“This… is the Walla Walla Valley’s only mall”

The statement comes from the long-defunct blog “Walla Walla Valley Daily Photo”. The accompanying photo is a bleak one: a vast blue sky was starkly interrupted by a harsh gray wall and a sign attempting to advertise businesses that had long since shut their doors. This is all according to Becky, the blog’s mononymous author, who documented her daily life in Walla Walla from 2008 until her move to the western part of the state in 2012. In her post, she went on to lament the loss of the mall’s central draws, like Gottschalks and a food court that “consisted of a pretzel and lemonade place and a Chinese food shop that may or may not have been laundering money”.

Unfortunately, attempts to follow Becky’s (impressively vast) web of blogs to find a way to contact her about the post were fruitless, leaving me with only a parasocial relationship to the prolific writer. However, comments on her post about the Blue Mountain Mall, a space now occupied by the Walla Walla Town Center, led me down a rabbit hole not only about the ongoing ups and downs of the shopping center, but the conflicting perspectives on the future of American shopping malls as a whole.

A quick Google search of the question, “are malls dying?”, yields hundreds of articles from the past handful of years, all with seemingly contradictory answers:

“US Malls are Dying”, says Business Insider.

“The US mall is not dying”, proclaims CNN.

“Malls are dying”, according to The Washington Post.

“Malls Aren’t Actually Dying”, says The Atlantic.

The real answer can’t be compressed into a headline, however. Much like with many questions about where things are headed in the future, it takes a nuanced approach to understand all that goes behind it.

In data surrounding mall closures compiled by Capital One Research in May of 2024, it was projected that only 150 of America’s now 1,150 shopping malls may remain by 2032. The current figure of functioning malls in the US is down from 25,000 in 1986. The reasons for this decline are complex and multi-faceted.

The first reason that comes to mind for many people is the prevalence of online shopping. In 2023, the global e-commerce market totaled $5.3 trillion. Experts expect this figure to continue to increase in the coming years, and the proportion of retail purchases made online is projected to grow from 20.1 percent in 2024 by nearly a quarter, 22.6 percent, in 2027.

Nearly every item that can be purchased in person can now also be purchased online, with companies working to eliminate the need for consumers to get out of their chairs to make these purchases. People can now try on eyeglasses on their phones, with filters projecting frames onto their faces in real time, and can envision how a new couch would look in their living room without even having to use a measuring tape.

Online retailers are attempting to mimic the benefits of the in-store experience while continuing to offer the convenience of online shopping. Think about walking into a store and being greeted by a sales associate, who asks, “how can I help you out today?”, followed by an overview of new products and current promotions. Retailers who operate online use pop-ups instead of eager retail employees and give recommendations based on data– what shoppers are clicking on and adding to their carts– instead of being based on conversations with real people in a store. These are all essentially attempts to personalize an inherently impersonal experience.

Another way that the online market is trying to mirror the physical one is through pushing impulse buys. Surprisingly, impulsive purchases are still not as common online as they are in person. 83.5 percent of in-store shoppers report buying more items than intended, while only 72 percent report the same behavior online. Even still, online shopping has expanded greatly and will continue to do so.

This has been one factor in the demise and mass closures of department stores– think Sears, Macy’s and JC Penney– that so often served as anchors of traditional shopping centers. Professor of Sociology and Co-Director of Human Centered Design, Michelle Janning, cites Walla Walla as an example of how these big box stores shutting down can hinder retail expansion.

“In Walla Walla, when a small restaurant goes out of business, it takes less time to be occupied by a new business than a former department store space that is too big to fill without major construction to carve up the space into smaller units,” Janning wrote in an email.

The phenomenon can be easily seen in the original bankruptcy and subsequent 2012 sale of the Blue Mountain Mall. At the time of Becky’s formerly mentioned blog post, the center was already considered a dead mall, with multiple anchors and nearly all of its inline tenants having closed their doors. More recently, it took three years for the lot where K-Mart used to sit on E Issacs to be taken up by the Mill Creek Apartments, which required a full demolition and entirely new construction to take place from the ground up.

A CNBC article published earlier this year discusses “Class A” malls, or higher-end malls that tend to have lower vacancy rates and, importantly, bring in revenues of $500 or more per square foot. As larger chains close and retailers evolve, these Class A malls can afford to shift to what experts call an “experiential” model. Notable features of these up-and-coming experiential malls are attempting to push past the retail-and-food-based structures that prevailed during our parents’ childhoods.

Many of these immersive experiences cater towards kids and families: Lego describes their Lego Discovery Center, with over a dozen locations in malls across the US, as “The Ultimate Indoor LEGO Playground”, all, of course, with retail spaces attached. Spaces like these provide entertainment for kids but assume that parents are present (with a credit card in hand). This goes hand-in-hand with Professor Janning’s observations about the change in how families operate in public spaces over the past few decades.

“[There is a] greater tendency, at least in middle class families, for parents to accompany their children in public spaces, thus removing the previous image of malls as spaces free from adult supervision for teens,” wrote Janning.

At the same time, companies such as Netflix aim to draw in a more adult demographic, with both pop-up and permanent immersive entertainment experiences both based on currently trendy movies and TV shows, as well as nostalgic ones. Netflix can use these attractions to profit not only off of ticket sales, but also the merch they sell alongside the experiences.

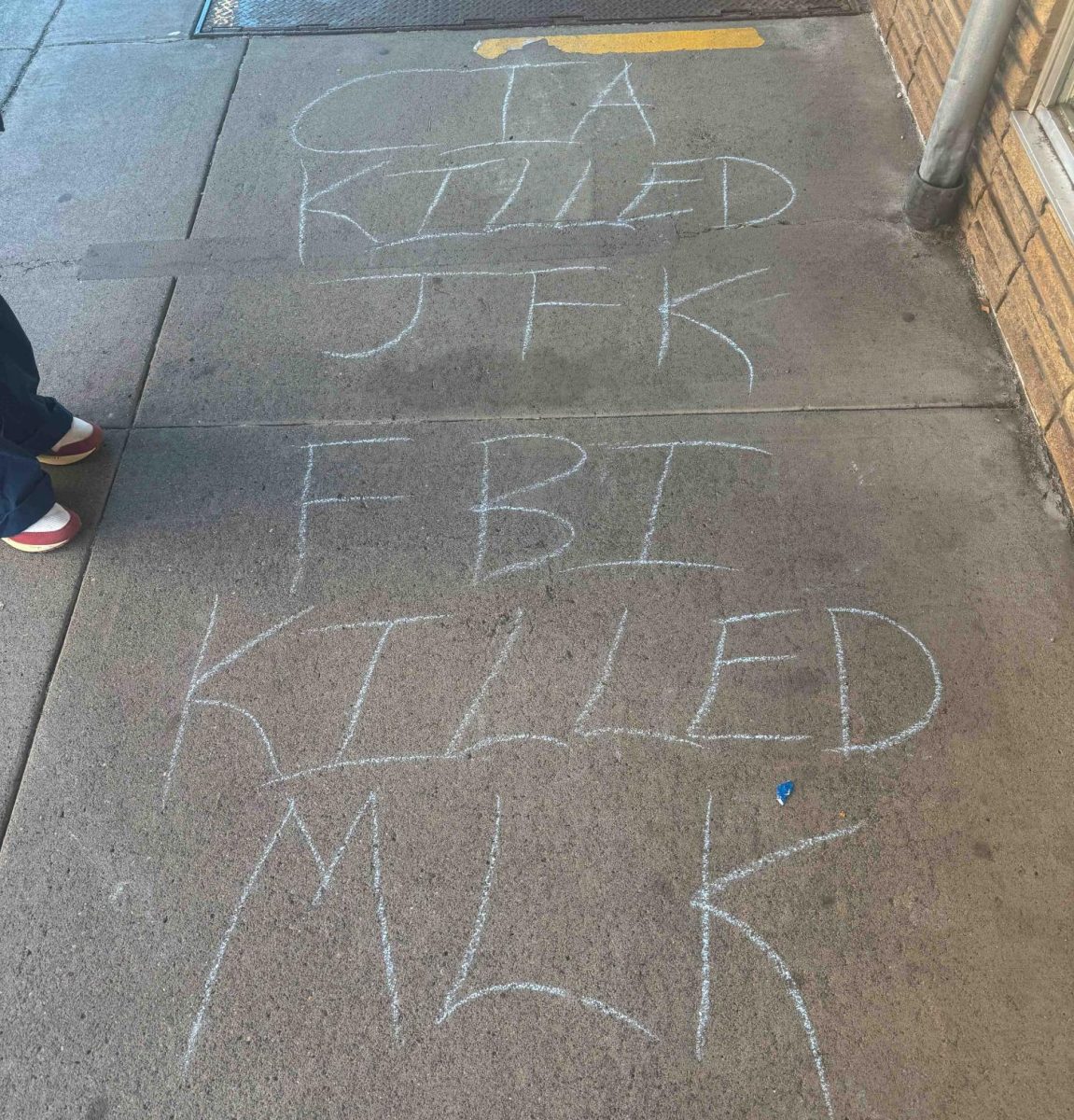

Immersive experiences can also cater towards those who find themselves wanting to break away from the rampant consumerism of the 21st century.

“[We’ve seen] increasing attention toward anti-materialism and anti-fast fashion among people who may have otherwise spent time in these spaces”, Janning wrote in an email.

Even for those who are still avid shoppers, it is important to give consumers an incentive to close their computers and shopping apps and fight through traffic and busy parking lots in order to participate in an activity that can’t be recreated virtually. Wisnu Sugiarto, Whitman’s Assistant Professor of Economics who specializes in urban economics, also cited this as a reason for malls finding themselves needing to adapt. In a conversation with him earlier this week, Professor Sugiarto emphasized how consumer preferences are changing to value unique experiences like these over material purchases, making it important for businesses to keep up with those changes.

Professor Sugiarto also discussed bringing other lifestyle amenities into malls, such as apartments and gyms. He cited a mall near where he grew up in Indonesia that housed a university. It created a win-win situation: students had everything they needed within a small area, bringing business and foot traffic to the mall and the university didn’t have to invest into dining areas or other amenities that were already built-in. American malls are catching onto this model, building apartments that appeal to young adults’ desire for community and convenience, schools in place of vacant retail spaces and even doctors’ offices and medical centers to round out the live-work-play atmosphere.

Stepping into an urban economics viewpoint, Professor Sugiarto mentioned the positive economic impacts that busy malls can have on local economies.

“Malls can also be an amenity, a reason for people to move to an area,” Sugiarto said.

Of course, these benefits are only accomplished when malls are successful. Finding this success is only growing more complicated, as our modern, digital age continues to change the way we make purchases, what we value and the way we socialize.

American shopping malls are at a pivotal crossroads, finding themselves needing to sink or swim. Those who can afford to stay afloat are doing so by pushing beyond the nostalgic indoor malls of the late 20th century and pushing uniquely offline experiences. However, many malls that can’t provide reasons for consumers to leave the comfort of their homes are sinking. They are going down the same path as the Blue Mountain Mall. Smaller and less popular malls around the country are losing anchors and inline tenants, unable to entice businesses to move in and provide an economic boost for the area. Like many things nowadays, the contrast and divide between these two situations is growing more vast.

So, all those articles declaring the death and downfall of the American mall are true to some extent, but so are the ones who claim that malls are thriving now more than ever. The old, traditional model of the shopping mall is going steadily downhill, but a new evolution of malls is finding its footing. We can only be left to wonder how Becky and her commenters feel about the shift, and what they hope for the future of the Walla Walla Town Center.