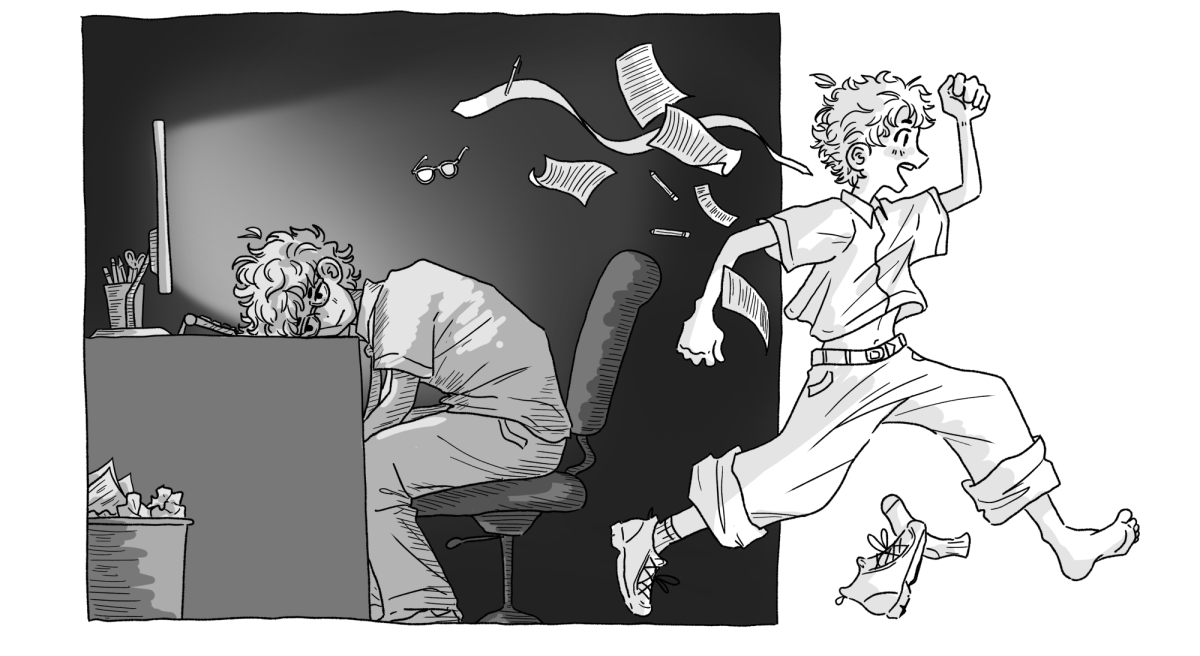

The Social Model of Disability animation envisions a town that is populated solely by people who use wheelchairs. The town is physically designed for such people and has no high ceilings or doors as a result.

Eventually, the town receives able-bodied visitors. They quickly notice that things are off in wheelchair land; namely, they can’t walk through doorways without hitting their heads and injuring themselves. It becomes apparent to them that the town is not built with them in mind.

This becomes apparent to the town’s wheelchair users, too, and they begin to collaborate to fix it. Hard hat helmets are made and distributed to able-bodied people for free. Especially inclined wheelchair users form committees and raise money to solve the “problem of the able-bodied.” Through these processes, the visitors are gradually integrated into a society that was once inhospitable to them.

Though fantastical and far-off-sounding, this model demonstrates that there is no fundamentally objective basis for how society is physically or culturally configured.

Make no mistake: discrepancies in ability do exist in apparent ways. Reconsidering this model can help one determine whether these discrepancies are inherently meaningful or whether society defines them, thereby assigning them significance.

For many who are diagnosed with a disability at birth, the ‘disabled’ label is all they know for the rest of their lives. As someone born completely deaf, I can attest to the stickiness of the term.

Others’ diagnoses foster in them different self-conceptions of their disabilities. Sophomore Grace Hardy, for example, was diagnosed with an invisible disability when she was about thirteen or fourteen. Her diagnosis occurred in the process of testing for her father, who is in the military.

“They categorize your family by what medical treatments your family needs, and then they send you to military bases [partially] based off of that,” Hardy said.

Hardy talked about the experience of her diagnosis, when her doctors might have gotten an inkling that something unique was taking place, but she didn’t catch on.

“It was never, ‘You’re disabled.’ It was, ‘You have this [condition].’ I was young, so I wasn’t like, ‘Oh, this is bad,’ …as far as I knew, that’s how everyone was experiencing life,” Hardy said.

Sara Marshall, a senior with type 1 diabetes, shared a similar diagnosis experience.

“I was so young. [At] six years old… you don’t have enough life experience to understand what’s being told to you. It’s just people in white coats telling you that some fundamental aspect of your life is going to change,” Marshall said.

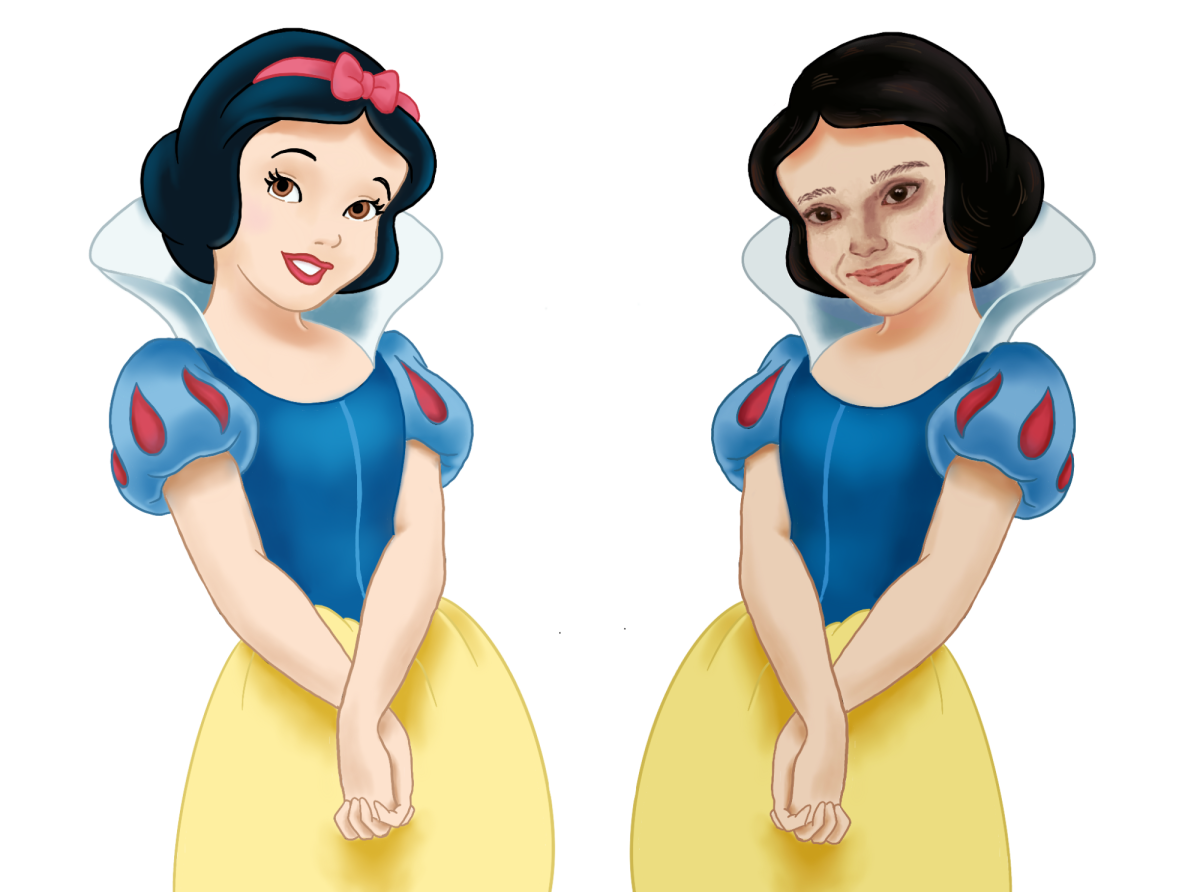

Both Hardy and Marshall’s perceptions of their conditions were profoundly influenced by the highly restrictive societal model of a ‘typical’ disabled person.

“[I was taught that] this is what disabled looks like, and this is what it doesn’t look like. I don’t have a chair, I don’t have a crutch, I look able-bodied. […] Because I don’t have these things, I’m not in that category [of ‘disabled’],” Hardy said.

“Diabetes has taken the form of a somewhat invisible disability, which… has left me questioning where my place is in the disabled community… legally, according to the ADA [Americans with Disabilities Act], I’m disabled. […] Socially, I’m not seen as disabled,” Marshall said.

Fuzzy notions of what disability is and isn’t have manifested themselves in Hardy’s accommodations experience.

“I feel like admin is always thinking [about students who request accommodations], ‘Well, are they lying? Do they really need this, or do they just want it easier?’” Hardy said.

At Whitman, accommodations are provided by the Academic Resource Center (ARC), which equips students with a variety of educational supports such as disability services, tutoring and academic coaching.

Kassandra Vinton, the Disability Support Services Specialist at the ARC, offered an overview of the accommodations process at Whitman. In an online application, students answer basic questions about their disabilities and the impacts they have and provide documentation of their disabilities. Next, students meet with Vinton and Sheri Noble, the ARC’s Disability Support Services Consultant, to discuss the implementation of their accommodations. Once accommodations are approved and the necessary paperwork is completed, letters of accommodation are sent to students’ faculty members.

Vinton acknowledged the challenges that the accommodations process can pose for students.

“Asking a complete stranger to tell you the hardest things about your life is scary and it’s anxiety-producing… so we do try to make it [the process] as streamlined and as friendly as possible,” Vinton said.

For Marshall, however, the accommodations process at Whitman leaves much to be desired regardless of its time-consuming and tedious nature.

“A lot of the culpability is, of course, put on you as the individual. […] I have certain qualms about accommodation systems because they’re just a band-aid. They can only mitigate,” Marshall said.

Hardy mentioned the volume of accommodation-related complaints that she receives from other students as an indication of Whitman’s imperfect accommodations process.

“I get emails once a week from members of DISCO [the Disability and Difference Community] [and] people who aren’t members of DISCO [with questions related to accommodations],” Hardy said.

ARC staff recognize that there is room for improvement. Director of Academic Support Services at the ARC, Richard Middleton-Kaplan, encourages students to communicate their feedback.

“We want to hear about what students’ experiences are… with seeking and receiving accommodations,” Middleton-Kaplan said.

Accommodations are one thing, but campus accessibility is another. Hardy cited the Glover Alston Intercultural Center (GAIC) as an example of the lack thereof on campus. Known as the hub of affinity clubs, the GAIC has recently been under construction. The construction has not rendered it unusable, however—at least, for those without mobility disabilities.

“With construction going on right now, it’s [the GAIC] inaccessible. The ramp that they have there has planks over it. So, if you were to use a mobility aid, you could not go over the ramp to get into the one building that’s supposed to be for you,” Hardy said.

There are many other examples of building inaccessibility at Whitman.

“In Cordiner Hall, if you are using a wheelchair, you are segregated to the back to watch anything. If you need an accessible event, it has to be in Reid Ballroom,” Hardy said.

Hardy expressed her frustration with the justifications offered by the Whitman administration for inaccessibility.

“It’s always ‘Institutional speed. These things take time. We can’t do everything overnight.’ I feel like that’s understandable to a certain extent, but also, come on…You can get a different ramp. A wooden plank would be better than what we have right now,” Hardy said.

Similarly to the physical campus, Whitman’s social environment is less than fully welcoming to disabled students.

“A lot of Whitman students are very friendly… [and] are willing to suspend their judgment to learn about things they don’t understand. But collectively as a group, it does not feel safe. […] If you think about the image of the Whitman student, it’s this able-bodied… person… When there are deviations in that, it falls under the umbrella of Whitman [as a] welcoming, inclusive, diverse space, but the inclusion of those people [that deviate from the norm] with this malignant stereotype makes them feel excluded or puts pressure on them to conform,” Marshall said.

“People are aware that [some] people hold these identities, but it’s not enough… there has to be some level of understanding,” Marshall said.

There’s no sugarcoating it: living with a disability can be a deeply oppressive and isolating experience at Whitman and in other settings. Still, disability by no means precludes happiness and self-fulfillment. On the contrary, many people find—or learn to find—pride and joy in their disabilities.

For Marshall, responsibility, though at times a burden, has instilled itself in her as a life skill because of her disability.

“Being in charge of your own mortality, in a sense…, definitely cultivated in me a large sense of responsibility and maturity. Talking with all of these adults, having to explain complex things to many people, those are hard skills that I was forced to learn but did come to benefit me later in life,” Marshall said.

Marshall’s diabetes has also made her a more accepting person.

“It has tempered my judgment in the sense that you can’t experience so many microaggressions and slights against your humanity without also finding a sense of compassion and empathy in yourself for other individuals who are probably experiencing similar, if not the same, things as you are,” Marshall said.

Thanks to her disabilities, Hardy has learned to prioritize equitable access for all.

“Every single thought I have is filtered through accessibility… I’m going to this place; I’m planning this event—is it accessible?” Hardy said.

It remains to be seen if Whitman and other higher education institutions can adopt or more fully integrate this mindset into their academic and campus cultures.

In the meantime, students’ needs continue to diversify as disability is increasingly destigmatized. Noémie Studer, the Testing and Tutoring Coordinator at the ARC, emphasized the ever-changing nature of disability services work.

“…There is this constant growth of awareness [as part of working with students],” Studer said.

Embracing this change, committing to growth and striving for excellence in all facets of accessibility is key for Whitman to make all its students feel welcome and thereby unleash students’ true potential.