply equally to hopscotch and conspiracy theories — which frankly makes no sense to me. One is clearly more of a problem than the other… I mean, I’ve seen hopscotch break the ankles of countless innocents.

What’s interesting is that this ordinance seems to be a change from the 2024 statement. If the city previously thought enforcing anti-chalking measures was legally tenuous, it raises questions about how this new ordinance navigates First Amendment protections — which leads to an even more interesting realization, that there are court cases about sidewalk chalk?

The use of chalking as political protest and its status as protected speech have been discussed in several cases over the past two decades. To this day, chalking remains a legal gray area concerning First Amendment protections. District courts across the U.S. have reached different conclusions on this matter. For instance, in Mahoney v. Doe on Nov. 24, 2008, Reverend Patrick Mahoney sought permission from the Metropolitan Police Department (MPD) and the Department of the Interior to write political messages in chalk outside the White House to express his discontent with the recent Roe v. Wade decision. The MPD responded by informing him that his intended chalking would be considered defacement of property. When his request was denied, Mahoney sued the MPD and the District of Columbia for violating his First Amendment rights. The case eventually reached the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals. At the time, Appellate Judge Brett Kavanaugh wrote, “The District of Columbia may prohibit defacement of Pennsylvania Avenue in front of the White House. The prohibition is a reasonable time, place, and manner restriction for purposes of First Amendment doctrine.” In short, this decision found that chalk was not protected by the First Amendment because it qualified under D.C. statute as “defacement.”

A similar case, U.S. v. Murtari (2008), found that chalking qualified as defacement of property. In this instance, the defendant Murtari had a permit to engage in protest in the James M. Hanley Federal Building; however, the permit prohibited “defacing & vandalism.” On two separate occasions, he wrote political messages in chalk inside the Federal Building. He was charged for these actions, and during his defense, he requested the dismissal of the charges, arguing that they violated his First Amendment rights. The court dismissed this complaint, deeming that his actions were not protected under the First Amendment. Again the court found the use of chalk was defacement.

If case law exists that clearly prohibits the use of chalk in the same manner as it has been used in downtown Walla Walla, then why was the city hesitant to put a stop to it? Well, it seems chalk has befuddled the ironclad deliberating capacity of our great justice system, with a multitude of cases concluding the opposite of the above two. One example that Elizabeth Chamberlain brought up when she argued it would violate First Amendment rights to prohibit chalking is Bledsoe v. Ferry County.

On Feb. 26, 2016, a resident of Ferry County, Ms. Bledsoe, wrote the words “sheep” and “jackass” on the exterior of the Ferry County Commissioners’ building. She was subsequently arrested for violating Washington’s malicious mischief statute, which prohibits marking buildings (public or private) with writings, drawings or paintings. Ms. Bledsoe believed that her First Amendment rights had been violated, so she filed a lawsuit against the county commissioners’ office. Then in Oct. 2020, the Eastern District Court of Washington ruled that Ms. Bledsoe’s rights under Section 1983 (civil action for deprivation of rights) had indeed been violated, stating “the evidence supports that the individual Defendants censored Ms. Bledsoe’s speech in violation of the First Amendment based upon her identity and the views she previously expressed” as well as specifying in regards to the use of chalk that, “the Court finds that case law has clearly established that the First Amendment affords protection to symbolic or expressive conduct as well as to actual speech.”

However, we may soon see a more conclusive answer to the constitutionality surrounding chalking with the ongoing case Tucson v. City of Seattle. In 2021, Derek Tucson wrote political messages — some critical of the Seattle Police Department (SPD) — in sidewalk chalk and charcoal on “eco-block” walls temporarily erected by the city outside the SPD’s East Precinct. He wrote the words “peaceful protest” and was arrested under a Seattle ordinance regarding property destruction. Tucson and three other plaintiffs who were detained in similar circumstances sued the City of Seattle, claiming their First Amendment rights were violated. While the case is still ongoing, there have been notable developments so far. The court initially granted a preliminary injunction to halt the enforcement of the Seattle defacement ordinance until the trial concluded, which was later overturned on appeal — the initial granting means the court found that the Plaintiff has standing (can prove harm was done) as well as that the defendants are likely to succeed in finding the ordinance unconstitutional.

Walla Walla is trying to circumvent cases like Tucson & Bledsoe by not making the act of writing in chalk actionable, but only leaving it without cleaning it up — and honestly, it’s pretty clever. If I knew I had to wash down every hopscotch board I set up with soap and water each night, I’d probably cut down on my scotchin’.

While this is not an experienced legal analysis, what’s clear is that chalk possesses unique properties that make it hard to classify — it’s semi-permanent. The fact it gets erased due to exposure after a certain period of time puts it into much more of a gray area than something like spray paint. However, as the city of Walla Walla argues in Ordinance 2025-01, “Chalk markings can remain for more than two weeks in dry weather if they are not cleaned and actively removed.” So chalk at once is harmless in the damage it does to property, but also persists for quite a long time if not washed off.

This leads me to the conclusion that… I just wrote an entire article about chalk, huh?