Recently, music artists like The Weeknd, Rema, and Doja Cat have risen to mainstream fame, captivating audiences worldwide with their distinctive sound, unique artistry, and bold brand images. However, a noticeable trend has emerged – as these artists incorporate more ethnic, cultural, and spiritual themes into their music and personal aesthetics, they face disproportionate backlash to white artists and are unjustly demonized in the media.

Abel Tesfaye initially built his image around dark R&B and emotionally charged music. His work draws on spiritual imagery, dystopian landscapes, and references to somewhat esoteric ideas. Whether through his occasional biblical allusion, his exploration of themes of mortality, or the incorporation of visuals that evoke mysticism, The Weeknd has faced scrutiny. Critics (demonic listeners) have accused him of promoting demonic imagery, particularly after some of his more visually arresting performances, such as his 2021 Super Bowl Halftime show.

The root of the sudden criticism directed at an artist who has always embraced a darker, introspective edge – racism! It becomes more conspicuous when we look at how The Weeknd has openly discussed his Ethiopian heritage in recent months, integrating cultural and spiritual references from his background into his work, such as the churches in Lalibela, Ethiopia during his stage performance in São Paulo, Brazil. Critics are uncomfortable with his unique blending of modern pop with ethnic and spiritual elements. Instead of seeing these as enriching and meaningful, they fall into reactionary narratives, calling them ‘demonic’.

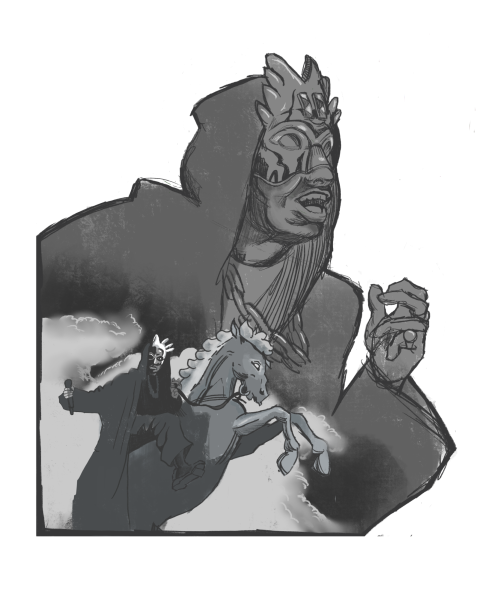

Similarly, growing Nigerian Afrobeat star Rema has been at the center of discussions for his music, which blends traditional African rhythms and spirituality with contemporary sounds. He has started to speak more openly about his Naija heritage and the African influences in his music. Rema’s frequent use of spiritual iconography and tribal art in his visuals has attracted racist critics to accuse him of delving into “occult” or “satanic” themes, a narrative that is often spewed when African artists display any indigenous spiritual beliefs or symbolism.

Then there’s Doja Cat, whose meteoric rise in the music industry has been accompanied by a dramatic shift in her public image. Initially known for her quirky music like “Say So”, Doja has recently embraced a darker, more enigmatic persona, particularly in her recent albums “Scarlet” and “Scarlet 2 CLAUDE”. These albums feature the South African band The Joy and their Zulu samples. The visuals for the “Scarlet” album incorporated spiritual and occult-like imagery and have critics calling her out for promoting “satanic” themes, yet what’s often overlooked is how her artistry has become an exploration of power, identity, and the metaphysical—all wrapped in a broader conversation about cultural spirituality. As a biracial woman with ties to both South African and Jewish heritages, her embrace of this imagery is a reflection of a layered identity, rather than the shallow label ascribed to her because she is a maximalist woman of color.

Demonization rooted in racism isn’t new; it’s part of a long-standing white tradition of vilifying what is culturally unfamiliar. It reflects the continued discomfort with African spirituality and the Orientalist tendency to label non-Western cultural expressions as sinister or evil. Historically, African spirituality, in particular, has been painted as dark and dangerous, a stereotype that persists in pop culture today. Therefore, when artists like Rema or Doja Cat explore their spiritual and ethnic roots, they are subjected to racist cultural censorship disguised as concern about their “message.” The default lens through which much of the West views non-Christian, non-Western spirituality is steeped in ignorance and fear.

This pattern is not only outright racist – it’s hypocritical. Many Western artists have long incorporated Christian imagery, Gothic aesthetics, or esoteric symbolism without facing the same level of backlash. Religious homogeneity is hypocritically circumstantial. From Madonna’s controversial use of Catholic iconography to rock bands like Led Zeppelin weaving occult symbols into their brand, Western spirituality in music has been treated as artistically rebellious and edgy. But when African artists tap into their spiritual and cultural histories, they’re labeled as ‘demonic’.

The demonization of African musicians and their work reflects deeper issues of cultural misunderstanding, religious intolerance, and an unwillingness to engage with perspectives that stray from the dominant Western white narratives. Rather than demonizing these artists like many others for being brave enough to embrace their ethnic and spiritual identities, we should celebrate their art because it pushes the boundaries of mainstream Western culture.