“There’s my life”: Students on their phones

October 27, 2022

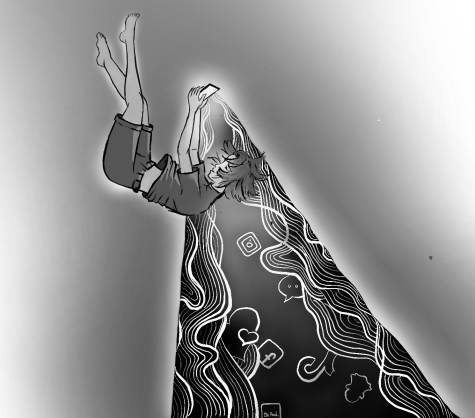

There is something aesthetically unpleasant about walking into a room and seeing everyone staring down at their cell phones.

Senior Cora Patz does not go anywhere without her phone. She reported her screen time over the past week.

“In the last week, I spent 15 hours and 31 minutes on my phone,” Patz said. “Social media [was at] five hours and 14 minutes, and entertainment [was at] three hours and 20 minutes. My daily average is 153 pickups. There’s my life.”

She mentioned that retired philosophy professor Tom Davis would have a lot to say on this matter.

“His whole thing is that we radically disappear and we can’t go anywhere without our phones because we constantly escape into them,” Patz said.

Davis explained via email how phones can enable radical thoughtlessness. He mentioned David Foster Wallace’s essay, “Consider the Lobster,” and described how the uncomfortable feeling of boiling a lobster alive could be eliminated altogether by simply pulling out and disappearing into your phone.

“You do not have to physically leave, because the ‘you’ who feels ‘uncomfortable’ has disappeared,” Davis wrote.

Although Patz rejects the typical baby boomer notion that “your friends on your phone aren’t real,” she admits that there is something missing to the online dynamic.

“There’s no face,” Patz said. “There’s no demand of you to do anything. You’re just acting on your own terms. In a text exchange, you can be like, ‘I’m going to ignore this person for a moment and think about what I’m going to say.’”

She described feeling “icky” about phones being used in social settings, such as restaurants, when the setting is meant to foster interaction.

“The absolute worst thing is when you’re talking to someone, telling them a lovely little story, and they’re just looking at their phone,” Patz said.

Sam Kubishta, a student at Walla Walla Community College who recently started working at the Cleveland Commons cafe, has enjoyed observing Whitman’s atmosphere, including how students wait for their orders.

“Almost everybody uses their phone,” Kubishta said. “When they’re waiting for their drink, they’re definitely going to be on their phone. When they’re sitting down, they’re going to be on their phone or their computer. It’s kind of an extension of them at this point.”

They agreed that staring at your phone could be considered a way to avoid waiting, since it can help you pass the time. Interestingly, though, they noticed that the younger generation seems to be a lot better at waiting for their orders.

“I haven’t really encountered any college students that are like, ‘Hurry up!’ They’re all just, like, ‘It’s okay,’” Kubishta said.

Senior Awadly Elawadly shared that he has started intentionally leaving his phone at home for the sake of productivity.

Meanwhile, junior Grant Didway admitted that he takes his phone everywhere. He is a resident assistant in Anderson Hall, so he checks his phone periodically in case of an emergency. The two of them compared their screen times.

“Yesterday, I had six hours of screen time,” Elawadly said.

“For me, it’s two and a half hours,” Didway said.

Elawadly had opened his phone 66 times the previous day, while Didway had done so 100 times.

“It’s way more than I expected,” Didway said.

Didway finds it strange that whenever he is walking alone or waiting in line for something — like at Cleveland for lunch — he’ll catch himself instinctively pulling out his phone, despite there being nothing to check. At times, he won’t even do anything on his phone.

“It’s scary to realize that you’re kind of incapable of just ‘being’ because it’s not that socially acceptable to not be doing something,” Didway said. “It feels strange to stand in a line and just stare straight ahead.”

Didway describes how there seems to be a social expectation of productivity that affects him when he’s out in public.

“If I’m completely alone in my room and I have absolutely nothing to do, I don’t feel uncomfortable just sitting and being with myself,” he said. “It’s being in public and not doing something that feels strange.”

Elawadly also notices a social stigma against empty time. He noted that whenever friends meet, the question is invariably, “What are you doing?”

“It’s always that when you have to be in a place you have to be doing something,” Elawadly said. “To step outside of my house, or my comfort zone, means that I have something in mind [I have] to do.”

Although phones have claimed an ineluctable place in our lives, Patz and Didway similarly outlined ways in which they avoid its grasp. Patz tries to read before bed, which has recently been a sentence of Plato per night; Didway takes moonlit walks, many times on the path behind Stanton. Perhaps the night’s darkness provides cover from external pressures, freeing everyone from the urge to disappear into their phones.