Riding the wave of climate emotion

September 29, 2022

It’s rare that I go a day without thinking about climate change.

Sometimes, my thoughts circle around facts, statistics and the latest news. But more often, my mind returns to feelings so convoluted that I don’t fully understand them, but I know enough to sense a healthy mix of fury, grief and helplessness.

People experience a wide range of emotions connected to climate change, and it’s impossible to generalize how a person should or shouldn’t feel when the spectrum of emotion is so vast. My experiences and emotions will be different from yours, but that doesn’t make either of them less valid. Mostly, it makes them confusing, especially when our emotions change and warp, leaving us unmoored.

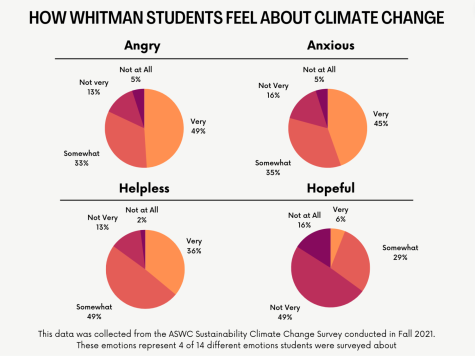

The above infographic provides a small sample of over a dozen emotions the ASWC Sustainability Committee surveyed students on. Even within different emotions, there’s a range of how strongly we feel certain emotions. And sometimes, we don’t even know what we’re truly feeling.

“I think sometimes we act out in anger when really we’re afraid or we’re grieving something, and anger can be a quick response,” Edward F. Arnold Visiting Professor of Environmental Humanities Camille Dungy said.

If that wasn’t complicated enough, these pesky feelings can metamorphose into a lopsided, chaotic and altogether funky, emotional butterfly.

In Professor Dungy’s writing, she notices that “other possibilities come forward: hope, joy, nostalgia, even a kind of peace.”

Coming to terms with the variability of climate emotions can help us be receptive to our own needs and come to a place of stability. In other words, we need to chase after those butterflies of possibility, even if we don’t quite know where they’re heading.

Before we embark on that journey, it’s important to acknowledge that these feelings and risks are exhausting, and we’re already exhausted enough. With an issue as large as climate change, it can feel like there’s nothing we can do. We can grow anxious and hopeless about the future as we watch countries refuse to take action and temperatures increase. Unfortunately, this apathy lends itself to a negative feedback loop: hopelessness over climate change leads to inaction, which only makes despair worse.

This personal inaction can grow when we see larger institutions and structures remaining similarly inert. This is something that senior Fraser Moore notices at Whitman.

“[Whitman has] no current relevant climate action plan. There’s nothing driving a visionary future for the school,” Moore said. While talks for institutionalized climate action were in the works, no real progress has been made and what does exist is outdated. A disconnect exists between the goals of the administration and the students, making cohesive action difficult.

Not only does Whitman repress student voices rather than amplify them, but it also enjoys a privileged position in relation to the rest of the Walla Walla community, as do many of the students. Whitman’s privilege begs the question of what it and the students can be doing to address social and environmental inequities.

“We still have far more security in housing and food than large parts of Walla Walla,” Moore said, noting the difference between the vulnerability of many Whitman students and other local communities. This discrepancy exists thanks to Whitman’s shaded green spaces and air-conditioned buildings, which provide students with a cooler escape than many other residents can access.

Even with Whitman as a resource, Moore spent a summer with temperatures high enough to drive him from his un-air conditioned home between the hours of 10 AM and 10 PM. He kept his windows open at night to cool his room to a bearable temperature, which became an issue when smoke from nearby wildfires settled in the valley and invaded his home. Many students find themselves in similar impossible situations, unable to escape environmental hazards in their off-campus homes.

“Whitman should engage in how students are going to live in a climate that is heating with houses that aren’t designed and aren’t equipped to sustainably run air conditioning,” Moore said.

This is one of the areas in which he believes Whitman can improve. However, this isn’t to say that our attention should be focused on Whitman alone. There are over 30,000 people living in Walla Walla in increasingly vulnerable positions, even if it’s easy to forget that from our place within the manicured Whitman bubble.

That’s a lot of people, and 30,000 is only a tiny fraction of everyone struggling with a warming climate. A problem of this sheer magnitude is humbling, sometimes to the point of shutdown. With such hurdles to overcome, we can find ourselves wondering what options, if any, we have for positive change.

“Silence is alienating and it keeps people stuck,” Lily Seaman, a therapist at the Counseling Center, said.

To break free from the crushing isolation that can come with climate distress, Seaman urges people to talk about the issue and normalize the turbulent emotions they may be feeling. Speaking up, being vulnerable and finding a community are often the first steps in dealing with climate change.

And even more important: “The biggest way of managing psychological distress around climate change is taking action, no matter how big or small, even and especially if you’re feeling hopeless,” Seaman said.

Moore also identifies action and dialogue as key solutions and discussed the ways in which students can get involved both on campus and in the broader community.

One key option for action is the Campus Climate Coalition, or CCC, which students are reviving this semester. COVID-19 wiped out several student groups, including the previous CCC and Sunrise Movement. Luckily, climate organizations are recovering and hope to offer students a space to generate powerful change.

Action can take form outside of organizations as well. Professor Dungy is well-versed in approaching climate change through her writing. Not only can writing and art be cathartic for people confronting complex emotions, it can also inspire societal change.

Stories and art allow us to explore possibilities, inspiring us to strive for a future we want to live in. This power is not new.

“Plato did want to kick the poets out of the Republic, partially because poets are always imagining another possibility,” Dungy said. Literature and the arts can challenge society and offer options for improvement, which is why we turn to stories again and again as we hunt for change and inspiration.

Outside of action, there are other ways students can cope with climate distress. Like the emotional reactions to climate change, these coping mechanisms can vary from person to person, so it may take time to find what works best for you.

For Moore, getting outside and slowing down helps him ground himself and connect to nature. He feels a “maternal comfort in the natural world” and seeks to “really look and pay attention, listen, smell, hear and feel.”

Like for many of us, the COVID-19 pandemic stripped Professor Dungy of commitments and distractions, forcing her to sit with excess time and space. During that seemingly endless time, big questions and ideas emerged. As she immersed herself in her home, family and garden, these ideas helped her “synthesize all those many strands of tumultuous experience.” From that synthesis, her latest writing project emerged.

As she acclimates herself to Whitman, Dungy has found particular relief and joy in spaces like the Water-Wise Garden, where native plants thrive. This is something she would like to see more of and Moore agrees.

Fostering the growth of native plants is not only healthier for the environment, as native plants require less water and have evolved to thrive in this climate, but is also a form of decolonization. This is just one area where students can push for influential change on campus.

Climate change is a big issue to contemplate, but we don’t have to face it alone. There are many options for anyone hoping to continue this conversation. The CCC is making things happen every Monday at 4 p.m. in Reid, and it is open to any students looking to make a difference.

But that’s not all—Professor Dungy hosts office hours from 2 p.m to 4 p.m. on Tuesdays, and she wants students to know that they are welcome to swing by and chat. The Counseling Center is another resource for students who may feel overwhelmed and can provide students with valuable tools to work through seemingly inescapable climate distress. Seaman ran a climate coping workshop last year, so students interested in more of these events can reach out to her. She also recommends the “Climate Justice, Climate Action” event series. Attending these events is a great way to find a community, open a dialogue and discover ways to take action.

And that’s the heart of it: climate change sucks big time, but there are ways to cope with the pain of it while also making a difference. Get talking, get involved at Whitman and in Walla Walla and get inspired by the endless possibilities for a better future.

And the best part? We don’t have to stop at inspiration, so let’s dig deep and make those possibilities a reality.