Viva la remote revolución: students and faculty wrestle with online learning

September 17, 2020

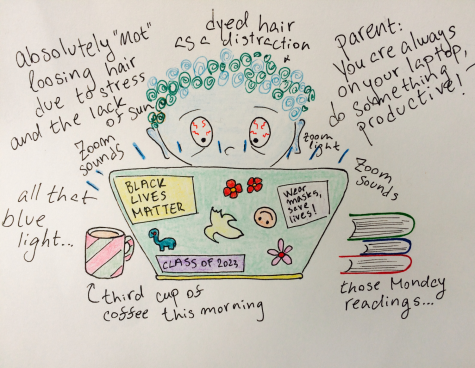

The “business of education,” as Dean of Students Kazi Joshua explained last semester, “must continue,” apocalypse notwithstanding. As we held our collective breath waiting for school to resume, the announcement that classes would continue online came as a disappointment that many were secretly anticipating. A month into the school year, the faces on the Zoom grid grow continually more droopy with each class session. As camera feeds cut out intermittently, I have to guess that my fellow students are engaged in the important work of either bathroom breaks or bong rips. Indeed, the business of education forges on with the blistering speed of progress.

I spoke with several students and faculty to gather their unique perspectives on the current state of affairs. Some offered largely pessimistic perspectives while others maintained more hopeful outlooks, the diversity of their perspectives roughly matching the diversity of their living circumstances.

Iris Cano ‘23 currently lives with her family in Tirana, Albania — nine hours ahead of Pacific Standard Time in Walla Walla.

“The time difference makes it harder,” Cano said.

“Although,” she said, “in a way, it’s easier because it’s more flexible. For one of my classes, we don’t use Zoom. Instead our professor uploads the lectures, so I can watch them whenever I feel like it — which can be helpful, but not necessarily always, because you can’t ask questions — and you don’t feel forced to watch them, because it’s kind of optional … I feel like I have to be more self-disciplined to do all of my assignments.”

Angel Baikakedi ‘24 is an international student from Botswana bound by travel restrictions to stay in the US. She currently lives in the French house with five other first years, two of whom are also international students. This isn’t her first rodeo stateside: She attended boarding school in Vermont, the final trimester of which was taught online.

“Things have been like this since March now so I’ve gotten used to it — and being able to interact with other people does help a lot, especially since we’re living in the same space,” Baikakedi said.

As to the issue of being stuck in the US, Baikakedi is glad to be living in a house with other first years.

“As much as I would be glad to be with my family, I don’t think I’d be able to cope with the time difference. We’re nine hours ahead [in Botswana] … I can’t imagine having to attend my 2:30 p.m. class at 11:30 p.m.” she told me.

Another student, Sage Ali ‘21, lives in Walla Walla but is currently visiting family in Connecticut. She has no class on Fridays, which has allowed her time to drive cross-country without missing class. She feels that, given the circumstances, her professors have been very accommodating.

“In my experience, professors have done a pretty good job adjusting their curriculums to better fit online learning. So, it obviously doesn’t feel the same, and there is a lack of connection that I think is pretty vital to your education experience — but I think they’re doing the best that they can do,” Ali said.

To get an idea of how faculty have adjusted to the changes, I reached out to politics professor Jack Jackson. Professor Jackson’s teaching style relies on prodding students with hypothetical scenarios and expecting them to seriously back up their answers in response. This challenging and provocative style of teaching necessitates a lively and engaging classroom environment.

“Being in a classroom at Whitman allows you to read a mood, to sense experience, to respond to human cues; a dis-embodied Zoom classroom weakens this connection between human beings and replaces it with technological interface. We become more isolated and disconnected (notwithstanding the faux intimacy of beaming in from private places). As well, our capacity to concentrate is weathered by Zoom fatigue,” Jackson said.

Jackson emphasized the unique nature of our moment.

“We are in a biological and political crisis in the United States at the moment, and online learning is an effort to continue education in some format. It is impoverished and unsustainable, but it can perhaps remind us of the value of being together in real space and real time,” he said.

For philosophy professor Tom Davis, Zoom meetings cannot mimic what makes the classroom special.

“There is a good deal of information that can be disseminated through online learning, information that can be manipulated by formulas or protocols that are themselves variations of what an ‘algorithm’ can mean. But no, the so very curious, even enigmatic, event by which all (or at least most) of the bodies in a room collectively go quiet because something important just took place and the room itself wants to know where this importance is going to go next. Well, that event cannot take place in online learning. And thereby neither can this dimension of the humanities as humanities,” Davis said.

Can we really expect a digital “classroom” to match the experience of embodied human beings gathered together in actual space? Let us not be so mindlessly corralled into such thoughts as we stumble onward through this profoundly confused historical moment.