On March 26, the Francis Scott Key Bridge in Baltimore, Maryland collapsed after a cargo ship collided with an essential pylon. Six workers who were filling potholes on the bridge were killed in the collapse. The cargo ship in question, the Dali, reportedly lost power before crashing, rendering it uncontrollable.

Assistant Professor of Physics Ashmeet Singh said that the bridge’s construction should not be blamed.

“I think no bridge in the world could have survived a collision like that [undergone by the Baltimore bridge],” Singh said.

Singh further discussed how bridges remain functional.

“The key word when bridges operate is balance, balance, balance,” Singh said. “In any given section [of a bridge], we want the net forces to balance out. So you might have forces of gravity on the bridge; you might have forces of compression … and then you also have tension forces.”

Torque has to be considered and balanced too, Singh added. He explained that creating a balance between all these forces can be difficult.

“Bridges are wonderful, three-dimensional structures. It’s not an academic problem where you have everything in one dimension and forces are easy to balance out. Forces are pointing all over the place … and to [balance them out], you have to be very very precise and very careful as to how things work,” Singh said.

Even though the circumstances of the Francis Scott Key Bridge’s collapse were unique, conversations nationwide have turned towards bridge safety following the incident.

In an emailed statement to The Wire, the Washington Department of Transportation emphasized the safety precautions in place for Washington’s bridges.

“Our agency has a variety of bridges across the state which are regularly inspected and results reported to the Federal Highway Administration. Anytime we have a bridge strike – more commonly an over height vehicle – our specialized bridge crews go out and inspect the bridge and we take whatever steps are needed to make repairs,” the Department said.

Assistant Walla Walla City Engineer Monte Puymon, P.E. explained these inspections in more detail.

“We have a requirement for our National Bridge Inventory (NBI) bridges — which are structures that span more than 20 ft. and carry vehicular traffic … We inspect those every other year, and part of that inspection process provides a sufficiency rating … that gives an overall evaluation of all the structural elements of the bridge,” Puymon said.

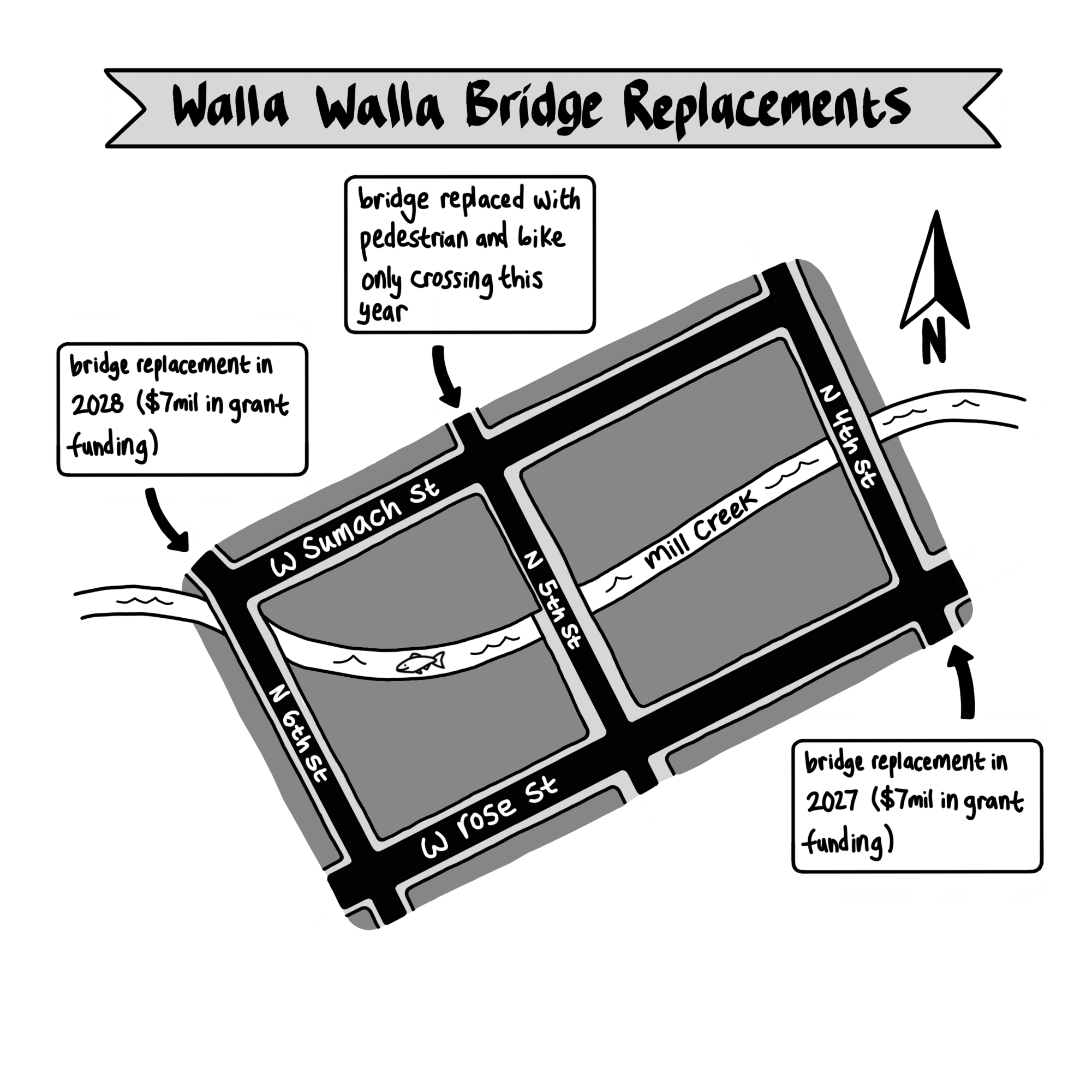

This sufficiency rating, which is a number ranging from 0 to 100, is a major factor in obtaining grant funding according to Puymon. Funds obtained for the coming years include a grant of roughly $14 million for the replacement of 4th and 6th Ave. bridges over Mill Creek, slated for 2027 and 2028 respectively.

Additionally, the 5th Ave. Mill Creek crossing will be replaced this year with a pedestrian and bicycle only bridge.

“These are structurally deficient bridges. Primarily that means that they are load posted/load restricted for heavier vehicles. But another concern that we have with some of our older bridges like these is [that] the railing isn’t designed for vehicular restraint. So if an errant vehicle were to leave the travelway, cross the sidewalk and hit the pedestrian barrier, [that barrier is] not designed for our vehicles of today and that could be a problem,” Puymon said.

The replacement of the 5th Ave. bridge differs from the other two, according to Engineering Project Coordinator Elaine Dawson.

“The reason that between the three the 5th Ave. bridge is being replaced this year is that Tri-State Steelheaders have high priority to improve fish passage in the Mill Creek channel, and the large pier on the 5th Ave. bridge creates an impediment to effective fish passage. Tri-State Steelheaders were able to obtain a grant that covers replacement of the 5th Ave. bridge … and installing fish passage improvements in the channel … between the 6th Ave. bridge and 3rd Ave. bridge,” Dawson said.

Puymon emphasized the importance of grants like these when handling bridge safety.

“Cost plays a big part in when we replace bridges … Just for example, our transportation benefit district, which gets two tenths of a percent of sales tax funds our street improvement program to about the tune of $2 million a year. So if we did nothing for three and a half years we could replace one of those [4th and 6th Ave.] bridges. It’s an extremely expensive process and that’s why we seek the grants,” Puymon said.

Cost has come into play in Baltimore too, with rebuilding costs estimated at at least $400 million, setting off a political debate around labor and funding sources.