“Things We Didn’t See Coming”

Steven Amsterdam

Pantheon 2009

199 Pages

Visceral in its depiction of a not-so-distant dystopia, “Things We Didn’t See Coming” explores the limits of human relationships: the rare instances that drive us together and all the moments that drive us a part. Amsterdam follows one man through a series of short stories that spans three decades and all physical and societal levels of an apocalyptic world. The Age Book of the Year for 2009, Steven Amsterdam’s debut collection was praised by Harper’s Magazine: “The strength of Amsterdam’s book, as of [Margaret] Atwood’s recent work, lies in its eschewing of pie-in-the-sky theorizing that so often mars science fiction.”

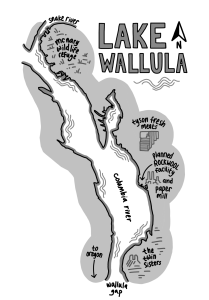

Amsterdam’s future is not composed of handy robots, sleek architecture and hovering cars. No, in fact, any seemingly positive advance in this society’s technology arises out of a need to survive. Trucks become huge and are equipped with televisions and refrigerators because people are forced to live their lives inside them. This post-apocalyptic world is ripe with disease, extreme weather and survival crime, but this is not a story of tremendous fear and isolation (try “The Road”); rather, it is a collection that embraces the connection that is forced, rejected or embraced when vast numbers of people are forced to remain in continuous competition for survival and still attempt to re-create some form of consistent governance.

The collection begins with “What We Know Now,” introducing us to the main character, and unnamed narrator, as a child in 1999 with a father preparing for the impending Y2K crisis. As the narrator grows he makes his way alone in the world, taking varying government jobs (working at barricades, convincing people to leave their homes for dry ground during a never-ending rainstorm) or stealing necessary supplies like water and food. Along the way he meets Margo, who is present through the three center stories as both companion and obstacle: “As long as I have known her, I have never known peace.” Our narrator encounters disease, ego and inefficient government as his life progresses all with the dark backdrop of suffering and constant change, which never seems to be for the better.

Works like this, which string together the life of a character or family through sections or stories, really are the best of both worlds (see Susan Minot’s “Monkeys” for a particularly wonderful example). Each story is self-contained but through the course of the book, a reader can truly gain an emotional attachment to characters as well as revel in their shifting views and opinions. In a way, I would probably have been unable or unwilling to truly accept that Amsterdam’s “I” remained the same character, but this narrator grows and learns as his environment deteriorates and mutates around him in a way that becomes hard to question considering the circumstances. The landscape and the tragedy are both always different in each of Amsterdam’s stories though they all possess the same sense of inevitable strain and disappointment.

Large chunks of time are absent from our narrator’s life, and theses excluded periods seem to be the ones that hold the most important and perhaps consequential moments of his life. What happened to cunning, reckless Margo? How did his family separate and disintegrate? Hints are provided in the lovely, yet abrupt endings of most stories, but it seems that these excluded years might actually hold the best stories of all.

Apocalypse, tragedy, hungry people, desperate people, big trucks and sex are written all over this book, but behind these ideas which are clearly depressing, or made depressing in one story or another, Amsterdam inserts a barrage of humor that feels most right when it is out of place and inappropriate. “Things We Didn’t See Coming” starts out strong, fizzles in the middle but leaves on a commanding note in the final story, “Best Medicine.” Dystopia is never barrels of fun, but Amsterdam creates a world that weighs on you with such absurdity and discomfort that it becomes the kind of baggage you almost hate to see go.