During the height of the 2007 troop surge, I engaged in a rather heated discussion with an Iraq War veteran on the topic of the war: its justifications or lack thereof. During the discussion, I held my ground respectably, presenting anti-war chasers to counter his sharp, pro-war cocktail. On one topic, however, my confidence disappeared, and my once independent-thinking mind transmogrified into the ugly beast of blind consent. Perhaps as a baseline from which to judge my worthiness as an interlocutor, he asked me whether I support the troops, and almost immediately I responded, “Of course I support them, no question.” Granted, I probably conceded this so exuberantly as I was quite aware that this guy could drop kick me all the way to Tikrit, yet until now, this has legitimately been my position: highly knee-jerk and never considered critically. It just seemed right to me: regardless of my view on the War, the soldiers should be unflinchingly supported because it’s a dirty job that I wouldn’t want to do.

On hindsight, however, I wish I had responded differently to his question. In today’s political discourse, the question of whether support for American troops should be unconditional and irrespective of one’s stance on the war has become so divisive that people fail to realize that it remains very much a question. Therefore, in writing this week’s column, I hope to look at this question through a critical lens: what does it mean to support the troops unconditionally and is it logically justified?

One way to look at this question is by examining the concept of the soldier, and seeing whether support is implicit in the role he or she performs. Just to get some definitions clear, by “soldier” I mean a member of the military bound by duty to adhere to a given rank in the chain of command, and by “support,” I mean to uphold something as valid or right. If we agree that the military is a necessary component of our government’s executive power, and if we understand that the chain of command is essential in sustaining the military’s effectiveness, then logic requires us to support those who following orders under this chain. In agreeing to this, however, we are not logically bound to support those particular orders; the justification of a given military action as per top policy makers and strategists is very different from the justification for following orders. This is one way in which we can “support the troops but not the war.” The bottom line is that according to this line of reasoning, insofar as a soldier’s role is that of an order-following instrument of the military, not at liberty to determine his or her own course of action, we must support it. This argument has particularly interesting implications because it demands of us to support that aspect of the soldier which is least human, the part which cannot exercise its own free will.

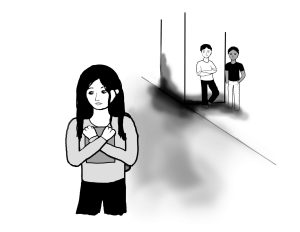

Nevertheless, a soldier is human, and has a free will, as well as a whole slew of rational and irrational components. Our discussion of support for the troops is not complete without considering these factors, and it is through the lens of a soldier’s motivation that personal opinions are relevant and proper battleground for our support. I understand that there are myriad reasons for a person to enlist, such as a perceived lack of alternatives, potential financial benefits, a sense of patriotism and service, hearty desire for a challenge, etc., and support based on these grounds is a different issue. However, considering that military service today is voluntary, if a soldier enlists willingly and out of alignment of principles with the war, his opinions are as open to criticism as anyone else’s are in the public sphere of debate. To illustrate, consider whether a soldier enlisting out of ideological support for the war is any different from a politician running for office on a particular political platform. Both are choosing to enter a branch of the government based on ideological principles, and both actively strive to turn these principles into reality. If I oppose that politician’s political stance, am I obligated to support his campaign? Of course not. Therefore, if I oppose the war, I oppose the ideological foundation upon which a soldier enlists, and I am fully within reason to withhold my support. Therefore, insofar as a soldier is an order-executing appendage of the government, he or she must be supported, but insofar as the soldier is a soldier plus an opinion, the validity of this opinion will determine the level of my support.

Thinking back to that day with a newly-thought stance on the issue, this is what I wish I had said to that soldier: Yes, I do support you for the fact that you chose, as a good citizen and member of a democracy to join the apparatus of government. Democracy requires participation; it requires individuals with opinions, for these are the undeniably necessary components of political discourse. For your contribution to the overall life of our social organism: by taking a stance and acting on it: I support you. But, as to that stance, if I don’t agree with it, I have no obligation to support someone who does, and considering how you chose to voice your opinions: a voice with a characteristic “click” and “boom”: you will simply have to convince me.