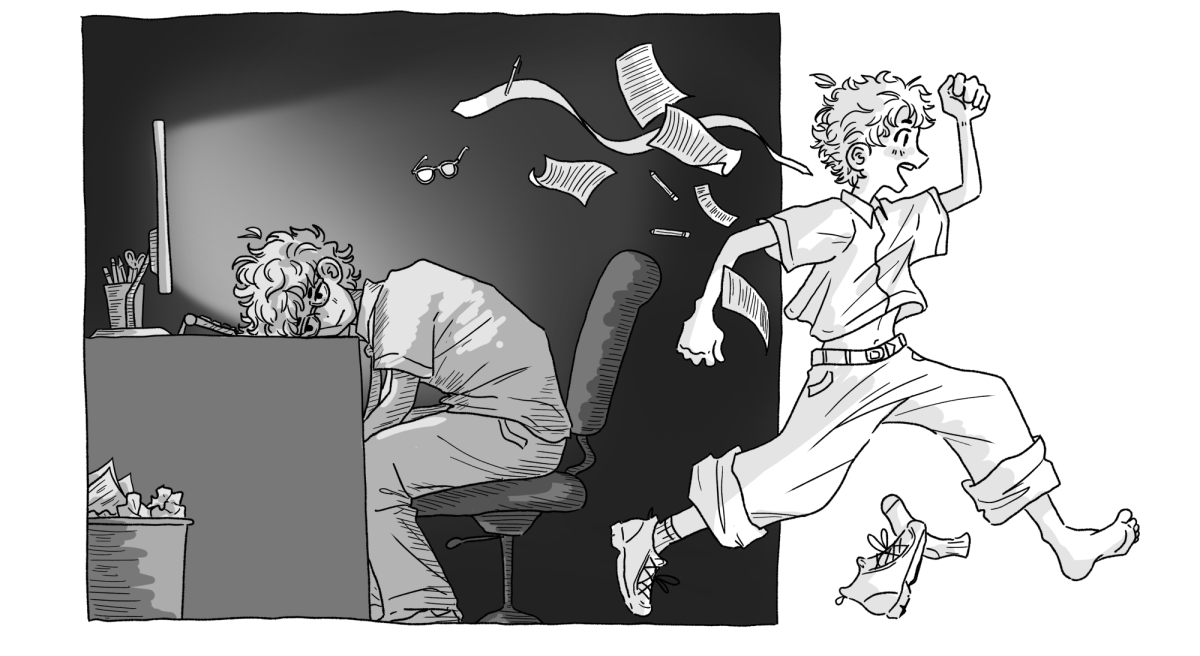

Be it Instagram, Tiktok, or any of the other hundreds of apps and websites designed to hijack our attention spans (or lack thereof), there is no shortage of online avenues to doomscroll our lives away. In fact, over the course of writing this article, I have taken multiple doomscrolling ‘breaks.’ The irony of doing so while writing an article on the very same subject is not lost on me. The gravity of it isn’t, either: That I can be acutely aware of a personal behavior, spend time and effort researching and writing about its dangers and continue to feel compelled to engage in it is unsettling, to say the least. This isn’t an article about me, though, at least not entirely; it’s about all of us, our phones, news and social media, and the summation of the three: the insidious yet irresistible pastime known as doomscrolling.

Doomscrolling is defined as spending excessive time online browsing news or content that triggers feelings of sadness, anxiety, or anger. A 2024 study found that about one in three adults in the United States who are active on social media report doomscrolling regularly; this number rises to one in two among members of Gen-Z. Undoubtedly, doomscrolling—the excessive consumption of negative online content, including news and social media—is ingrained in our daily lives. Whether we like it or not, it is functionally inextricable from existence in the 21st-century information economy.

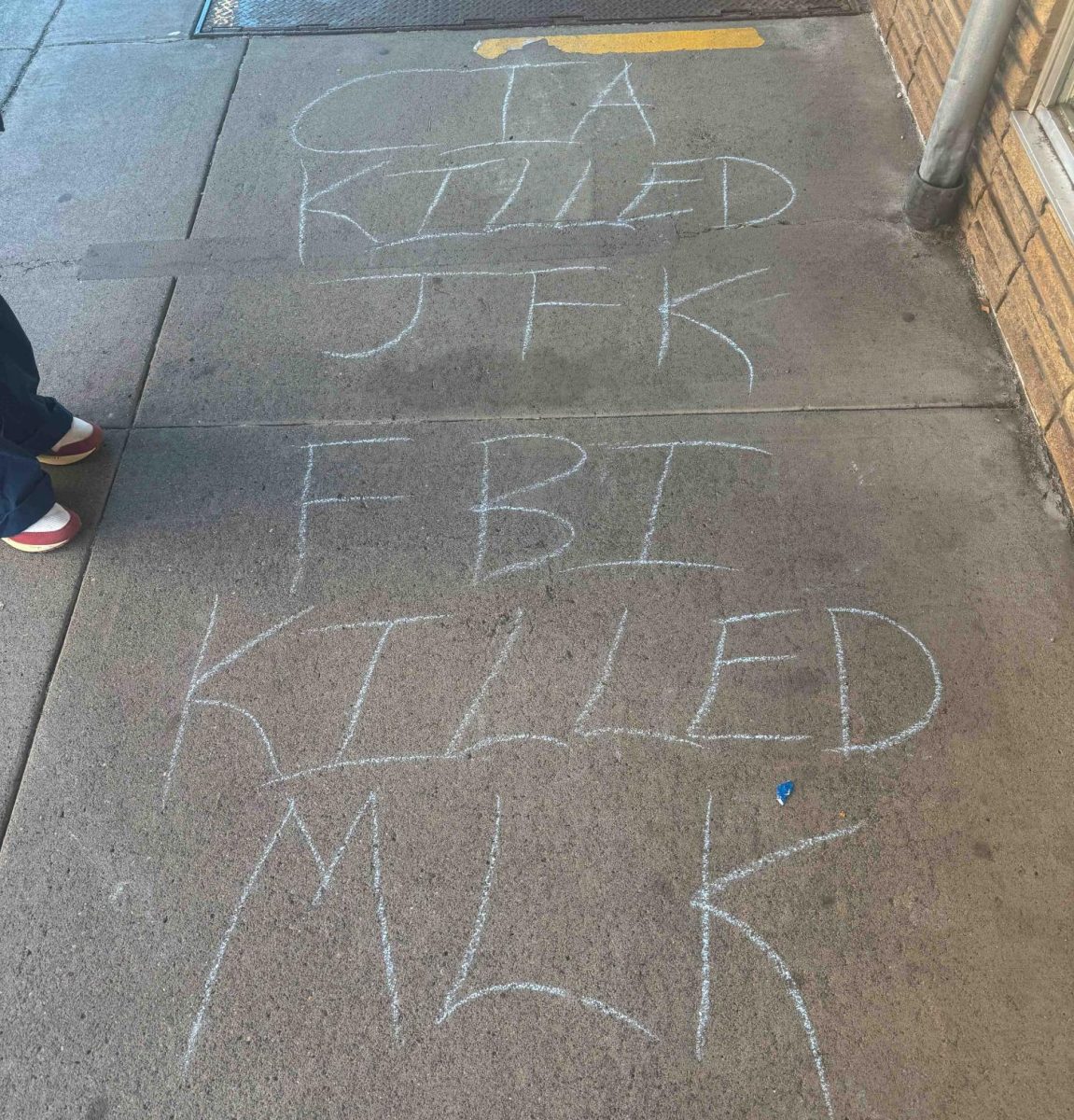

To be sure, doomscrolling is a contemporary phenomenon and a fairly recent one at that. The term has existed in some form since 2018 and broke through onto the colloquial scene during the COVID-19 pandemic when online news consumption spiked. However, Assistant Professor of Psychology, Erika Langley, explains that its behavioral basis predates early human evolution.

“We have [an] overall bias, or a sensitivity towards, negative information,” Langley said. “This bias is rooted in our evolution as a species and the need to deal with serious threats. Furthermore, when we feel uncertain about things, like when there’s a stressor we might not be prepared to deal with, we are innately wired to regain a sense of control.”

Langley talks about how doomscrooling can affect us from an emotional standpoint,

“Doomscrolling can function as a way to manage our anxiety… it creates this sense of preparedness,” Langley said.

Doomscrolling may be our solution to a so-called absence of control—but its success in filling that void is a façade.

When doomscrolling, senior Jack Dorsey feels proud that he is consuming news and therefore views his habit as highly functioning. Dorsey continued to talk about the payoff, though, which he describes as an onset of shame and disgust at having wasted time online.

Junior Emily De La Cruz Hofer, also observed that doomscrolling reduces worry in the moment but ultimately increases feelings of anxiety.

Freshman Cordelia Seiver noticed that engaging with social media at all becomes doomscrolling.

“I feel like I don’t have control anymore,” Seiver said.

Dorsey, Seiver, and De La Cruz Hofer aren’t alone in these sentiments. As Langley explains Doomscrolling might initially feel reassuring, but it can result in obsessive thinking and constant focus on bad news.

“Doomscrolling can validate the negative feelings that we have around [certain] events,” Langley said.

Despite these impacts, doomscrolling continues. Langley also described doomscrolling as functional even though she views it as maladaptive.

Lisa Honold, the founder of The Center for Online Safety, detailed the variety of ways in which this maladaptation can manifest itself.

“Doomscrolling encourages excessive screen time and actually trains the algorithms on social media platforms and search engines to deliver MORE of that negative content,” Honold said.

In addition to screen time concerns, a host of mental health issues are raised by doomscrolling. Langley identified chronic stress, anxiety, overtaxed stress and fight or flight responses, hypervigilance, depression and pessimism as common effects of a prolonged online bout.

“You’re anxious about what’s coming up… Or you’re depressed about what’s already happened,” Langley said. “What’s left behind is the ability to live in the present,” Langley said.

Dorsey explained that, in his opinion, our current way of consuming information is abnormal.

“Humans aren’t meant to consume this amount of information this quickly,” Dorsey said.

In addition, the human brain is not capable of multitasking. These factors explain why doomscrolling is not mutually compatible with any sort of focus, which we lose when we attempt to pair online activity with other responsibilities.

Lesser known but just as impactful are the physical harms of doomscrolling. For example, sleep is affected for the worse. Langley talked about this effect.

“If you’re doomscrolling before bed, you [are] creating this cascade of cortisol [a stress hormone]… in your body, which makes it harder to get to sleep… which can then negatively impact your cognition, emotions and social relationships,” Langley said.

As ubiquitous as doomscrolling is in our daily lives, and as cognizant as many of us are of its damaging effects on our health, the habit itself persists. For anyone, but especially for college students coming into their own amid intense political turmoil, global calamity and an era of mass media and information, it is a habit that must be broken.

If the rapidly decreasing attention spans that we joke about with our friends aren’t reason enough to provoke attempts at modification, doomscrolling poses additional concerns related to academic success in a college environment. Langley comments on the role it plays.

“Doomscrolling… [is] a significant source of distraction for all of us,” Langley said. “Being in a college environment can magnify the importance of peer norms and social validation.”

These pressures are key when considering the burden of maintaining a social media presence that Seiver mentioned when discussing their experience online.

Given these concerns, it is easy to feel overwhelmed by the task of cutting down on doomscrolling, succumbing to the comforts of inaction and reverting to long-since-formed online routines.

Making adjustments doesn’t have to feel like such a monumental task, though. It is possible to “set healthy limits” for safer engagement with news and social media without abandoning technology altogether.

We can set these limits in a variety of ways. For starters, Honold talks about the importance of sourcing where we get our information from.

“Get your news from various trusted sources, not just those with bias leaning left or right, depending on your point of view,” Honold said.

Awareness is also key. Honold encourages us to understand that social media platforms are intentionally built with features that encourage you to spend too much time online. She advised paying attention to your emotions and stepping away from your phone when you find yourself getting caught up in negative spirals. Honold says that noticing physical cues from your body while online—hunched posture, a fast heartbeat and strained eyes, for example—can help foster intentionality as well.

Even small steps make a difference. That’s why actions as simple as keeping your phone in another room or otherwise away from you, especially when studying, can maximize efficiency and focus. Honold also offers more advice for the doomscrolling problem.

“Rather than just consuming bad news but getting paralyzed about all the issues, pick a topic that you care about and take action… Get involved in a meaningful way and you’ll start to feel like you can make a difference. That adds positivity and meaning to your life and inspires others to do the same,” Honold said.

There is something to be said for the fact that doomscrolling, for all its perniciousness, shows that we care. Although we consume news in an unhealthy way by doomscrolling, we are, at the very least, actively choosing to consume it; it follows, then, that we are invested in the well-being of those around us, from our families and friends to strangers across the globe. By striving to act as global citizens in healthy and meaningful ways—by resisting the lure of doomscrolling—we can better ensure that our humanity uplifts instead of discourages.