Quiet in the Wallowas

Remembering Kip Rand

April 21, 2016

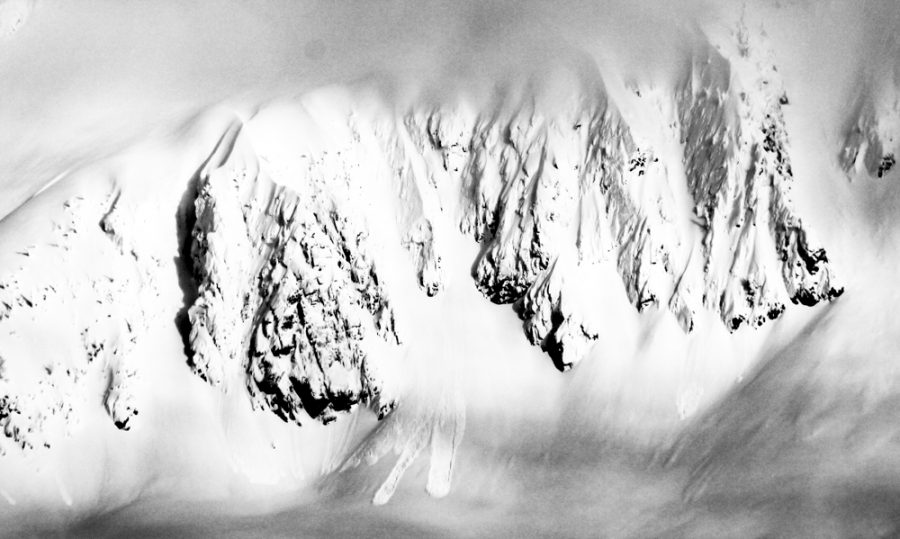

On March 8 of this year, Kip Rand and Ben Vandenbos, friends from their college days at the University of Montana, were backcountry skiing around Chief Joseph Mountain and Sacagawea in the Northern Wallowas. It was an ambitious day. Up and down, up and down. They summited and then skied the north face of Sacagawea peak. Michael Hatch, the lead forecaster of the Wallowa Avalanche Center, of which Kip was the director, believes it might have been the first descent on that route. Such are the Wallowas. Ski a particularly gnarly run and you may well be a pioneer.

Late in the afternoon, they were on the top of Chief Joseph Mountain. The idea was to ski the central couloir, known by locals as the “pencil sharpener.” They treaded carefully. “Everyone,” says Hatch, “knows how big those cornices get on Chief Joseph,” and Kip, who was perhaps better familiar with the 2016 Wallowa Range’s snowpack than any other human on earth, was no exception. They identified what looked to be the smallest part of the cornice, only five or six feet deep on the south side of the couloir – skiers right – and headed that direction. They were about 15 feet back from the side of the cornice. They were an arms-length apart, Vandenbos in front, Kip behind, when the cornice cracked.

Vandenbos jumped back. It had opened between him and Kip. The massive cornice, all five hundred thousand pounds of it – 50 feet across, 20 feet wide, 25 feet deep, released and spun down the chute, taking Kip with it. He tried to self-arrest. He was towards the back of the debris. After around seventy-five feet, Vandenbos lost sight of him.

When he found him, partially buried in snow over 1200 vertical feet below, he was unresponsive. Vandenbos performed CPR and got him breathing. They got off the debris pile to safer terrain. But the trauma was too much. After a few hours, rescue crews still had not arrived, and Kip was dead.

Establishing the Wallowa Avalanche Center

Kip Rand, who was 29, was an instructor on the avalanche course (AVI 1) I took through the Whitman backcountry club last February. The class was from the American Institute of Avalanche Research and Education (AIARE) and the Wallowa Avalanche Center (WAC), and it was a three day crash course in avalanche awareness – red flags, rescue with beacons, snow pits – targeted towards the recreational backcountry adventurer.

This was Kip’s second season as director of the avalanche center. The WAC was founded in 2009 by Keith Stebbings, and Kip was the first paid director. By all accounts, Kip was determined to develop this still-fledgling donor-based organization, one of the few independent avalanche centers in the country, into a civic institution.

Many backcountry adventurers in the region are familiar with The Northwest Avalanche Center (NWAC); it’s an invaluable resource for Cascade adventurers. Every day, new reports come out, specific to a region, and anyone who uses it would attest to its essential value.

Until 2009, the relatively isolated Wallowas had no such resource. The gears were already in motion for the WAC – the impetus was already there – but the avalanche death of Roger Ripka around that time, was a major rallying point.

Julian Pridmore-Brown, who built the WAC website, and who has been the acting director of the WAC since Kip’s death, had taken an AVI 1 course with Ripka. Pridmore-Brown says that prior to Ripka’s accident, there were indications of snowpack instability, but there was no forum to share that information. Ripka’s group had no idea of the observations that other groups had just recently made.

Now Pridmore-Brown is reluctant to draw a clear line between Ripka’s accident and the fact that he did not have access to these other snowpack observations, but still he wonders and laments.

“Maybe they would have evaluated the risks differently, maybe they would have thought about it differently, that was kind of the thought. We wanted to have a way that anybody could go out there and say, ‘hey here’s what I saw, here’s a picture, here’s a video, here’s some information, here’s a snowpack diagram,’ or whatever – any combination of those – and put it in a place where anyone can see it.”

“The basic idea” he says, “is that it’s difficult for somebody just to show up and make a good evaluation of the risks that might be out there without knowing that history.”

Cognitive Biases in the Backcountry

The Whitman backcountry club listserv is full of offers to join some sort of backcountry adventure; most emails request only those that have their AVI 1 certification. Backcountry adventure is not to be done in isolation. You and the mountain and your partners all work together, and it’s important to travel with people who know what they’re doing.

The AVI 1 class was in Joseph, Oregon (where WAC is based), at the base of the Northern Wallowas. It was a mixture of practice in the field and class time in which we learned of different types of avalanches (they are legion), the nature of snow morphology (facets, rounding, rounding facets – self-proclaimed snerds like Kip are in their element) and cognitive biases.

It was the last subject that received an emphasis that surprised me, at least at the time. Perhaps two of the biggest of the course’s takeaways are that avalanches are inherently predictable, and accidents occur not when the red flags aren’t noticed, but when they are not heeded.

“A lot of the time that people get caught in an avalanche situation, there’s reasons that it happened that were much more tied to decision making and human interaction,” said Pridmore-Brown. “It used to be that we emphasized snowpack analysis and digging a snow pit and analyzing the layers … and all that stuff is important from a strictly snow-science standpoint, and you can get a lot of information from it, but for most recreational users, that’s not going to really give them the basis for making a sound decision. The emphasis more now in avalanche education is to clue people into what they should be looking for on a bigger scale … A lot of time parties that are caught in an avalanche … saw other avalanches and yet they continued for whatever reason.”

What might these reasons be? Existing in the nether regions of the human psyche, they can be tough to lay a finger on. It’s easy from the outside, or in retrospect, to dismiss the person who continues despite clear signs that she should not, as a foolish adrenaline junkie or something, but to do so is to ignore the fact that in the same situation, you, owing to your humanness, might very well behave in precisely the same way. Pridmore-Brown, who is an airline pilot (many aviation accidents are a result of similar dynamics) calls it the “human factor.”

“We wanna go out there, and we wanna get that great wilderness experience, and we’ve taken our vacation and planned our life around this one week of skiing adventure, and by god we’re gonna make it happen.’”

Kip Rand the Teacher

It’s worth emphasizing that in the case of Kip Rand, this was not actually an avalanche. Whitman alum and former backcountry club president Tom Whipple has worked mitigating cornice hazards for the public, and he points out that the fifteen foot buffer Kip and Vandenbos gave the cornice is actually a pretty wide berth. Pridmore-Brown’s analogy: it’s “like you’re driving down the road and a tree falls on you.”

Kip was an experienced guide who understood, embraced and proselytized thoughtful risk management. Earlier in the winter he gave a talk on avalanche danger here at Whitman. He was a teacher, essentially. He grew up in Boise, went to school at the University of Montana to study history, but he got in with a particularly outdoorsy group of friends. He enrolled in UM’s Wilderness and Civilization program. Michael Hatch had also done this program, and he regards it as his personal “ah ha” moment. Hatch said that this offered him the opportunity to “meld his love of the outdoors with some kind of formal study.”

Kip, who grew up in the suburbs of Boise, began raft guiding during college. He guided the Salmon River. He guided the Lochsa. It was one of his favorite rivers.

Junior Seana Minuth took the AVI 1 course in 2015, and she remembers hoping that Kip would be the one to lead her tour on the final day, when the class broke off into groups. Her wish came true. She was nervous to break trail for and guide the tour going up the ridge, but Kip eventually encouraged her to the front. Towards the top, a friend in the group dropped her glove and it started rolling down the hill. Kip, quick to action, performed what Minuth terms a “somersault dive” to grab the glove before it was gone. “He was so playful,” she says. “He stood out for sure.”

I was also in Kip’s group on the final day of my course. As we were skinning up the mountain, he tactfully moved the slower people to the front, and when he observed someone who was tired, he stopped the group to give a lesson. Kanye’s “The Life of Pablo,” had just come out, and having not yet been so fortunate to listen, he was eager to hear our thoughts. I told him I was thinking of getting more seriously into outdoor stuff, and he encouraged me onward. A splitboarder skinned by us, and Kip recognized and warmly greeted him. Kip skied like a dancer, whipping rhythmically back and forth with technique clean and tight. He invited us all to hit him up when we came through Joseph in the future.

Embracing the Quiet

Sarah Finger, the budget manager of the backcountry skiing club here at Whitman, says that backcountry skiing is about “being present in the place that you are. It’s just a mental switch that you have to be able to turn on as soon as you step out in the backcountry, because when you’re in bounds you can just whip downhill – yeah you have to be aware of skiers around you and the person taking huge turns on the cat track – but you can pretty much just bomb down without really thinking about where you are. But when you’re in the backcountry you have to be aware of what sounds the snow is making, how the snow feels under your skis, what the trees look like, where the sun is coming from, how the sun is hitting the rocks. You just have to be more quiet inside, so that you can really take in all those things.”

Kip Rand was quiet inside. His energy was kind and straightforward. Harry Sherman, an avid backcountry snowboarder here at Whitman, wrote me that the most memorable aspect of Kip was his “genuine appreciation and zest for life. Watching him in the snow, I could tell there was no other place he would rather be. He was completely present – completely lost in the joy of sharing his passion with others. When he talked about his summer river work, his eyes would light up. It’s a beautiful thing to see someone appreciate life in the way that Kip did, and it continues to be an inspiration to me.”

Kip asked me if I knew Grace Butler, with whom he had chatted extensively during their tour up during last year’s AVI course. Grace is my friend, and when we talked about the accident, she reflected and took solace in the fact that Kip, more than anybody, knew and warmly accepted the risks. In embracing uncertainty, there can be no regret.

Finger says of avalanches and other mountain dangers that “I guess it’s good that there’s something there to keep everyone in check … You have to respect the mountain and respect what’s going on in the snow. It doesn’t matter what sort of fancy airbag you have, or if you have all the most recent gear – you are not better than an avalanche, you can’t outsmart it or outrun it. Maye you get a lucky a few times or one time, but that doesn’t mean you are untouchable.

“What happened to Kip was so,” – she pauses – “so unsettling. But it’s a reminder that you can do everything right, make all the right decisions and still things go wrong. You can be the best driver on the road – be so safe – have a perfect driving record, but some asshole can cut you off and run you off the road. As a skier with your group you are not an independent system.” She pauses again and shakes her head. “It’s so humbling.”