Whitman to install turf field despite environmental concerns

May 4, 2023

On March 5, the Associated Students of Whitman College (ASWC) Senate passed a resolution urging the College to conduct an environmental review. Four months earlier, Whitman had announced plans to install a synthetic turf athletic field, a move that stoked environmental and health concerns in a number of students and faculty. Unless a thorough review showed comparable environmental impact between artificial turf and the current natural grass pitch, ASWC would oppose its installation.

Five days later, with no plans to undertake an environmental review, Whitman made the final decision to move forward with the project.

The new field will host Whitman’s varsity soccer and lacrosse teams, as well as a slew of other athletic endeavors, such as club and intramural sports and training camps. Named James K. Hayner Field in honor of the eponymous Whitman trustee, the installation will be made possible by donations totaling $3.6 million. Hayner Field will close out years of effort from Athletic Department administrators.

Still, a number of students and faculty members feel blindsided. Despite Whitman’s long-held plans to upgrade the pitch with artificial turf, the majority of the community was unaware of the possibility until administrators had finalized and announced it. Even members of the soccer and lacrosse teams only heard abstract mention of new turf.

“One of the things I heard from the administration about the artificial turf decision is that this has been a long time coming,” Associate Professor of Sociology Alissa Cordner said. “From talking to some of my advisees who are athletes, they had heard very casual mentions of … someday getting a turf field. From talking to folks outside of athletics, there was no awareness that this was on the table, as far as I can tell.”

Concerned students and faculty cited a number of potential health and environmental impacts. Cordner, who has spent a decade studying per- and polyfluorinated substances (PFAS) and related exposure concerns, was immediately apprehensive: rapidly evolving research points to the presence of PFAS in artificial turf.

PFAS have been colloquially dubbed “forever chemicals” due to their persistence: they don’t break down in the environment nor the human body. Neither absorbed nor excreted, PFAS are bioaccumulative, building up in the body as exposure compounds. Research has linked PFAS exposure to adverse health results, including multiple types of cancer, impairment of the immune system and liver and kidney function. Studies also suggest linkage between prenatal exposure and low birth weight.

The installment of artificial turf could also pose a threat to groundwater and downstream surface water.

“PFAS are extremely persistent in water and extremely mobile in water, so once they get into the water, they’re going to stay there,” Cordner said. “So there are major concerns in terms of PFAS contamination for wherever the runoff from the turf field will go. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has proposed designating two PFAS compounds, PFOA and PFOS, as hazardous substances under CERCLA, which is the Superfund Act. What that means is that the EPA is saying these chemicals are so hazardous that their presence can be used to drive cleanup decisions.”

Cordner shared her findings at a Dec. 9 Trees and Landscaping Committee meeting. Between the initial announcement and the move to finalize plans, the Committee met three times. Attendees discussed the turf’s potential impacts, including toxic water runoff and athlete injury concerns (on which the research is unclear). Proponents of the project, including a coach and several administrators, underscored benefits like decreased maintenance needs and enhanced recruitment potential.

During this meeting, CFO Peter Harvey shared that the turf infill would be made of cork rather than crumb rubber. While students agree that cork is a more sustainable option, it hardly assuages fears. PFAS are found in the carpet layer of turf, or the plastic blades of grass.

In spite of these conversations, Interim ASWC President and TLC member Fraser Moore says that the committee had no power in the administration’s decision.

“The committee was informed of the artificial turf installation plans late in 2022 and was never consulted about the environmental health implications of a field of plastic or the PFAS built into every artificial turf product,” Moore said in an email to The Wire. “Whitman’s administration (President Bolton, Peter Harvey and the athletics department) have not considered the health implications of a field of plastic, nor did they conduct an environmental review to assess the pros and cons of natural grass versus artificial turf.”

The lack of an environmental review and perceived lack of transparency were two main grievances of the students who authored SRS23.2, presented and passed on March 5. Written by first-year Anna Shimkus, senior Eila Chin ‘23, senior Fraser Moore, sophomore Owen Jakel and sophomore Meron Semere, the resolution called for Whitman to adjust its timeline in the interest of community involvement and a full environmental review.

“We had a lot of conversations regarding if we wanted the resolution to be fully against the turf but realized that we didn’t have enough information to make that decision,” Shimkus said. “We realized that the college also perhaps didn’t have enough information to decide if turf was good or bad, given the conflicting benefits and concerns.”

Jakel concurred, sharing: “Environmental health needs to be a priority, and future infrastructure projects should include comprehensive environmental reviews.”

The Sustainability Committee presented SRS23.2 in partial response to a Change.org petition posted by senior McCoy Hennes, a defender on the Men’s Soccer Team. In his petition, Hennes cites the danger of “forever chemicals,” as well as research suggesting higher incidence of ACL injury among female soccer players playing on artificial turf.

In response to claims that Whitman’s current grass field is damaged and unsafe, Hennes pointed to the departure of Whitman’s former groundskeeper, as well as the typical 20-year lifespan of natural grass — Whitman’s field is nearly 22 years old.

This resolution met its firmest opposition from members of the Women’s Lacrosse Team who claim that the current “degraded” grass field puts them at a competitive disadvantage. Whitman’s Lacrosse Team is the only one in the Northwest Conference without a home turf field, and they’ve had to cancel multiple home games this season due to inclement weather.

During the March 3 Senate meeting, several players advocated for the implementation of synthetic turf. One athlete rejected claims that its upkeep would be frequent and expensive: according to Director of Athletics Kim Chandler, the “FIFA-approved” field would last 30 years. Another expressed optimism around reduced water usage, though Moore pointed out that this doesn’t account for water used to produce the plastics that make up turf.

When asked how the administration planned to address ASWC’s demands, President Sarah Bolton shared the following via email to The Wire:

“We worked with an independent consultant and reviewed other studies, including those assessing the safety of planned installations of three FieldTurf fields at Bowdoin College. We were satisfied with the findings and have shared them with those who have expressed concern.”

One of the studies in question is a memo distributed to the city of Portsmouth, New Hampshire.

Whitman is not alone in its current predicament—in fact, similar discussions are taking place at Walla Walla Public Schools. As emerging research demonstrates the impacts of PFAS and their presence in synthetic turf, environmental groups are mobilizing nationwide to prevent turf installation. One such group is based in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, where residents accused FieldTurf (the same manufacturer contracted by Whitman) of dishonesty surrounding PFAS levels in their turf.

In 2020, the city council of Portsmouth voted to move ahead with the installation of a turf field on the condition that it did not contain PFAS. Although FieldTurf representatives assured the community that their products were PFAS-free, later independent testing revealed PFAS in each sample. When environmental advocacy group Non Toxic Dover, New Hampshire moved to pursue legal action against FieldTurf, they found that their contractual definition of PFAS was ambiguous enough to skirt culpability.

In June of 2022, a memo compiled by an environmental consulting firm found that the levels of PFAS in the turf were unlikely to pose severe health risks. When Cordner reached out to President Bolton in November with her concerns, administrators met with her several times, then sent her this memo.

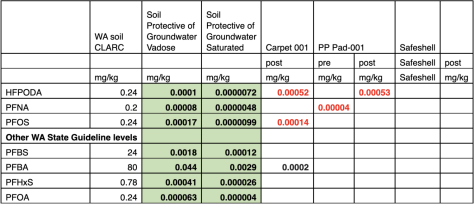

Despite the study’s positive findings, Cordner noted that the reported levels of some PFAS (HFPODA, PNOA and PFOS) still exceeded Washington state screening levels for groundwater protection.

“That doesn’t necessarily mean that Whitman installing a turf field is going to contaminate the groundwater,” Cordner said. “But it suggests that the levels in the turf are high enough that Washington State would say this is cause for concern for groundwater contamination.”

The Portsmouth memo demonstrates a key piece of the turf debate: research on PFAS is young and constantly evolving. As a result, policymakers lack consensus around things like thresholds of toxicity and full range of impact. Environmental advocates — and many Whitman community members — argue that turf’s many unknowns are reason enough to steer clear.

“Once you make a decision like this, it’s gonna be there for a decade — or more,” Hennes said. “That’s where it seems especially important to focus attention into hearing, what is the appropriate decision from an environmental standpoint?”

Hennes bristles at the gap between Whitman’s words and actions. Hennes described an extended land acknowledgment in advance of Matika Wilbur’s talk last month, during which Whitman administrators committed to upholding Indigenous principles of land stewardship.

“To hear that, while also knowing that they’re planning the turf field, potentially without even conducting an environmental review … those are just words if there’s no action,” Hennes said.

Moore finds the move similarly incompatible with Whitman’s purported values, highlighting the impacts on those downstream of Walla Walla. This includes the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation, who source food from the river.

“I believe that this decision exemplifies Whitman’s privilege and continues a history of not considering Whitman’s impact on the Walla Walla Valley and the people that live here,” Moore said. “We do not need to consider the implications of this decision because Whitman will not need to deal with the consequences. What is this if not a colonial attitude to land, resources and people?”

Contractors plan to break ground within the next several weeks.