Roo Rat Society

February 15, 2018

For nearly half a century, a peculiar organization garnered 330 members, including three Whitman presidents, and landed itself as news on doorsteps from Ohio to Mexico City, as well as in the heart of a little girl in Florida.

Building off popularity, it wound up in the Encyclopedia of Associations and on the donors list of the Environmental Defense Fund and Save The Redwoods League. Perhaps only rivaled by popular card game Magic: The Gathering, nothing else harbored at Whitman has struck such a chord among many. It takes a trip back in time, along dusty moonlit backroads, to fully understand what Chemistry Professor Jim Todd got into on May 18, 1963.

Biology Professor Arthur Rempel indirectly started the Roo Rat Society. A charismatic professor, he had a large student following especially present in a class that required ten mammals to be found and stuffed.

One day, Todd was asked to drive some students to the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge in southeastern Oregon to gather specimens for Rempel’s class. Todd orientated toward humanely gathering the specimens while causing the least amount of harm to the animal; the students followed. It was there, on that 18th of May, that the Roo Rat Society (RRS) was founded. Todd would later describe the Malheur site as the mother chapter of the society.

The Society

According to its own guiding document, the society is “an organization dedicated to the study and conservation of wildlife and natural resources,” which is the extent to which the society defines itself.

Described from time to time as a “loosely knit organization” and a “soft sell” to conservation, the society has no desire to be anything more than an experience. At the core of its identity, the Roo Rat Society is about visiting chapters, where ‘roo rats are natively found, while accompanied by an existing member, one who has been active in conservation within the past year, to catch and release a kangaroo rat.

“In catching a ‘roo rat it is hoped you’ll become more aware of the living things around you,” said member Dave Harris.

“Many of these people have never touched a wild animal. We are really trying to turn people on in a way they will remember,” Todd added. “[It] plants a seed that may or may not germinate into an awareness of the environment.”

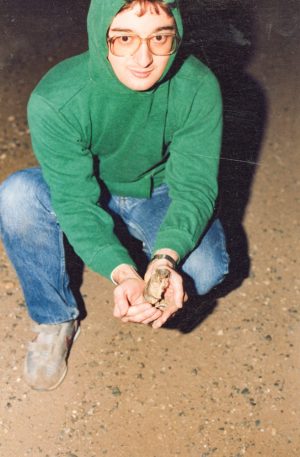

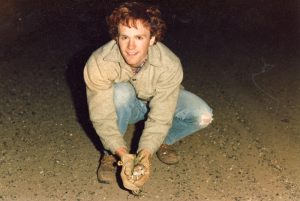

These catch and release expeditions are known as hunts, with the goal being society membership after humanely catching a ‘roo rat.

“It’s not so much a hunt as a Tao-istic turn-on,” Todd said.

Years later, a dispute over this member initiation became a harbinger of the society’s eventual fading out. However, there is one last term to be met in order to remain a member.

The guiding document stipulates that “a member who has participated in at least one conservation project during the past year and/or who is a member of an active conservation organization” is in good standing.

“The Roo Rat Society is not as well-known as Yale’s Skull & Bones Society (George Bush’s club), but it’s a lot more fun,” said an anonymous member.

As to why ‘roo rats versus some other animal, the only answer seems to be that initial trip to Malheur for the specimen collection. Surprising as it was for this conservation organization to be founded on killing animals, the society would not remain this way as it embarked for higher morals by moving away from its unpleasant beginning.

Evolution

Within a year, the Roo Rat Society revised their regulations to prohibit capturing and killing. Todd described it as a necessary evolution as catching a ‘roo represents a contact with nature. Pretty soon, the name caught on around campus.

“It’s not a school club, although we tried [to be one] back earlier, when we were getting organized,” recalled Todd.

However, the administration said no because it “wasn’t serious enough,” he said.

Perhaps this is why Todd emphasizes that the Roo Rat Society is not a Whitman thing; the closest chapter is the Wallula Gap chapter where an overwhelming majority of initiation hunts were held, founded by member Jack Rice.

There is also the mother chapter, as Todd described it, at the Malheur Wildlife Refuge where Todd witnessed his first specimen collection, in addition to a chapter near San Diego, and one near Bruno Dunes State Park in Idaho. Unfortunately, there are not enough members near the ones in California and Idaho; Todd said they should fade away eventually. Unconfirmed chapters are rumored at Carleton College, Pomona College and the University of Washington Medical School. Rules state that one can create a chapter within 50 miles of an existing chapter.

Back at Whitman though, the society kept roaring.

Joining the Roo Rat Society was “the thing to do” for biology and chemistry students, said alumn Meg Stone.

Professor Todd even boasted at one point, “we’re an international organization (members live in Nigeria, Holland, and New Zealand).”

All the while, hunt logs were filling up and lots of students became eager to catch their own ‘roo rat and receive their official Roo Rat Society card.

The real turning point was when journalist Linda Ashton came to town.

Prominence

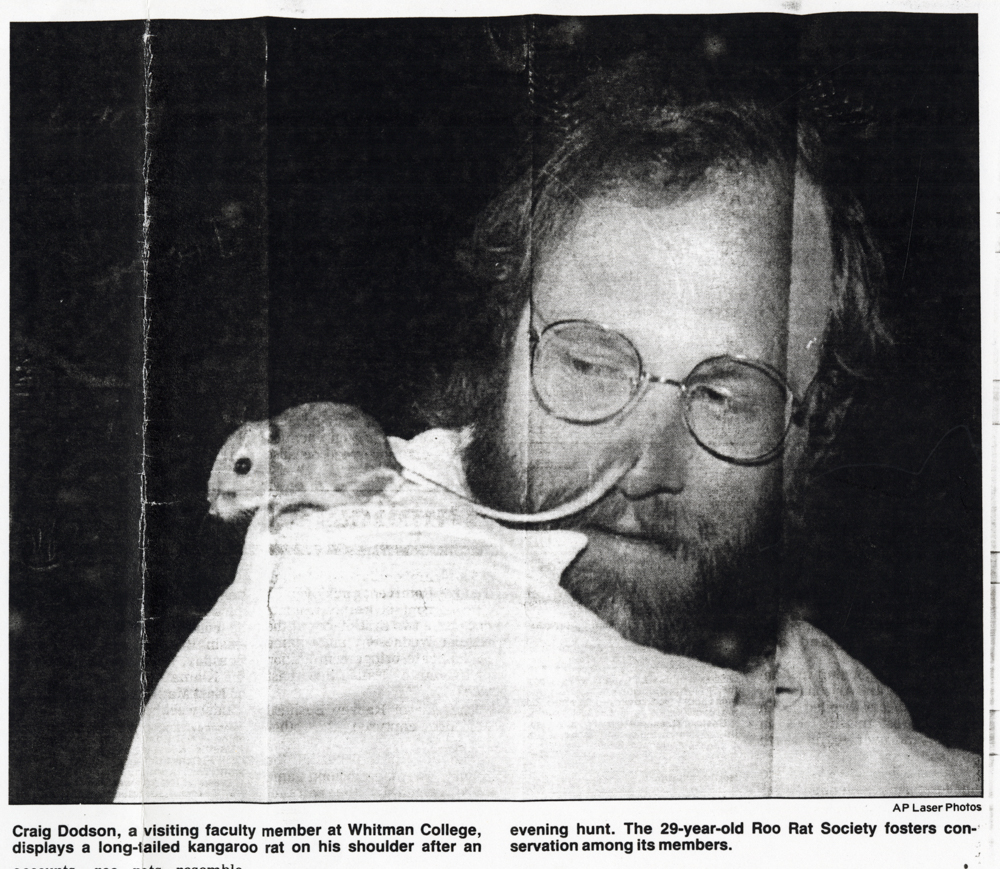

Within its third decade, the Roo Rat Society was in newstands across North America. Letters piled up addressed to the society from impressed readers, all thanks to Ashton and The Associated Press. Local newspapers from California to as far as Mexico City circulated the Roo Rat Society story, fueling the trend.

In the Whitman College archives, there is a note from Oakley E. Woodward who tried to set up a Roo Rat Society chapter in Michigan, only to find that ‘roo rats aren’t native to Michigan. Tom Barnett of Arizona and Dr. D.S. Nelson of California are both interested in joining the society.

The list goes on, but the most heartwarming of letters are from children.

Twelve year old Melissa Wilson of Nebraska asked for information about the Roo Rat Society for an English assignment.

Then there is Marissa Brownlee of Florida, who in 1985 wrote a letter to the society after raising three dollars: “As soon as we reach our goal, $25, we will send it directly to you,” she wrote. “We are all so grateful for your time and effort to help save the endangered species.”

Todd was touched, but turned the money down and encouraged her to join a local conservation organization.

Strangely, not all who wrote to the society were cognizant of what the Roo Rat Society stood for.

“I received a letter from a man in New York who wanted to know how to get rid of the rats in his apartment,” recalled Todd.

The Roo Rat Society also became a listed organization. The Associated Press article landed the society in the comprehensive Encyclopedia of Associations, a reference guide of organizations. They also wound up in the 12th annual Daily Planet Almanac under “Odd Associations.” Similarly, Erica Stux of Ohio wrote an article on strange and unusual organizations, citing the Roo Rat Society.

With a growing awareness came a growing sense of responsibility. The society launched a strong letter writing campaign in opposition to an open-pit copper mine near Glacial Peak by the Kennecott Corporation.

In addition, Doug Blessinger of Twice Told in Walla Walla reported that the Roo Rat Society “has written Congress in support of various conservation movements such as establishing a National Park in northern Washington.”

Professor Todd even exchanged letters with the U.S. Senate Committee on Interior & Insular Affairs Chairman Henry M. Jackson and then acting Chief of the Department of Agriculture Bill Payne. However, the society’s sights were higher as they wrote letters to Secretary of Agriculture Orville Freeman and President Lyndon B. Johnson.

At the micro level, the Roo Rat Society allows members to donate to conservation groups to remain an active member, and the society itself even made donations off of sweatshirt sales, an idea devised by kayaker Rob Lesser. Most of their donations went to the Save The Redwoods League, while others went to the Environmental Defense Fund among other groups.

The Roo Rat Society would continue to appear in various publications by the college as well as other newspapers. It was in this time that the society relished in peaceful membership growth and sticking to the origin of their calling: to get members involved in conservation.

The Golden Age

Deep in the archives, someone wrote on the theory that only one ‘roo allows itself to be caught over and over again, then goes back to spread the word to other kangaroo rats that people are safe. It makes for a nice story, just as the experience of catching ‘roo rats makes for a lifetime memory.

“The best way to see them was right in our headlights as we slowly rolled along the dirt access roads over the hilltop wheatfields,” said Duncan Cox, a society alum.

“Now that I have had more contact with ecology, wild nature, pristine environments, endangered species, the dangers of perching on a moving vehicle, etc., I look back and say ‘What were we thinking?’”said Mary Cocovera, another society alum. “Driving around the desert in the dark on the hood of a car and grabbing those little creatures. The Roo Rat hunt was a highlight of my Whitman years.”

The delight even extended all the way up to Whitman’s presidents, three of which became members. While Dr. Louis Perry and Donald Sheehan have passed, former president David Maxwell definitely remembers his hunts. He recalls the hunt as fun and fascinating; as they drove along dirt back roads in the snowy cold, he began to think they were messing with him as they saw no ‘roo rats. But when the moment came, and he held the little creature, “it just sat there and looked at me,” so cute and docile.

Indeed, many of the hunt logs and memories of members point to the ‘roo rats as peaceful once caught. Getting to that point, however, is another ordeal.

“Roo rats are very fast and hard to corner. Once off the road, a catch is improbable but not impossible,” said member Erick Baer.

As Todd pointed out, catching one is not all fun and games. He recommends wearing gloves as there is a shred of danger if the kangaroo rat is carrying diseases and decides to bite. Once gloves are on, the preferred method to catching is called the two-handed muffle catch. And if you are lucky enough to gently pick one up, you pose for a photograph. Flash on of course, as kangaroo rats are nocturnal. Todd recommends looking the critter up on YouTube if you would like to learn more.

Even with as exciting nights as spotting 55 ‘roos, the glory days of the Roo Rat Society began to twilight. Todd went on to retire, and Professor Bob Carson became more active around the turn of the century. The differences between the two professors began to manifest in a dispute over the induction of new members into the decades old society.

A Fade for Now

The last officially recorded ‘roo rat hunt occurred on October 17, 2006, at The Stateline Wind Farm in Horse Heaven Hills, Washington, with Carson and his wife Clare as leaders. Seven candidates were on the hunt, with five ‘roos sighted and three reportedly caught. This final hunt ended at 10:50 p.m. with the final catch recorded at 10:29 p.m. A sad set of circumstances led to this final catching of the ‘roos.

Carson was a charismatic professor, not unlike Rempel, and led many students out on hunts. He tended to lead larger hunts than usual, sometimes with nine or so candidates.

Carson’s idea was that once one caught a ‘roo rat, they would pass it around and everyone would become a member. Traditionally, the idea was you had to individually corner and catch one yourself, with the only help being someone holding a flashlight. This difference came up at a reunion when Carson tried to convince members that his rule was better. Todd was firm, however, and stood to uphold the regulations of the society set in place since year two or three. This falling out led to the fading out of the Roo Rat Society.

Revival

Last semester, first-year Cam Sipe discovered the existence of this old society through her job in the Alumni Office. The oddity of the society sparked her interest, so she and first-year Chelsea Goldsmith are working to get the society back on its feet. Per regulation, an active member must lead the hunt. They have tracked down the handful of members still around in the Walla Walla area and plan to “start off slow.”

“I am certainly committed to the principles behind the Roo Rat Society,” said Whitman College President Kathy Murray, albeit disinclined to catch a ‘roo rat.

Still, Todd is on board with a revival. However, he has made clear that if the regulations are to be changed, then one should create a different organization.

In the end, Professor Todd believes, “you guys are supposed to be studying. Not wandering around catching ‘roo rats.”

Forward

From 1963 to 2006, the Roo Rat Society became a phenomenon that swept the continent and left a distinct mark on the history of Whitman College. With the memorabilia left behind, and the stories of members carrying their cards around until they fell apart, what is clear after all these years is how profoundly the society impacted those who joined its ranks. Based upon its own criteria, the Roo Rat Society was a complete success. Here’s to hoping it will continue to instill an environmental conscious in the generations of students and conservationists to come.

John Clinton, Esq. Class of '64 • Dec 4, 2018 at 11:35 pm

Long live the ‘roo rat. My “first time” was on that legendary Malheur trip. God bless the ‘roo rat, God’s mightiest creature.

Rob Lesser '67 • Feb 27, 2018 at 4:12 pm

Excellent article. As one who was there in its earliest days, you probably have written the definitive piece about the essence of the RRS. Connecting with nature is always a gift that makes the world a better place. This was our small bridge and it produced many lifelong conservation minded folks. Thanks for putting the Roo Rat Society back on the radar of the Whitman community.

David Maxwell • Feb 21, 2018 at 5:13 pm

Great article about a wonderful group of folks (and equally wonderful little rodents) over the decades. Brings back terrific memories of the midnight hunt in the dunes 🙂