Head to Head: Concussions in Athletics

October 20, 2016

A head to head collision triggers familiar signs: the ringing in the ears, the persistent headache, the nonstop feeling of nausea. If you break a bone, an X-ray confirms it. If you tear an ACL, an MRI confirms it. But if you experience a concussion, no such clear diagnostic test exists. This lack of a diagnostic test has been the central motivator for Professor Thomas Knight and his undergraduate research team at Whitman College in their pursuit of a reliable, fast and definitive concussion test.

Since the fall of 2014, Professor Knight and his team have been studying the affects of concussions on the brain. Concussions—described as mild traumatic brain injuries, or mTBI’s, by the medical community—have recently risen to the forefront of the American consciousness as a major health concern, and over 3.8 million people experience at least one concussion each year in the United States. The goal of Professor Knight and his team’s research is therefore to examine how concussions affect head and eye movements, and use this data to construct a diagnostic test that offers quick results and can be used on the sideline.

Concussions have become a hot topic in the news over the past several years due to increased exposure surrounding the long-term affects of concussions in ex-NFL players and war veterans. Professor Knight notes that public and healthcare “perceptions really started shifting around the mid-2000’s, when reports of former NFL player autopsies revealed pathology, spurring investigations linking concussion and long term disability.”

The problems associated with concussions extend to Whitman’s campus, particularly in varsity athletics. Emma Onstad-Hawes, a senior on the women’s soccer team and one of four Whitman students directly involved in the research, experienced two concussions within a month of each other during her sophomore season. These concussions occurred in relatively close succession, and Onstad-Hawes ended up missing a year and half due to residual symptoms.

“The concussions likely set off a chronic headache and migraine problem for me and I ended up taking a break from sports to figure out how to manage my symptoms and let my brain rest and recover. So, although my actual concussion symptoms likely went away within a few weeks, I’ve been dealing with managing my post-concussive headache problem since I obtained my injuries,” explained Onstad-Hawes. Her story displays a critical component of concussion symptoms and effects. Although one concussion is dangerous, two in close succession can be even more dangerous and sometimes even life threatening since the brain has not been given ample time to heal.

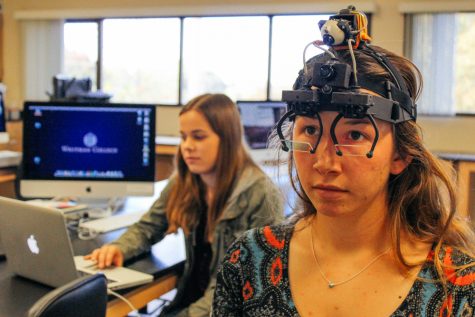

Currently, no definitive diagnostic exists to identify a mild traumatic brain injury, and perhaps even more worrisome, no test exists to determine when it is safe for an athlete to return to play. Because of this, Professor Thomas Knight decided to research if head and eye movements are altered following a concussion, while also examining how long it takes for symptoms to return to basal levels. Professor Knight and 2016 grad Brooke Bessen began work on this question roughly 2 years ago, and used the Whitman varsity women’s soccer team as the subjects of the study. By measuring head and eye movements of women’s soccer payers pre- and post-concussion, Bessen’s preliminary data clearly displayed that concussions resulted in movement deficits overall. After suffering a concussion, subjects experienced slower eye movements, longer reaction times and stutter eye movements when locating a target.

Eye movements have become the central focus of many proposed mTBI diagnostic tests throughout the scientific community. “How the brain controls eye movements is one of the most studied and best understood subjects in neuroscience. The major difference we have is that we’re studying the combination of eye movements and head movements, most of the other studies focus just on eye movements. This means that more brain circuitry is involved and the test is more sensitive because you are demanding more of the brain,” Professor Knight said.

The current research team, which is composed of seniors Katie Foutch, Cassidy Brewin, Tom Howe and Emma Onstad-Hawes, has expanded the study this year to include both the men’s and women’s soccer teams as subjects. Although hockey and football players have the highest rate of concussions, the next highest rate occurs in women’s soccer, which explains why Professor Knight and his team have focused on the Whitman soccer teams.

Concussions, although often mild, can also lead to debilitating effects later in life. In 2002, Bennet Omalu first discovered CTE, or chronic traumatic encephalopathy, in the brain of deceased NFL hall of famer Mike Webster. Omalu’s work set off a wave of critiques surrounding how concussions were being managed in the NFL and ultimately led to the Frontline film “League of Denial” in 2013 and Will Smith’s “Concussion” last year.

“With several former NFL players developing CTE early in life, the public is being shown what some of the worst impacts of concussions look like, which is scary to them,” noted senior varsity soccer player and researcher Cassidy Brewin.

This increased attention, however, has also led to reforms, particularly a concentrated effort to reduce and mitigate the effects of concussions after they have occurred. In 2009, Washington became the first state to protect concussed athletes from returning to play by passing the Zack Lystedt Law, and all 50 states have since then followed suit.

Although concussions do indeed produce a myriad of negative effects, increased awareness and scientific understanding can lead to positive reforms and a safer game for all.

Kevin Earl Wood • Oct 20, 2016 at 11:33 pm

http://baycommunitynews.com/destructive-brain-disease-cte-chronic-traumatic-encephalopathy-now-found-college-football-players-not-just-nfl-florida-officials-particularly-fhsaa-still-refuse-fully-infor/