It’s no secret that frustrations with the United States economy are widespread among many Americans. Complaints about inflation, the cost of living and the wealth gap have run rampant to the point that they have become banal refrains. However, they aren’t unwarranted: It’s easy to feel powerless as individuals living in an economy whose strings are pulled by multibillion-dollar corporations and the top one percent.

It’s especially easy, too, when companies aren’t transparent with their customers. From Wendy’s to Walmart to Ticketmaster, reports of businesses engaging in economically dishonest practices have abounded in recent years, having most recently manifested as dynamic pricing. Compounding this atmosphere of economic corruption is a high rate of economic illiteracy. The average American does not have a firm enough grasp on economic concepts like dynamic pricing to be able to combat forms of economic malpractice in their everyday lives. Given these circumstances, an understanding of how companies set their prices, the mechanisms by which prices shift and the impacts of price shifts on consumers is crucial to sustainable participation in the U.S.’s increasingly digitized, capitalist market economy.

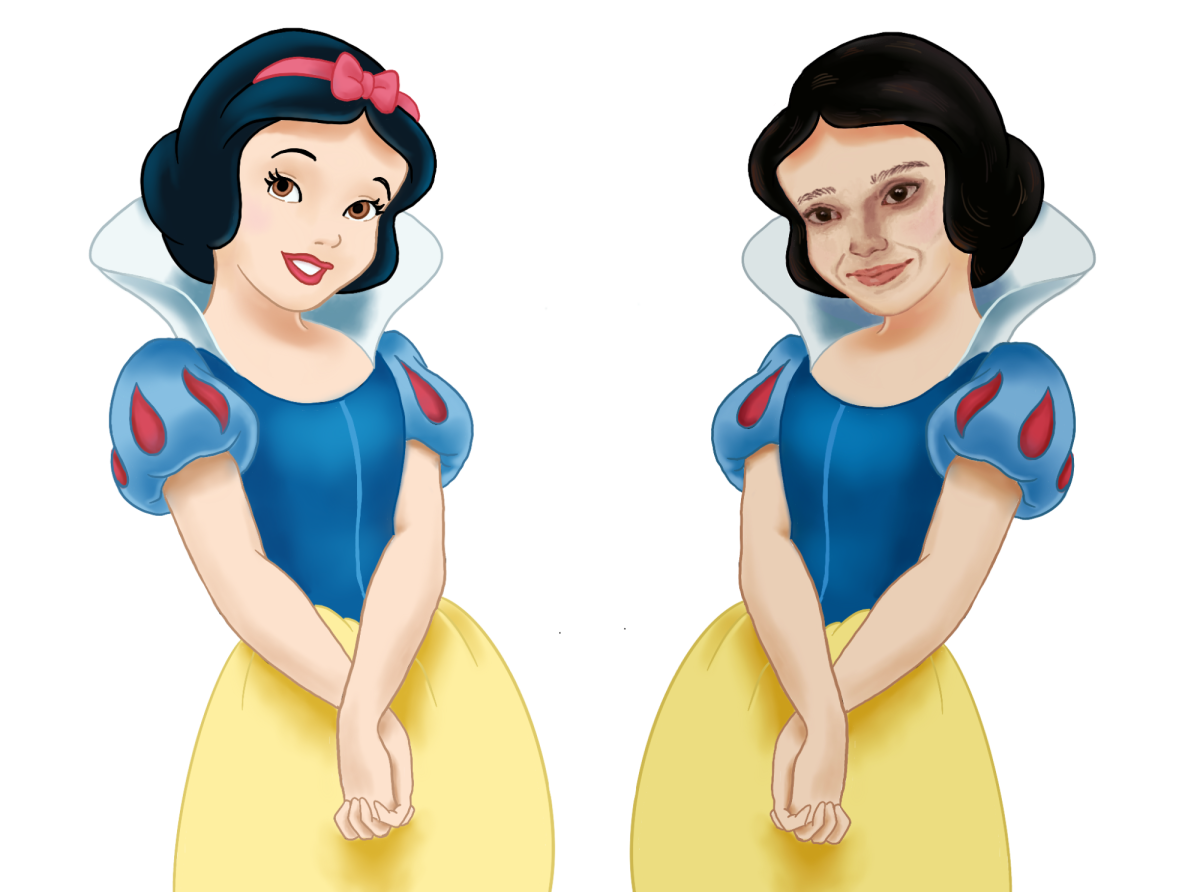

Businesses often set their prices through dynamic pricing, the process by which product prices are adjusted according to market conditions of supply and demand. Dynamic pricing, also known as surge or variable pricing, appears in various areas of our lives as consumers, often in recognizable ways. For example, ride-share services and gas stations tend to raise their prices during periods of high demand. These practices are legal, so long as they are not influenced by specific demographic criteria like race and gender. That sort of cost manipulation is known as price discrimination and is illegal as dictated by the Robinson-Patman Act of 1936. Another form of cost manipulation sometimes conflated with dynamic pricing is price gouging, which corporations often turn to in the wake of natural disasters and public health crises to escalate prices as demand spikes.

However, the legality of dynamic pricing doesn’t necessarily mean that consumers like it. Complaints related to dynamic pricing often stem from individual price fluctuation, which constitutes differential economic treatment. Cost changes that impact groups, though, are less likely to receive pushback from consumers.

Wisnu Sugiarto, Assistant Professor of Economics at Whitman, mentioned these complaints in his discussion of dynamic pricing. He cautioned against allowing them to feed the misconception that dynamic pricing automatically raises the costs of products and is therefore the right-hand man of money-hungry corporations.

“From consumers’ point of view, we typically do not have a lot of benefits when we buy something expensive, but dynamic pricing gives the ability for producers or sellers to essentially adjust their prices more quickly, especially in real-time,” Sugiarto said.

Though it might seem unfair at face value, Sugiarto explained that dynamic pricing is designed to alter prices in logical ways based on a variety of market factors. In other words, companies do not (or not legally, at least) change their prices arbitrability; rather, price changes are the result of careful consideration of market conditions.

Companies like Walmart are beginning to lean into the potential of dynamic pricing, swapping out physical price stickers for what are known as electronic shelf labels. These labels make it possible for employees to alter prices at any time, which retailers say would increase efficiency in stores, allow customers to access additional information about products by scanning shelf label barcodes with their phones and help offset the rising costs of labor that come with higher wages for employees.

Sugiarto emphasized the fact that dynamic pricing does not necessarily result from such a switch.

“… [This switch is often] for efficiency of cost, like saving paper or just saving the time that [it takes] people … to update price tags,” Sugiarto said.

Sugiarto also explained the importance of considering the distinction between seller and producer when thinking about dynamic pricing.

“… [Dynamic pricing] might give companies more power, but I think it’s also important to think about … [the fact that] the prices at the store might be dictated by the grocery stores … not necessarily from the producers [of the products],” Sugiarto said.

Nonetheless, there is always a possibility that companies might use these shelf labels to raise prices in non-consumer-friendly ways. The reality, though, is that most companies are making this switch to better manage their pricing approaches by taking factors like competitor prices and supply-and-demand into account. By doing so, they are hopeful that they will be able to better solve the economic conundrum that faces every business: how to maximize profits while ensuring that costs remain competitive.

Keeping pace with competition is especially important in an economy increasingly defined by e-commerce. Dynamic pricing allows companies to do so by taking advantage of real-time market trends to create prices that reflect the state of the market.

On the other side of the coin, though, dynamic pricing can sow consumer distrust and, if faulty data sources are used to implement it, reduce profitability.

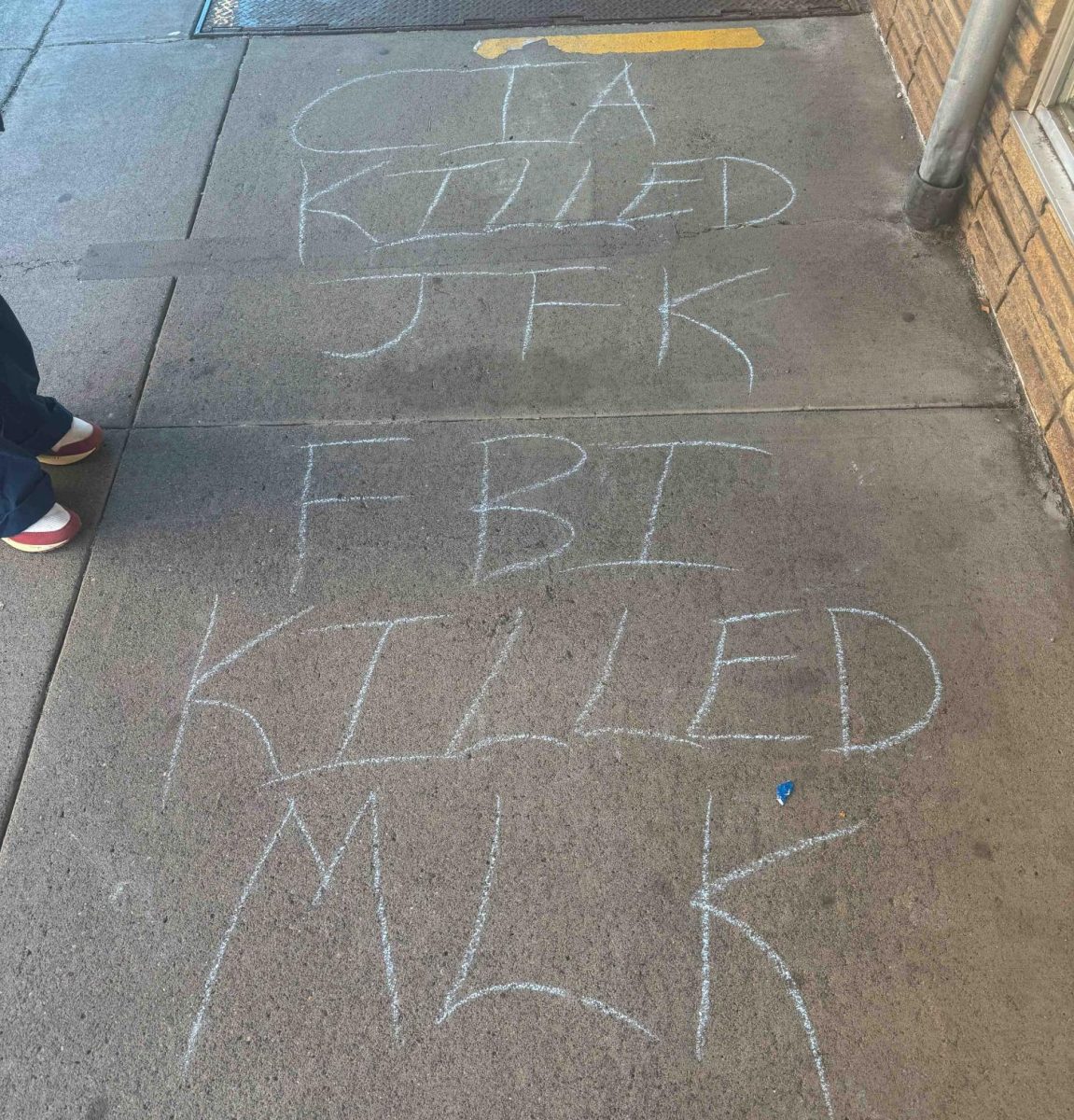

A prime example of this is the recent controversy over Ticketmaster’s concert ticket sales, which rose to exorbitant amounts because of unchecked dynamic pricing by the company. Debacles like this one make it easy to see how dynamic pricing, when left unmonitored or exploited, can have a significant deterrent effect on consumer activity, hurting both businesses and their customers alike. Not only that, but companies can easily market their policies as dynamic pricing to cover up economic deception, which can exacerbate customer confusion and distrust.

Dynamic pricing also doesn’t do much to reduce the power imbalance that exists between small businesses and corporate behemoths.

Sugiarto talked about the challenges that small businesses face with dynamic pricing.

“If you’re a small business, you cannot always adjust your cost[s] as eas[il]y as bigger companies,” Sugiarto said. He also pointed out that, by definition, small businesses’ market influence pales in comparison to that of larger companies.

This is especially relevant to cities like Walla Walla. While its number of small businesses has significantly decreased since 2022, over 50 percent of businesses in Walla Walla are small ones as of 2023. These local companies must pay close attention to regional market dynamics, as well as a whole host of other factors: seasons (many of Walla Walla’s primary industries, like wine, are driven by seasonal fluctuations in demand), chain corporations like Walmart and Target and intense concentration of industry, to name a few.

Rural-based economies such as Walla Walla’s rely as much on consumers as they do on core industries. Sugiarto offered advice for consumers on how to use dynamic pricing to their advantage when buying products.

“When you have dynamic pricing, it becomes a race [to get to products when supply is still high],” Sugiarto said.

With that in mind, purchasing products when they are in abundant supply is of considerable importance.

In addition, Sugiarto suggested that individuals track the prices of company products online. This can be done by ensuring that one is notified by businesses when their prices change, including when things go on sale.

Strategies for interacting with larger companies are a different ball game altogether. Especially as mainstream retail (think Amazon and eBay) continues to shift toward online forums, consumers would do well to be aware of the role that their personal data may play in the prices that they receive online. Companies often ask for personal information in exchange for benefits or notifications about deals and, depending on the consumer, this tradeoff may or may not be worth it.

These tips are a step in the right direction toward achieving economic self-sufficiency, especially for college students looking to maintain tight budgets and still spend occasionally. As dynamic pricing continues to embroil businesses in controversy and integrate itself into new industries, discourse around corporate-consumer relationships and pricing ethics is sure to be influenced.