Difficult Conversations Must Welcome Experienced Voices

May 5, 2016

In researching digital journalism practices for my thesis this past year, I came across the work of Cecile Emeke and her ongoing documentary series Strolling. Watching one video, a conversation with Rachell Morillo, I came upon a moment of reflection near the end which has since stuck with me. Having only very recently graduated with a B.A. in Sociology and Anthropology, Rachell thought back on her university experiences and recalled the difficulty she had faced studying issues of race and class as a black girl surrounded by mostly white students.

It was a point which was reiterated at the recent keynote for Immigration Week here at Whitman, and at the Power and Privilege Symposium before that. Indeed, it seems to be something of a running theme throughout our discussions of classroom climate. When talking about race, some progress can be made by working to increase diversity, but things get more complicated when you start looking elsewhere – trans students, for example, will probably always be a significant minority.

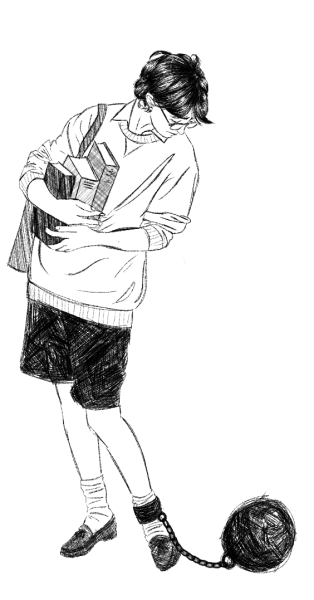

As someone who has been working on a Gender Studies major these past four years, I can testify to the fact that studying race and gender is much harder for those marginalized along precisely those axes. This is to say, the people for whom pursuing a major in something like Sociology, Anthropology, Politics, Gender Studies, or Race and Ethnic Studies is easiest are – you guessed it – cis white men.

This is the case with education in general, but with these fields in particular the stakes have been raised. It is considerably more challenging to be a trans woman in Queer Studies analyzing 1980’s drag culture than it is to be a trans woman in Calculus learning L’Hôpital’s rule. And yet, it is precisely the trans, indigenous, brown, and black voices that we need more of in these discussions on campus.

When the voices most essential to the conversation belong to people who don’t feel safe coming to the table, we need to make the table safer. And while there aren’t any easy answers to this question, I do have two proposals which I think might help.

First, we need to stop conceiving of all opinions as necessarily equally pertinent to the discussion. I understand that this is the exact opposite of the meritocratic “free marketplace of ideas” liberal ideal which colleges like Whitman like to imagine, that we’ve been trained since Encounters to treat a white Christian atheist’s first impressions of a text as “on the level” regardless of social context, but when it comes to issues like race and gender, this policy doesn’t fly. We need to start factoring lived experience into our conversations, and understand that maybe there are other voices in (and outside of) the classroom that matter more than our own. This can happen on the level of course structure – planning time and creating space for students to talk about their own experiences, instead of just the text – but also on a more personal front, recognizing support’s necessary place alongside deconstruction.

Second, we need to understand that, in some instances, asking someone to show up to class ready to discuss issues of racism, sexual violence, or transmisogyny is making their grade contingent upon their willingness to relieve past trauma, and that’s really unhealthy emotional manipulation. The solution to this problem cannot be a dismissive “if the subject matter is traumatic for you, then don’t take the class,” because those voices are important.

It isn’t fair for our classes to hold minorities to the same standards as those who show up every day talking about problems they’ve never had to experience. Again, I understand this spits in the face of the liberal “equal opportunity” fantasy. I believe what I’m looking for is something closer to “affirmative action.” Or maybe, in the case of victims of sexual abuse, “reparations.”

These accommodations will not, in and of themselves, solve our problem, and it is for this reason that conversations happening outside the classroom, like those of the recent Immigration Week or the Power and Privilege Symposium, are so important. But they are a start – and, considering how far we have to go, we need to get started as soon as possible.