Whitman’s Chess Club

October 20, 2016

The Whitman Chess Club is checkmating the college’s activities scene.

After finessing through a checkerboard of ASWC proposals and speeches, seniors Garrett Atkinson and Matthew Coopersmith’s idea to revive the club, which was inadvertently absorbed into the Walla Walla Chess Club years before, became a reality just last year. Complete with tournaments and computers to analyze matches, the chess club has been revamped into a new and improved, independent Whitman Chess Club.

The club gained official recognition by ASWC the second semester of 2014. Since then, the club has gained ground at Ankeny field for the past year and started up again for its second full academic year this fall.

“When I was thinking about starting a chess club, especially at Whitman,” Atkinson remarked, “I realized that there were so many people interested in it and it just seemed like a really fitting thing to have at a school that’s curious and into fun games like Whitman is.”

In order to become an official club, Atkinson had to garner support. He asked twenty Whitties if they would participate in the club so that he could convey this information during his presentation to the ASWC Senate.

“Either nineteen or all twenty said yes,” Atkinson remarked.

Their first meeting reflected this initial popularity, as they had fifteen members show up.

Since the initial meeting, practices have been held on Ankeny field when weather permits. The club migrates to the Reid basement when the weather isn’t so cooperative. No matter what, practice is held on Saturdays at 2 p.m.

Although chess proves to be popular within the Whitman community, so is everything else. Whitties are notoriously busy with a plethora of activities as well as academic obligations Atkinson states that because people are so busy it is sometimes hard for people to fully commit to the club.

“So many people are interested but you know, as far as actually coming…if you have things to do it makes you feel a little guilty to be like, ‘Oh I’m gonna go play a game for a couple hours,’” Atkinson said.

At the same time, the club’s president Matthew Coopersmith stresses how casual the club is. Members can come to however many meetings they want.

“We’re very casual—we play and laugh and talk. The atmosphere at the Walla Walla club is a little more serious,” Coopersmith chuckled.

Coopersmith added that years ago there was a Whitman Chess Club, yet numbers dwindled as Whitman students started to drift over to the Walla Walla Chess Club.

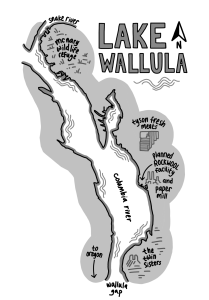

Now the Whitman Chess Club is back on par with their Walla Walla counterpart, even sharing a meeting space. The Walla Walla Chess Club meets in the Reid basement once a month, so this is a perfect opportunity for members of the Whitman community to practice with more seasoned chess players.

Faculty and staff members are invited to all practices as well, although none have shown up yet.

Learning by example is perhaps one of the best methods within the realm of chess. Both Coopersmith and Daniel Bassler, a first-year and recent club initiate, learned to play chess at an early age from their families—Coopersmith at age three and Bassler at age six—and both went on to play competitively–in middle school for Coopersmith and high school for Bassler.

Atkinson began playing at around seven or eight years old and after a brief hiatus was thrust into the world of highly competitive chess within the Seattle Chess Club.

He explained that the club is based off of a rating system determined by the United States Chess Federation (USCF) in which the federation assigns the player a rating based on how he plays versus other players and their ratings.

“With serious chess, there’s a really intense mental energy–when lots of people are playing chess in particular. You can almost feel it, and it’s really exciting to me,” Atkinson said.

The Whitman Chess Club has been amping up its level of competition in the past year, although not to the extreme level of the Seattle Chess Club.

Last year Whitman’s club held a tournament in Maxey Hall in order to send the top five winners to the upcoming University of Washington tournament this year.

Atkinson and Coopersmith said that the format of the tournament in Maxey was Swiss, which means in a match between two players, the winner receives one point and the loser gets nothing; if the result of the match is a draw, each player receives a half of a point. Players worked their way up to the top, until the final five were chosen. It took four to five rounds of playing to get to this point, eliminating players that lost a match and pairing winners with other winners.

Last year, the entire team attended the University of Washington tournament. According to Atkinson, the team attended a lecture and ate breakfast with the UW team while there. The Whitman Chess Club hopes to host the University of Washington team sometime this year. They hope to incorporate activities with UW into the tournament in order to get to know the team on a personal level and form more relationships.

Atkinson finds combining computers with chess particularly interesting. After a match, he inputs his moves into a computer program called Stockfish and reviews his game.

“I get real comfort out of the fact that no matter whatever position you’re in, you can plug it into a computer and they can evaluate the position,” Atkinson said. “They’re just so brilliant. They can think so fast and are so much better than humans at this game now.”

Despite the computer’s extreme skill, it is possible to beat it.

“It’s not perfect,” added Coopersmith.

Coopersmith recalled a video he showed to Atkinson in which a Grandmaster, the highest title a chess player can attain, beat a computer once out of 220 attempts.

“[Atkinson] was so upset the whole day and said, ‘I can’t believe it, I can’t believe it lost,’” Coopersmith said.

Bassler commented that chess computer programs really are ‘superhuman,’ since they encompass the skills and moves of many humans.

“To get a chess computer program going…it’s not really about what the computer knows; it’s about what the programmers know,” Bassler said. “So really the Grandmaster could have been going up against a hundred people working on that program…one against a hundred…so just the fact that you can beat a hundred people all at once is really impressive.”

These godlike programs push humans past their abilities in chess, making people strive higher and higher until they reach the uppermost limits within the world of chess.

In response to the Grandmaster’s one victory, Coopersmith pointed out the ridiculousness in trying to aim higher as a mere human compared to a complex computer.

“Can’t you take pride in the fact that as a human you can win one game? One game out of 220…[that’s] a little victory for humankind,” Coopersmith joked.

This is precisely why Atkinson believes that computer programs bring such a unique perspective to chess.

“The computer stuff to me adds to the fun since you can see [everything] so easily…that part is an extra added dimension of fun,” he said. “It’s kind of cathartic to be done and to be able to review the game.”

Even within an equal playing field of human versus human the game of chess is mind-boggling, which is what makes it so fun.

“[There is a] mind versus mind friendly competition aspect to it that I like,” Coopersmith said.

Atkinson added, “I just find it to be a really fun and exciting game, with a mental challenge for sure…There’s something about it that’s roughly akin to going for a hard, long run…at the end of it you have this really positive feeling.”

Fredric coopersmith • Oct 21, 2016 at 7:46 pm

Great piece. I enjoyed reading this and offer my congrats. Grand pa fredric

Cindy coopersmith • Oct 21, 2016 at 3:50 pm

Bravo for your initiative in getting the club started!

Grandma Cindy coopersmith